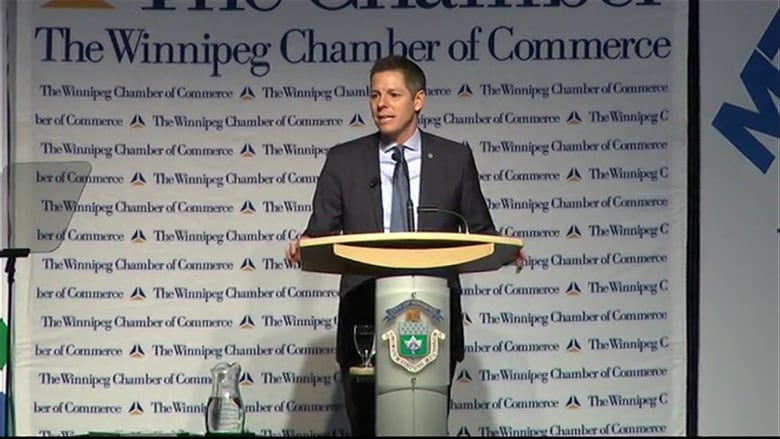

Brian Bowman moving too fast on new Winnipeg growth fees, developers say

Urban planners from outside Manitoba surprised fees on new developments not already in place

Slow down.

That's what developers are saying as Winnipeg Mayor Brian Bowman's crusade to make "growth pay for growth" gains speed.

"Very rushed," said Eric Vogan of Qualico.

Bowman said last week that the city should join other big Canadian cities and start charging developers a growth fee, but he remains committed to keeping property tax increases linked to inflation.

- Winnipeg area will hit 1 million population mark by 2035, report says

- Brian Bowman floats growth fees in State of the City address

That would put the city in a position where it can't expand services to new housing developments without additional revenue.

Vogan said there is a lot of work that needs to be done before Winnipeg starts imposing new fees on developers.

"I would like to see a collaboration of effort from the city and the industry to come up with a good system to make sure that we can finance growth well," Vogan said.

At stake, according to Vogan and the development business, are higher housing costs that will come from what he calls a tax.

"If we find that people are ready to spend $10,000 or $30,000 to buy a house that their neighbour didn't have to pay, then that will be a different story," Vogan said.

Vogan said there hasn't been a face-to-face meeting with the mayor and his staff.

Winnipeg alone not charging growth fees

Bowman does have some support in his quest to put growth fees on new developments, and the claim that Winnipeg stands alone in not charging the fees is correct.

Urban planners from outside the province expressed surprise those charges weren't already levied in Manitoba.

"That's a very unusual situation. Most large cities in Canada have lot levies or development impact charges or development fees," said professor David Gordon, who lectures on planning at Queens University in Kingston, Ont.

He says those new development fees are meant to share the cost of infrastructure fairly and it's perfectly possible to figure out what a fair share is for developers.

Gordon admits in some cases municipalities push the process too far, citing an instance where during rapid growth the City of Mississauga, Ont., used development fees to subsidize the construction of a hockey rink and even part of a new city hall.

But Gordon says if taxpayers in existing neighbourhoods consistently have to pay for new infrastructure "on the edges," it ends up putting "such a strain on city finances eventually cities become anti-growth."

Fees without charter changes tough

University of Winnipeg professor emeritus Christopher Leo agrees it might be the time for a growth fee or levy. He believes growth isn't paying for growth in Winnipeg, adding potholes in older neighbourhoods are an example where the city can't catch up to the infrastructure upgrade areas it has while still adding on new areas.

But Leo also wants to see planning improve and land use tightened.

"Don't pile on unnecessary expenses," Leo said.

He points to opening up large tracts of land in Transcona (Transcona West specifically) and the city's southern region (Waverley West) that need all sorts of infrastructure attention and are on the fringes of the city.

What Leo isn't sure of is how Bowman can get growth fees without changing the City of Winnipeg Charter, which is provincially controlled. Premier Brian Pallister says he won't change the charter and there will be no new taxes under his watch.

"Bowman seems to be suggesting that we recover those other expenses under existing regulations. I find that questionable, let's say," Leo said.

Leo says there is no point in demonizing developers, who are in business to make money. He suspects if there are added requirements placed on new subdivisions and the companies that build them can make a profit, developers are likely to accept those new costs.

Unique charging system

How Winnipeg goes about charging anything on suburban growth is unique. The city uses development agreements with each subdivision, and each agreement is developed on a case-by-case basis, according to a study done out of the University of Toronto in 2012.

It's provincial legislation, not the City of Winnipeg's rules, that form the basis for what's being done currently, and the U of T study called the Manitoba example "the least prescriptive legislation of the five jurisdictions [it] studied."

Growth fees in some form or another occur in all major Canadian cities, but some mayors are hungry to find more ways for their municipalities to recover some of the massive costs of expansion.

Calgary way in front on fees

Calgary is aggressively passing the costs of new infrastructure on to developers. From bridges and interchanges to traffic signals on roads leading into new neighbourhoods, Calgary Mayor Naheed Nenshi has been looking for an end to what he referred to as a subsidy.

Levies were introduced in 2011, but Nenshi felt they didn't go far enough. The city council passed a new round of charges unanimously in 2016, this time to help cover the cost of everything from water and waste treatment plants to libraries, police stations and transit buses.

Those were done, however, after extensive consultation with the development industry.

Bowman says "growth has to pay for growth;" the development industry says added fees to their costs will drive up the price of housing substantially.

The next salvo in this skirmish is expected when a city report on growth fees — and a way to make them without changing provincial rules — comes out at the end of the month.