In search of the perfect loaf: U of M researchers hone science behind healthier bread that tastes good

Scientists use Canadian Light Source to study how lower salt content influences bread dough and micro-bubbles

The dilemma is this: salt is good for bread, from its impact on taste, to its role as a natural preservative, to the way it stops dough from getting sticky.

But too much salt is bad for humans, and Health Canada says bread products account for the majority of most Canadians' sky-high sodium intake.

That's the problem a team of researchers at the University of Manitoba are attempting to solve, by studying the impact of lowering salt content and searching for a way to make bread that's good for you and tastes good, too.

"It is very challenging, because there (are) lots of players that go into that equation," said Filiz Koksel, an assistant professor at the school's department of Food and Human Nutritional Sciences.

"Every time you change something a little, your whole formula and processing conditions might need to be fine-tuned so that you'll be able to get that perfect loaf of bread every time, in a consistent manner."

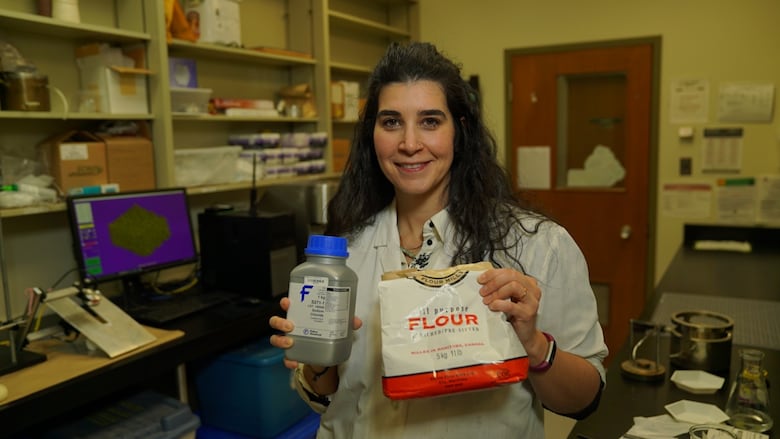

Watch food scientist Filiz Koksel talk bread dough in her lab at the University of Manitoba:

Koksel is part of a research team including Martin Scanlon, dean of the faculty of agricultural and food sciences, and University of Saskatchewan professor Michael Nickerson.

Their most recent report, published in Food Research International, was led by PhD student Xinyang Sun and focused on figuring out how lowered salt content impacts micro-bubbles in bread dough during the mixing process.

"With this type of research, at least [what] we'll do is, when we take a bite from our bread in the morning tomorrow, we'll realize how much science goes into making that, you know, slice of bread … so good and so high-quality," Koksel said.

Bakery products frequent sodium offenders

The average Canadian consumed more than 3,400 mg of sodium daily in 2004, according to Health Canada. That's more than double the daily recommended amount, according to the health agency.

In 2010, federal and provincial health ministers issued a recommendation to Canadians to cut their sodium by about a third, dropping daily consumption to 2,300 mg per day. But a 2017 update from the agency said that didn't happen, and estimated Canadians continue to consume about 2,760 mg per day, on average.

The same report said bakery products, including breads, muffins, cookies and crackers, are the top contributor for sodium intake, accounting for up to 20 per cent of daily consumption.

"While bakery products might look like they're innocent, throughout the day, we consume lots of baked goods and they can add up," said Koksel. "A bread loaf might have only two to three per cent salt, but when you add up the slices, the amount of sodium intake also adds up."

But removing salt from bread isn't as simple as it sounds. Aside from adding flavour to an otherwise bland product, salt plays an important role in improving bread's texture, extending its shelf life and making dough less sticky. A sticky dough means more losses for breadmakers, so businesses have an economic interest in adding the ingredient.

Throughout their study, said Koksel, they learned that how long you mix ingredients plays a crucial role in influencing dough performance, and the best mixing time will change depending on the ratio of salt to water and flour, as well as the various types of wheat cultivars.

Depending on the blend you're using, they identified optimal mixing times ranging from two to four minutes — although that depends on the type of mixer you're using, too, said Koksel.

"What we found that was really important in all of this was from a processing perspective — and this is where bread-making becomes a science and an art — you've got to really be able to know the optimal mixing time to be able to get that perfect loaf of bread."

'Quality is in the heart of the consumer'

Koksel and her colleagues conducted parts of their research at the Canadian Light Source, housed at the University of Saskatchewan. It's the country's only synchrotron, the brightest light in Canada that produces light millions of times brighter than the sun and allows researchers to peer into the interior structure of matter without actually slicing into it.

That ability was crucial for the dough study, because the scientists wanted to study the myriad tiny bubbles inside bread dough that are formed and expand throughout baking. For this study, they focused on the bubbles in the earliest stage of bread making — the initial mixing process, when flour, water and salt are initially combined.

While most North American bread products include yeast, the team left that ingredient out of the mixtures they tested in order to focus more narrowly on salt's impact on bubble production.

"Somebody has characterized bread-making as a series of aeration stages," said U of M food scientist Scanlon. "What we were interested in was to see, alright, in this initial stages when we do the mixing and we change the salt concentration, what happens to that bubble distribution and then how does it change over time?"

Scanlon said the ideal bubble structure varies based on the type of bread and who's baking it. Commercial bread producers may be more focused on consistency, aiming for uniform tiny bubbles throughout the loaf, while artisanal or baguette-style bakers tend to target a wider variety of bubble sizes and distribution.

"Quality is in the heart of the consumer," he said.

The research published in Food Research International is "just a start," Koksel said. The team has already gathered some data on the influence of yeast in dough, and she hopes to see more research documenting the later stages of the manufacturing process, too.

There are a lot of "unanswered questions related to bread, even though it has a history of thousands of years," Koksel said. "We hope to get these answers, one step at a time."