'I felt constantly attacked': Bullied Montreal teen recounts the toll high school years took on her

Modelling healthy, respectful relationships is key to curbing school violence, says expert

This story is part of School Violence, a CBC News series examining the impact of peer-on-peer violence on students and parents.

Toby Sendel doesn't know why she was bullied, but she knows the toll it took on her.

"It was a hard, traumatic experience that will leave a scar on me for the rest of my life," said Sendel, 18, who recently graduated from Royal Vale School in Montreal's west end.

When she was in high school, Sendel said, a group of "mean girls" would routinely make fun of her, call her names, throw her belongings on the floor and sometimes push her around.

In the school bathrooms, Sendel said, crude notes were scrawled on the walls, calling her a "whore."

"I felt constantly attacked."

At the peak of the bullying, in her third and fourth years of high school, Sendel said, students posted videos to social media, warning her they'd make her life a "living hell" if she showed up for school.

She said she also received death threats.

"I didn't feel safe," said Sendel, who barely went to class.

The bullying made her anxiety problems worse, and Sendel said she spent a good part of her time in the guidance counsellor's office or at home.

"I would try everything not to go to school," said Sendel, who had to repeat Secondary 3 because of her poor attendance record.

CBC survey shows name calling, physical violence common

Sendel said the bullying from other students left her feeling isolated and vulnerable.

She is far from alone.

According to a survey conducted by Mission Research for CBC News, more than half of Quebec students between the ages of 14 and 21 say they were on the receiving end of hateful comments and name-calling in high school.

About a third reported being slapped, kicked or bitten.

One in ten Quebec high school students said they'd been threatened with physical violence involving a weapon.

That scenario played out earlier this month at Alexander Galt Regional High School in Lennoxville, in Quebec's Eastern Townships.

A 15-year-old female student was allegedly threatened at knifepoint by a male student.

Angry with the school administration's response to that incident and others, more than 300 students protested outside the school last week, demanding more be done to stop bullying.

Sherbrooke police have arrested the teenaged suspect. He's expected to appear in youth court Dec. 5.

Collaboration rather than punishment

Compared to the rest of the country, Quebec students actually report fewer incidents of some kinds of intimidation than other Canadians. They report less name-calling, fewer incidents of homophobic or transphobic comments, fewer incidents of being threatened with violence with a weapon, and fewer incidents of theft.

In another study released in 2018, Quebec students reported having observed fewer instances of aggressive behaviour than in 2013 and said they feel safer at school.

Université Laval Prof. Claire Beaumont is the author of that 2018 study, which is based on interviews with 24,000 Quebec students at 84 schools.

Still, Beaumont said, she is not surprised by Mission Research's findings.

Although the Quebec government passed a law in 2012 requiring schools to have an action plan to prevent violence and bullying, there are no requirements set out for schools to follow.

Some are following best practices, Beaumont said, but the approach varies greatly from one school to the next.

"There's still work to do," she said.

Throwing money at the issue will not solve the bullying problem, said Beaumont, nor will doling out punishment to those identified as the bullies.

"If we are kicking students out of school, are we showing them how to behave better?" she asked.

She said suspensions can trigger more frustration and violence from the perpetrators.

She believes schools should focus on modelling healthy, respectful interactions and relationships, as well as constructive ways of resolving conflict — not just among students, but between teachers and students, too.

She thinks some teachers need to change their behaviour.

"There are some who humiliate students, who hand out humiliating punishments, who scream," Beaumont pointed out. "We all need to work in the same direction."

Feeling safe starts with 'respectful environment'

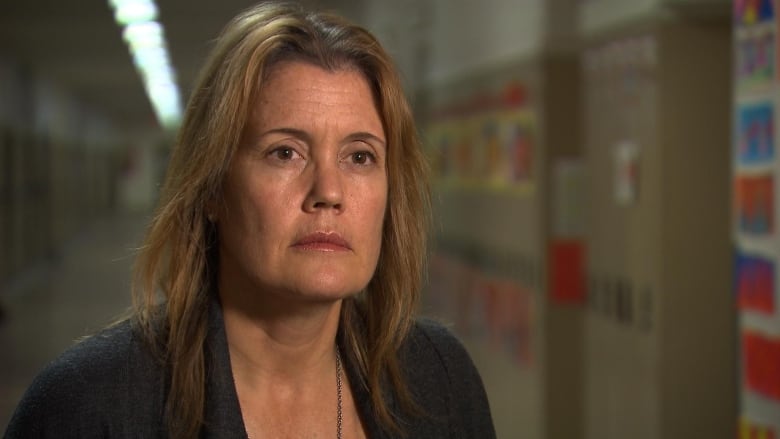

Royal Vale School's principal, Nathalie Lacroix-Maillette, said the school's first responsibility is to make sure all children feel safe.

She believes that starts with having a respectful environment.

When CBC Montreal visited the school this week, the EMSB's violence prevention consultant was giving a teacher workshop on cyberbullying and online exploitation.

The program, called Kids in the Know, was developed by the Canadian Centre for Child Protection.

For students, it talks about how to set boundaries, how to develop the self-confidence to speak up in uncomfortable situations and how to resolve issues in a peaceful way.

Lacroix-Maillette couldn't comment on Sendel's case, as there are criminal charges against one of the people who allegedly bullied Sendel.

But in general, Lacroix-Maillette said, when a bullying incident is reported, the school's administration steps in and tries to resolve it right away.

She understands it is not easy for parents to see their child unhappy, but she said she's very satisfied with how the school has intervened once bullying is reported.

"Our mission is certainly not to please parents at all costs," she said. "It's really to make sure that we have respectful relationships and if there's a case of bullying, it stops right away."

She thinks bullying and intimidation at Royal Vale are under control, she said.

"I am not saying there are no issues — absolutely not," said Lacroix-Maillette. "No school can actually pretend that there are no issues. Whenever we have social interactions, I think it is pretty tricky."

Often, she said some of the worst cases of bullying happen out of sight of teachers and are not reported.

Mission Research's survey shows of the more than 4,000 Canadian youth surveyed, 45 per cent said they did not report what happened to them to school officials.

"In order for us to intervene, we need to be aware," said Lacroix-Maillette.

'It's not you'

Sendel hopes CBC's survey on school violence serves as a wake-up call for schools and students about the consequences of bullying and the fall-out.

She said she still suffers from social anxiety because of what happened to her.

Now at CEGEP, she's happy about school for the first time in years.

Her face breaks into a huge smile when she talks about her classes at the small, private college she attends.

"I'm glad high school is over," Sendel said.

When asked what she thinks schools need to do better to combat bullying, Sendel believes they need to focus on the mental and emotional well-being of their students as much as on the academics.

She'd also like to see more resources made available, both to victims and to bullies.

In her case, she said, some of the people who targeted her were suspended from school, but little changed afterward. She wonders if mediation could have helped get to the root of why they were bullying her in the first place.

"No one is really born mean: they are taught to be mean," said Sendel.

She wants to remind other students who are being bullied that it gets better.

"It's not you. You're not the problem."

Read other stories in this series:

If you have feedback or stories you'd like us to pursue as we continue to probe violence in schools in the coming months, please contact us at schoolviolence@cbc.ca.

With files from Anna Sosnowski