What do the federal parties offer Quebecers in the fight against greenhouse gas emissions?

Here's a look at how the platforms stack up on the key obstacle to lower GHG emissions — gas-guzzling vehicles

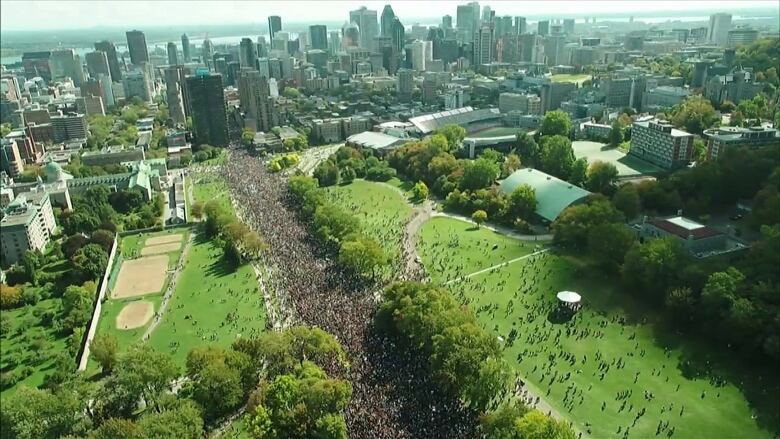

Even before Friday's mammoth climate march in Montreal, polls were suggesting the environment is a key priority for Quebec voters in this campaign.

Voters' awareness of the perils facing the planet have only been heightened, feeding their demand for public policies that have a real impact on global warming.

So what is an environmentally conscious voter to do come election day on Oct. 21?

There are many ways to evaluate the different party promises on the environment. You could, for example, look at where each party stands on carbon pricing or compare their respective conservation proposals.

But unlike some other provinces, the chief source of greenhouse gas emissions in Quebec is transportation. Indeed, it is the only sector of the economy that has seen a significant increase in emissions.

And no surprise: gas-guzzling vehicles are the problem. In 2016, cars accounted for 34 per cent of all transportation emissions in the province; light trucks accounted for 30 per cent and heavy trucks, 36 per cent, according to the Quebec Ministry of the Environment and the Fight Against Climate Change.

So, any serious effort to reduce emissions will have to involve finding greener ways for Quebecers to get around.

OK, so where do the parties stand on electric vehicles?

In its last budget, the Liberal government introduced a $5,000 tax credit on zero-emission vehicles. The NDP has promised to maintain that credit if it is elected.

The Bloc Québécois's platform includes several proposals to expand that tax credit, including boosting it by $1,500 for low-income earners.

"That could allow people who never thought of buying an electric vehicle to say: 'Oh, now it's affordable,'" said the Bloc's leader, Yves-François Blanchet.

The Greens, meanwhile, are promising to ban outright the sale of internal combustion engine passenger vehicles by 2030, while also making electrical vehicles tax-free.

For their part, the Conservatives haven't committed to keeping the electric vehicle tax credit. Their environment platform mentions working with the provinces and industry groups to develop longer-lasting batteries for electric vehicles.

What about public transit?

Another, perhaps simpler, way of reducing vehicle emissions is to get people to drive less. That means increasing mass transit.

"Public transit needs to be at the heart of the climate change debate," said Samuel Pagé-Plouffe, a spokesperson for the Quebec lobby group Transit.

Pagé-Plouffe said Liberal government's creation of a dedicated fund for public transit infrastructure projects helped get several projects in Quebec off the ground, including the extension of the Blue Line in Montreal and the tramway network in Quebec City.

"We're now at historical levels for dedicated funds for public transit at the federal level," Pagé-Plouffe said, though he noted the federal program is complicated for municipalities to navigate.

The NDP has pledged to spend a further $6.5 billion on public transit projects across the country. It's not clear how much would be earmarked for Quebec.

When it comes to more specific proposals, the Greens say they support the Pink Line, a proposed addition to the Montreal Metro system that hasn't interested the provincial government.

The Conservatives have vowed to re-introduce a tax credit — cut by the Liberals — that would reduce the cost of weekly and monthly transit passes by 15 per cent.

Pagé-Plouffe said though that measure would make public transit more affordable, it doesn't address a more pressing problem — the shortage of existing public transit options.

As for the Bloc, there is no mention at all of public transit funding in the party's campaign platform.

What about new roads?

Another way of reducing transport emissions in Quebec entails rethinking what roads are built, and where.

For years, economists have been trying to draw the attention of elected officials to the law of induced demand.

When applied to urban planning, this economic principle holds that building more roads or widening existing roads actually increases congestion.

That's because road construction acts as an incentive for people to take their car, and all that extra pavement gets swamped with traffic just as soon as it is built. So more cars, more congestion and more greenhouse gas emissions.

One way to counteract this effect is by imposing tolls. Another is to simply avoid building unnecessary roads and highways in the first place.

The proposed tunnel between Quebec City and Lévis, which the provincial government is pressing ahead with, has become a battleground for environmental groups trying to make that point.

They argue the link would not only be expensive (estimates range between $4 billion and $10 billion) and serve no discernible need (it connects an area responsible for only one per cent of Quebec City's traffic), but that it would only increase emissions by encouraging more people to drive.

The NDP and the Greens have stated their firm opposition to the tunnel, dubbed the "third link."

The Liberals haven't taken a position on the issue.

Bloc Québécois Leader Yves-François Blanchet, for his part, said he's "not against" the third link.

Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer enthusiastically endorses it. "As prime minister, the third link will be my priority," Scheer said during a visit to Quebec City earlier this week.