Century-old treaty stops Alberta farmers from using Milk River for much of the summer

Head of local council calls the river ‘water with a Montana license plate’

The Milk River looks great right now, according to farmer Elise Walker.

It's high, it's flowing and it's fairly clean.

For now, she and about 30 to 40 other families in southern Alberta can continue using the water to irrigate their farms, helping to get them through a very dry spring. In fact, Walker already started to irrigate her 607 hectares (1,500 acres) of land at the end of March — the earliest ever.

But she and other farmers are steeling themselves for that moment in the near future when they'll have to watch the water flow by.

"Last year we were caught off guard being shut off on July 9th," said Walker on the Calgary Eyeopener. Her ranch is about three kilometres east of the Milk River.

"I don't think we've ever been shut off that early … It's very stressful."

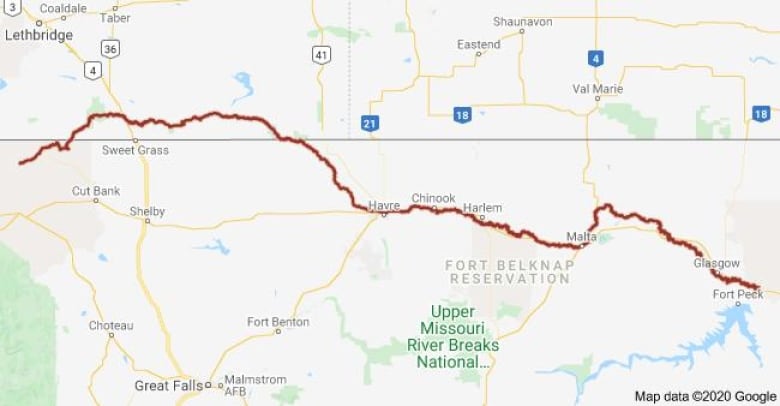

Use of the Milk River is restricted by the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909. It was signed to help resolve disputes over the use of waters shared by Canada and the United States, such as the Milk River, which runs through both Alberta and Montana.

The St. Mary's diversion dam in Montana pushes water through the Milk River, which then travels northeast through Alberta, and then back southeast through the U.S. About 80 to 90 per cent of the Milk River's flow comes from that diversion.

Executive director of Milk River Watershed Council Canada Tim Romanow calls it "water with a Montana license plate."

"It's Montana water that they're entitled to … and it'll support their irrigators, but it'll have to go and flow right past the Canadian irrigators," he said.

Canada is allotted a certain amount of the river's natural flow to be used for their own irrigation, but once that's up, it's hands-off.

Already this year, Alberta Environment and Parks put out a warning.

"Current conditions and predictions indicate that consumptive use by irrigators in Canada will likely exceed Canada's share of the natural flow in the Milk River," it said in an April 29 email.

If that happens, it'll be the fourth time in six years there isn't enough water for a full season of irrigation, Walker said. That'll impact the hay, barley, corn and grass seed on her property, as well as her cow-calf operation.

"We can't continue like this. It's not economical. It's crippling the families and the neighbours in our area."

'It's just been tough'

The extent of the problem largely depends on mother nature, said Romanow.

"The snowpack is actually excellent in the upper St Mary's. It's above average for this time of year," he said.

"The problem is that the way the treaty is set up for the way the water is shared, we can't benefit from that on the Milk system because it's largely a prairie river that's reliant on spring melt and spring flows."

Climate change is playing a role, Romanow said. He doesn't think the flow volumes have changed much, but the timing and duration are not the same anymore.

Adapting to those changes is crucial in order to keep Alberta farmers in business.

"It's very important to our community because it allows us to produce enough of our own feed and forage, … allows these large cow-calf operators to be sustainable," Romanow said.

The system is managed by the International Joint Commission (IJC), which is composed of officials from both Canada and the U.S.

It launched a study in November to look at ways to improve water access and long-term resiliency for both countries. Those results are expected back in about four years.

Until then, Alberta Environment and Parks says it will be working on their own ways to help farmers.

In a statement, a spokesperson said the ministry will work with stakeholders "so Alberta is well prepared for the possibility of more significant and extended water shortages and drought in the future."

The government expects to receive its next update on Milk River conditions May 25.

It's all little comfort to Walker, who for now — along with other farmers — is making tough decisions on how to get through the season.

"It's stressful. This year, we tried to get out there and seed early, changed up our agronomic practices … seeded something different because we know we're going to get shut off early," she said.

"It's just been tough."

With files from Nathan Godfrey