Indigenous translators vital to language revitalization, access to services, say advocates

Province of Manitoba recently announced funding to train 35 Indigenous language translators over 3 years

The role of Indigenous language translators has changed over the years, but they're still vital to our communities, says a woman who has worked as an interpreter for decades.

Patricia Ningewance, now 70 years old, began translating for Ojibway-language speakers when she was eight. She would work as an interpreter in hospitals, translating for patients who could only speak Ojibway.

In the 1970s, many people in Indigenous communities were translating, she said. That was especially important as many elders at the time did not speak English.

"We were the ones that had to interpret the world for them. That's what we did," said Ningewance, who is originally from Lac Seul First Nation in northwestern Ontario and now lives in Winnipeg, where she teaches at the University of Manitoba.

The province of Manitoba says it's now hoping to increase the number of Indigenous-language translators in the province. It recently announced $300,000 in funding to train 45 speakers and 35 translators over the next three years in the Dakota, Michif, Cree and Ojibway languages.

The partnership with Indigenous Languages of Manitoba Inc. is intended to strengthen the survival of Indigenous languages, the province said in a news release earlier this month.

"Indigenous languages are vital to the survival of the culture and identity of Indigenous peoples," said Indigenous Reconciliation and Northern Relations Minister Alan Lagimodiere in the release.

Ningewance also says that training the new generations to become proficient speakers and translators is important to language preservation.

Her own role as an interpreter has shifted over the years, she says. Now, because there are fewer and fewer monolingual elders, demand for that type of translation work has diminished.

But the need for translators who can help preserve language skills among new learners is still strong, she said.

"I think our new leadership will be the people who are learning the language now. The young people who are becoming parents, and people who are wanting to be the next generation of speakers."

The 2016 federal census — the latest for which language data is currently available — found evidence that more people are learning Indigenous languages as an additional language, according to Statistics Canada. But it also points to the need to train fluent speakers.

That census found that in 2016, 15.6 per cent of the Indigenous population said they could conduct a conversation in an Indigenous language — a drop from 21.4 per cent in 2006.

However, the number of people who said they could speak an Indigenous language increased over that period by 3.1 per cent, suggesting that there were more people who were not native speakers, but were learning those languages as an additional language.

Cameron Adams, who created a Swampy Cree language app, says translators are essential not just to language revitalization, but also to ensuring access to services.

Adams, who is not a fluent Swampy Cree speaker himself, says he's seen situations where interpreters have been valuable.

"What if somebody calls 911 and they only speak Cree? You want to make sure your translators can convey that message so that everyone has equal access to services," said Adams, whose family is from Norway House First Nation and Berens River First Nation.

Translation for essential services is also vital, he says, to ensure people can communicate and get vital information in the language most comfortable to them.

Adams says when documents — such as news articles or government documents — are translated into Indigenous languages, it opens up the language to those who want to learn and see the language used in the same way as English and French.

"That's a value, to make sure that they can have translation in their language."

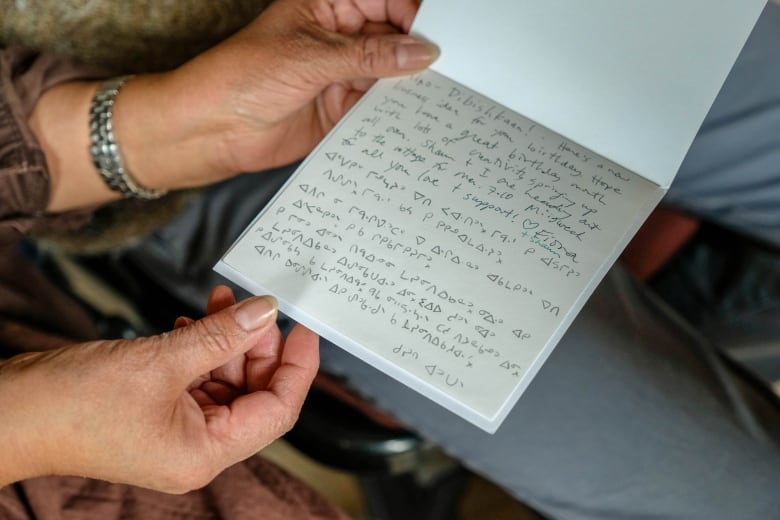

Ningewance says there's a real need for translators who can not only speak Indigenous languages, but read and write them as well. She wants to see less use of phonetic spelling — which isn't standardized and leaves spelling choices up to individual interpreters — and more focus on standard spelling which can be widely used.

"I can think of maybe two people who are really excellent spellers [of Ojibway in Manitoba]. Two people," she said.

She says even when she reads writing from translators who are considered good spellers, she sees a lot of mistakes.

Ningewance, who used to teach an introduction to translation course at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ont., says she would love to teach a similar course here in Manitoba.

"There really has to be good spelling taught."