Meth overdose deaths double in Manitoba in 2 years

Methamphetamine linked to 35 deaths in Manitoba last year

CBC News has learned methamphetamine claimed twice as many lives in Manitoba last year as the year before, and the drug is killing more people than fentanyl.

There were 35 meth-related deaths in the province in 2017, say new statistics from the Chief Medical Examiner's Office in Manitoba. In eight of those cases, meth was a direct cause of death, compared to four deaths in the previous year.

- 'It's taken a toll': Medicine walk smudges West End streets in wake of meth crisis

- FEATURE Winnipeg: A city wide awake on crystal meth

In contrast, there were no fatal fentanyl overdoses in 2017 and the drug appeared as a factor in 14 deaths.

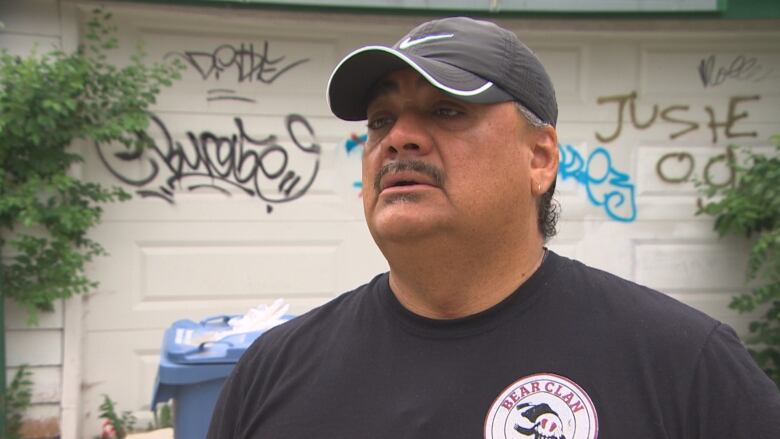

James Favel, leader of the neighbourhood watch group the Bear Clan Patrol, says he is shocked methamphetamine isn't claiming even more lives.

Favel and his street patrol volunteers see the effects of crystal meth use daily. The group spends five nights a week picking up discarded needles off of North End streets.

10 times more needles

Last year, the Bear Clan collected 4,000 needles, and this year they are on track to recover 10 times that. Volunteers have already picked up 30,000 syringes this summer.

"It's an epidemic and it's not just happening here in the North End, it's happening all over the city," Favel said, adding methamphetamine is the drug of choice among intravenous drug users.

"If we're going to recover 40,000 needles, it's incredible how much damage that can do. It needs to stop. We need to address this as the mental health issue that it is."

Crystal meth use has been on the rise in Manitoba in recent years because the drug is cheap, the high is long and it's readily available, police have said.

- Man who died in fall from 15th floor of St. James apartment building took drugs earlier in day, mom says

- 'Community in crisis': Drugs fuelling increase in crime, Winnipeg police chief says

The stimulant is also powerfully addictive and Favel said his patrol members encounter people that are high or in crisis on a daily basis.

Favel pointed to the tragic death of Windy Sinclair, a pregnant mother of four who was found frozen and dead outside days after leaving a Winnipeg emergency room where she was seeking help for her meth addiction.

No antidote or drug replacement therapy

Dr. Joss Reimer, medical officer of health with the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, said the new statistics are not surprising and they are concerning.

"Unfortunately there is no methamphetamine replacement therapy like we have [for] opioids and there's no antidote like we have with naloxone for opioids, so we're very concerned about what we can actually do to help people, to prevent these harms from happening in our communities," she said.

Reimer said she has been hearing from front-line workers in emergency rooms and through harm reduction programs about the dramatic rise in crystal meth use.

The factors that lead to this kind of addiction are complex and it's up to public health and all government services to dig deeper in order to fight what's causing drug use in the first place, she said.

"I think that there is a lot of pain and trauma experienced by communities in Manitoba, some of it having to do with racism or poverty or structural barriers that they don't have access to the things that they need, like recreation and good health care," she said.

"People are just doing what they're doing to get through the day and to try to cope with the feelings that they have."

There is also room to improve resources, including longer-term supports, Reimer said.

"Meth is creating a unique gap, just in that we don't have a place to supervise people while they're high for such a long period [of] time," she said, adding a bed in the emergency room is not always the best option.

"That's something the health-care system really needs to think about and try to come up with solutions."