7 expert takes on why it's hard to define recovery from addiction — and what it means to them

As Manitoba deals with rising meth and opioid use, the question of recovery is more complicated than it seems

Winnipeg is already talking about addiction.

Police say meth is flooding the city. Seizures of the drug rose from roughly 40 incidents in 2012 to more than 480 in 2016. In the first month of 2018, police had already seized nearly half the total confiscated in all of 2017.

The number of people going to Winnipeg hospitals because of methamphetamine rose by 1,200 per cent over the past five years ��— 218 meth-related visits in April 2018 from 12 in April 2013 — according to the city's health authority.

Amid concerns about alcohol and substance use, many families are desperate for more supports, mental health and harm reduction services to help their loved ones recover.

But what recovery actually looks like may be different for different people. Experts, from scientists and researchers to people with lived experiences of addiction, say it's no simple thing to define. Sobriety, relapse, moderation and substitutions — think methadone in place of heroin — are all elements of various takes.

Rick Lees, executive director of Winnipeg's Main Street Project, said at the individual level, people need to define what recovery means for them. But a lack of a working definition can pose problems for policymakers and getting the various groups to work together.

"Nobody's really landed on what that is, and part of the reason — again, from my personal opinion — is that we haven't really clearly defined, what is recovery? What does that look like, how will we know it when we see it?" he said.

"Because I don't think we as a society necessarily spend time talking about, what does recovery look like and what is it — we struggle to create consistent and cohesive plans."

Michael Ellery, clinical psychologist and addictions researcher

Michael Ellery, a clinical psychologist and addictions researcher in Winnipeg, said one of the common misconceptions about recovery is that abstinence is the only acceptable goal. That's not a given, he says, and he begins his work with clients by asking if that's what they want, and if it makes sense for them.

Without a single definition of recovery, he generalizes it like this: decrease impairment, increase quality of life.

With a variety of opinions in the field about how to get there, Ellery said it's important to focus on what's proven to work, whether it's an abstinence-based model, a harm reduction model or something in between.

"There are lots of different scientifically-based things that work," Ellery said. "Things like participation in a mutual aid society [like the 12-step program] ought to be included in that."

Disagreements among people who work on these problems is a good thing, he said: it helps hash out the nature of the beast. They create challenges, though, including making social science and policymaking more difficult.

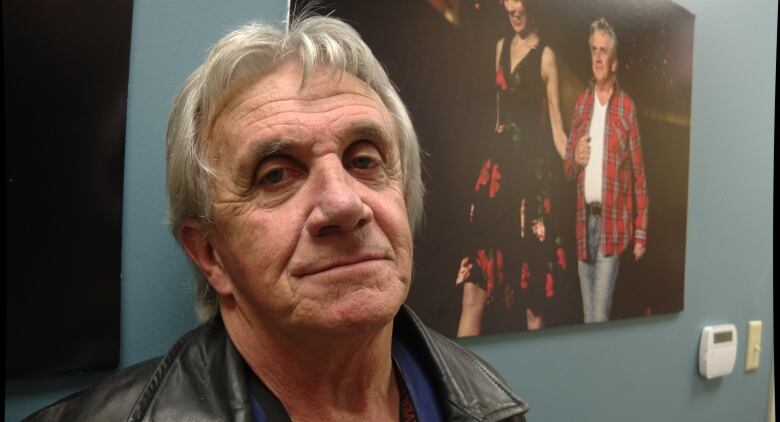

Phil Goss, peer counsellor, sober for 30 years

Phil Goss started drinking when he was 12. In the years that followed, he became addicted to alcohol, then heroin and meth. He didn't stop using until he was close to 40. Now he's about to turn 70 and hasn't used since.

Goss is a peer counsellor at Winnipeg's Main Street Project, a low-barrier shelter, detox and support centre. He says he preaches a harm reduction approach to addressing addiction. But for him personally, it has meant complete abstinence.

"Total abstinence is the only way that I can fly, when it comes to a definition of recovery for me," Goss said. In his experience, slip-ups have sent him spiralling.

But Goss said relapse is part of recovery: it's a learning process. What's more, it's a process that is never complete.

"You're never cured. It can jump up and bite you in a heart beat. [You're] always learning," he said. "It never ends."

A new reality

Lees said recovery is about creating a new reality — not necessarily returning back to whatever life you lived before you started using.

To address addiction, he's more focused on dealing with the side effects and root causes of addiction than sobriety.

"[Recovery] may not include abstinence, but may include balancing the other aspects of a person's life that spin out of control because of the addiction — so that the addiction is no longer the controlling factor."

Lees said he wants people to stop moralizing addiction and focus on treatment.

"At the end of the day, that won't get us anywhere."

Kathleen Keating-Toews, Addictions Foundation of Manitoba

Kathleen Keating-Toews, an education and research specialist at the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba, said recovery happens on a continuum. Abstinence is at one end, but it's not the goal for everyone.

"For one person, recovery could look like completely stopping use, while another person has a goal to use substance in moderation," she said. "At AFM, we look at harm reduction as part of that continuum of recovery."

Instead of a definition of recovery where it's interchangeable with sobriety — that is, removing of a substance from somebody's life — Keating-Toews suggests looking at recovery in terms of what's added in.

"When people are in recovery, they often report improvements to their life areas, such as enhanced self esteem, perhaps improved relationships with their friends and loved ones, better overall health — and that includes their mental and their physical health," she said.

Recovery isn't black and white, and it's not all-or-nothing, she said. Relapses and setbacks are part of the transition, and they can actually help people manage in the long-run.

The concept is hard to define because it's complicated and highly individual, she said, and tends to evoke strong opinion. But however you define it for yourself, she stressed that recovering from addiction is, ultimately, possible.

"Recovery is achievable. But it's not going to look the same to everyone," she said. "We know that even small changes that people make can make a very big difference in people's lives."

Craig Falconer, sober for nearly two months

Craig Falconer started drinking as a teenager, and got into opiods and crack cocaine from there. Now 49, he's been clean for 53 days, thanks in part to help from a 31-day detox at Main Street Project and support from the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba.

For Falconer, recovery means a total lifestyle change: it includes sobriety, but it's more than that, too. For him, it included getting away from some old behaviours and relationships.

"It means being sober, but it also means facing life's challenges when you are sober," he said. "There will be obstacles and disappointments. It's how you handle them."

Falconer said he sees lots of misconceptions about addiction and recovery in the general public.

"They see an addict or an alcoholic and they think they can't change," he said. "I consider it a disease. It's treatable."

But Falconer doesn't think of recovery as something you finish and then move on from.

"It's something you maintain," he said. "You've got to maintain it every day."

Dr. Erin Knight, director of hospital addictions program

Dr. Erin Knight, the medical director of Winnipeg's Health Sciences Centre's addictions program, says she takes a medicalized view of addiction and recovery. Addiction is viewed as a chronic disease, with periods of stability — which some would equate with recovery — and instability or relapse.

"What we're trying to do is provide that ongoing stability, so that relapses can be minimized and people can stay in that recovery for the majority of the time of their life," Knight said.

Total recovery doesn't equate one-to-one with abstinence to Knight. It may include a prescribed substance in place of an illicit one, like substituting methadone or Suboxone in place of heroin.

"On the converse … people who are abstinent from all substances but haven't gotten back a focus on overall wellness and recovery of the important things in their lives, may be abstinent from substances, but aren't truly in a stable, long-term recovery," she said.

For people trying to attain it, Knight said recovery should be defined by the individuals and their goals. But among researchers and policymakers, disagreements about abstinence's role in recovery may be problematic if they prevent access to evidence-based care, like methadone clinics.

Myron Bateman, sober for roughly two months

Myron Bateman, who lived with addiction for roughly a decade from his 20s into his 30s, had been clean for 60 days exactly on Friday. To him, the first definition of recovery he could think of was simple: freedom.

"Recovery to me means success," he said. "Means you won the battle. The nightmare's over."

Bateman had never tried to stop using before he began his two-month streak. On Friday afternoon, he felt confident he was well on his way. He's already planning his next move: starting his own siding and construction business.

Bateman said it's OK that there are a variety of takes on what recovery means. He knows what it means to him.

"I think it just means you're free," he said. "There is a way out."