Female premiers and what's behind their pattern of defeat

Parties in crisis or decline might be more likely to choose women because of stereotypes

Here is a stark fact about Canadian politics: only eight women have ever served as a provincial premier — six of them since 2010. Now, with Kathleen Wynne gone, Rachel Notley is the only one left.

Here's another bit of bleakness: no political party led by a woman has decisively won more than one election.

Rather, of those women who became premier, almost all of them were made premier first through their party's leadership change — taking over from a man while their parties already hold government. By contrast, most men become premier first through a provincial election victory and are then re-elected.

So, what's going on here? And what does it mean for Notley?

The rescue party

Rita Johnston, the first woman to serve as premier in Canadian history, came to power in British Columbia in April 1991. She took over from a beleaguered Bill Vander Zalm of the Social Credit party. But by October, Johnston was out of office — suffering a devastating defeat in the provincial election.

It's a common assumption that women come in to lead parties that are in major trouble and headed off a cliff. And there's a hint of pattern here.

The armchair political theory holds that, as new leaders, these women might be able to eke out another election victory for a panicky party that already holds government but knows it's in serious trouble. Either a crisis, or a decline.

Parties in crisis or decline might be more likely to choose women because of stereotypes. Women are stereotyped as moral, motherly, warm and caring. It's not difficult to see how, if a party is in a mess, some might quickly see that a woman might be the best person to clean it up.

But, the theory goes, after women take the reins, they can't win a second time.

Does this mean that most women premiers in Canada are doomed to fail from the outset?

The short answer is no.

The crisis party

I explore the pattern between provincial party leadership, women and the premier's office in research recently published in the Canadian Journal of Political Science.

In it, I ask two main questions.

First, were any of these parties in full crisis mode when they selected a woman leader?

A party in crisis is one rocked by a scandal or one that has suffered a (series of) considerable electoral defeats. I think two parties chose women because they were in crisis.

The first was the aforementioned B.C. Social Credit when they selected Rita Johnston in 1991, as their scandal centred around former premier Bill Vander Zalm. The second is Pauline Marois and the Parti Québécois in 2007. Though Marois had run to lead the PQ twice before, the party selected her only after it finished third in an election for the first time since the 1980s.

So that's the crisis question. A couple examples, but not a pattern.

The second question: Were any of these parties in decline when they selected a woman as leader?

The fading party

A party in decline would see its support fade over time, so it's more challenging to see in any one instance.

You have to look for a party losing votes, losing byelections, with falling public support and getting fewer donations. The idea is that if a party is in a downward spiral, a party might look to a woman to change the channel and clean up the mess.

But, and this is really important, if these parties are selecting women because they are in decline, we must see that decline before women were selected to lead. When you look at the data, there's also just no clear pattern for this argument.

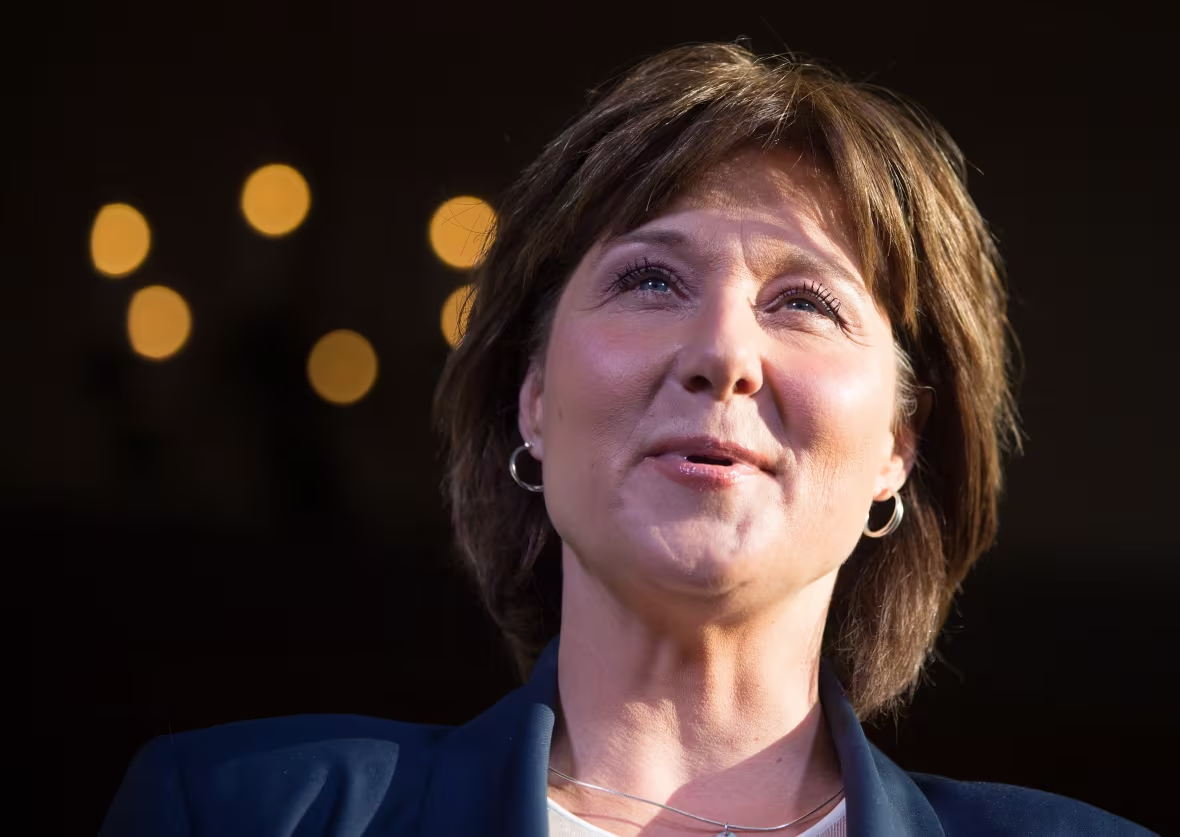

Only the Ontario Liberals were in documented decline when the party selected a woman leader in Kathleen Wynne. There's just no clear pattern for any of the others, including Catherine Callbeck (P.E.I., 1993), Kathy Dunderdale (Newfoundland and Labrador, 2010), Christy Clark (B.C., 2011), and Alison Redford (Alberta, 2011), despite their later negative trajectories.

OK, so, if there is no pattern to be found in this group, no deficit in female leadership, no evidence that the party would have "gone down" no matter who led, why do female premiers seem destined to a single term?

Let's look at a couple things that can happen.

First, a new female premier can come in and succeed in cleaning up the party mess. This could then draw more men out of the woodwork who want the top job, now that it's more desirable, and challenge her. Second, party insiders might grow cool on her or seek to punish her, either through a lack of any real backing or by actively pushing her out before she wants to resign. Third, the issues might be greater than any one leader could mitigate, and the party heads into an electoral defeat.

These are all different potential causes for a single term defeat — not a pattern in themselves. But these quick exits are the one nearly universal pattern for women premiers.

Most women in politics encounter sexism that produces double standards, ensuring they still walk a rougher road as premier than do men. It's clear that's a major contributor to women's shorter tenure as competitive party leaders.

So, what does this mean for Rachel Notley?

Sexism, economics and a unified opposition

Notley's path to the premier's office was closer to that of a man than of the other seven women who have served as premiers before her.

She first won her party's leadership, then she led her party to a majority election victory. In that sense, her path to party leadership was both very different (from the women) and also somewhat unremarkable (because it's just like the men's).

But Notley has faced serious challenges most premiers don't.

Most premiers don't take over at the start of a recession, nor do they have to try to lead their provinces out of one.

Conservatives in Alberta have been fighting each other since 2008. While Notley's NDP certainly needed some Wildrose vote splitting to help "toss the rascals out" in 2015, the polls now clearly show that support has gone back to the UCP fold.

Economics and a united right present Notley a challenge, but there are also the things she faces that male premiers don't. Things that are a threat to her re-election. Things that form a pattern. Things like misogynistic threats.

While everyone in politics experiences some biting criticism from the public, Rachel Notley is the only premier in Alberta that I know who's been threatened with her own funeral arrangement.

That such threats against her spiked around the centenary of some women getting the right to vote in Alberta shows how sexism menaces women premiers in ways most men cannot imagine.

Defeating the 'pattern party'

We have a long way to go before the next provincial election. But, given the current context, many would bet against Notley winning in 2019. Given that a re-election pattern of defeat has happened to every other woman who has served as premier, it should give us pause.

Before 2010, political scientists claimed that the premier's office was more hostile to women than most other political positions. Now, nearly 10 years later, I'm not yet convinced much has changed.

Certainly, Alison Redford in 2012, Christy Clark in 2013 and Kathleen Wynne in 2014 were all anticipated to lead their parties to major defeats. That they didn't speaks both to their political skills and to the vagaries of electoral politics. But re-election is a different matter.

Honestly, we haven't seen enough women-led competitive parties to know exactly how many voters view them through a sexist lens, and then use that at the ballot box. Despite this, women clearly have the skills to lead their parties to unexpected landslide victories.

The difficulty is that, for what I think remain sexist reasons, parties do not choose women to lead them when they appear to be on the brink of a fresh mandate in government. Instead, they seem to be more likely to call on women to be the "nurturing fixer in a time of trouble." Party leadership in these times of trouble is less attractive, in part because the party could easily lose anyway (leading many men to just not want the job). So, while there may be correlation with electoral loss and a woman as premier, there is no causation.

To suggest so feeds the stereotype that women don't have the skills to lead parties to electoral victories, when the reality is that many of these women have succeeded against really stiff odds.

This column is an opinion. For more information about our commentary section, please read this editor's blog and our FAQ.

Calgary: The Road Ahead is CBC Calgary's special focus on our city as it passes through the crucible of the downturn: the challenges we face, and the possible solutions as we explore what kind of Calgary we want to create. Have an idea? Email us at calgarytheroadahead@cbc.ca.