The complexity and the urgency behind calls to defund the Calgary police

Behind the heated rhetoric there is nuance and monumental challenges, but also broad consensus

It is hard to keep track of the wave of stories sweeping over North America, of police checking on someone struggling with mental health, only to leave them dead or battered. Of Black and Indigenous people beaten or killed by armed officers, often equipped with the latest in tactical gear.

And in the aftermath of each death, each beating, the placards rise, demanding the police be defunded. The slogan hits hard. For those accustomed to the idea of police as protector, it is astonishing, unthinkable. To those for whom the police are a threat, it is obvious.

Behind the simple slogan, however, is a complex argument that goes to the heart of systemic racism in Canada and beyond, and to the heart of how we treat people, based not only on race, but class and mental health. It is a dense mixture of forces that divides society into its silos.

To dismantle the portion of that system that is the police would require concrete actions involving different levels of government, but also the willingness of society to confront its perceptions of fear and safety, and to reverse centuries of bias and belief in the power of punishment.

Untangling that web requires first and foremost delving beyond the surface arguments of social media and the polarized rhetoric to understand just what's meant by defunding the police and how that might play out in Calgary.

It is perhaps less controversial than it appears.

What is defunding?

There is a spectrum of views when it comes to what defunding the police actually means. For some, it is about abolishing police services as we know them.

For others, it is a conversation about how to move money from bulging police budgets into other organizations and services, removing responsibilities like mental health checks from police and focusing more on crime prevention and poverty reduction, funding legal aid and ensuring Black, Indigenous and people of colour are represented in a meaningful way in police services and beyond.

It's about looking holistically at a system that is failing too many.

In Calgary, it's that latter conversation that appears to be the focus of attention, with a petition by Calgary Supports Black Lives Matter calling on city council to reduce the budget of the Calgary Police Service and put that money toward community-building initiatives, mental health services, transit and more.

There are reasons for those calls.

The big picture in Calgary

The Calgary Police Service is the single biggest line item in the city's budget, gobbling up over $400 million each year. It's a big dollar figure, and yet the specifics of the budget and the needs assessment it is based on remains opaque, even to those in the know.

Jyoti Gondek is the councillor for Ward 3 and sits on the police commission, the civilian oversight body for the service. She says that, after two years on the commission, she still has questions about what money is going where.

It's a transparency problem she says goes beyond the police, with city departments panicking when council starts asking to take a closer look at their budgets.

"The thing that I struggle with the city budget is we don't have that level of detail on many things and we've been asking for it for a while," she says.

"And I know, as a new member of council, I find it really frustrating when we say things like, you know, it's a three per cent increase to the base. Well, what's in the base?"

That's an important question when it comes to police budgets.

Historically, in Calgary and beyond, police will arrive at council with requests and dire warnings about the safety of citizens in the face of any cuts. And despite the fact there was a small reduction midway through 2019 to the police budget, Calgary police tend to see funding requests met.

That happens because, despite a lack of specifics, the police service can play to citizen hopes and fears in a way that parks or recreation could never do. Trimming a summer camp is not only more politically palatable to councillors, it also doesn't raise the anxiety of Calgarians who, according to the city's citizen satisfaction survey, want more police on the streets.

But that experience doesn't ring true for many Calgarians.

"I see cops here all the time," says LJ Parker, a Black Lives Matter activist who started the petition to defund the Calgary police, of her northeast community.

"And like I mentioned in the petition, I saw that armoured vehicle parked out by the church, like a block away from my house. I was like, what is this doing here in the middle of the day?"

Parker, like Gondek, wants to see a more detailed breakdown of just where police are spending money and why they feel it's necessary, including that armoured vehicle.

Her fear of a heavy police presence, in contrast to so many others who are afraid of a lack of police, is grounded in the reality of this city.

Killings, interactions and arrests

A database compiled by CBC News in 2017 showed the majority of people killed by the Calgary Police Service — at least 84 per cent of the 19 people killed between 2000 and 2018 — were mentally ill and/or had addictions issues.

That number was almost 15 per cent higher than Canada-wide figures.

Calgary also had the most police shootings of any city across Canada in 2016 and came close to earning that title again in 2018, when officers shot nine people, killing five — shootings that were not included in the CBC News tally.

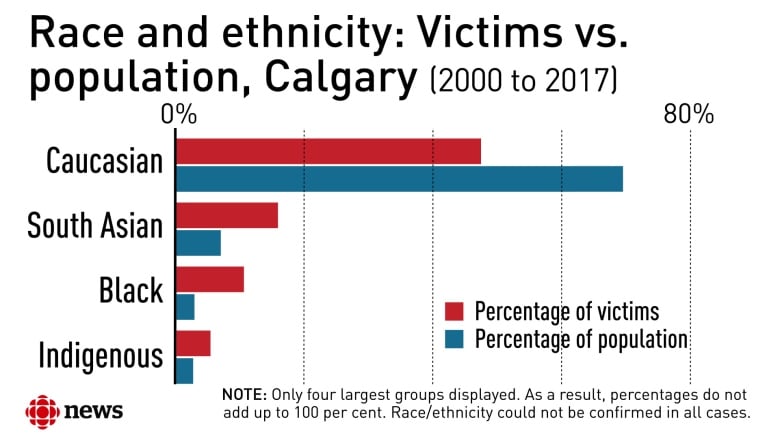

Black, Indigenous and South Asian Calgarians were overrepresented as victims of fatal police shootings, about double their share of the population as a whole.

Statistics collected by the Calgary Police Service also show Black, Indigenous and people of colour are overrepresented in interactions with police, relative to their share of Calgary's overall population, and federal statistics show overrepresentation in the country's prisons.

When taken together, these statistics, along with allegations of bullying and harassment within the Calgary police, indicate that something needs to give, that change is required and defunding to refocus priorities might be one way to achieve that.

But saying so on social media, or writing it on a placard is one thing. Confronting the systems of support and punishment that chug along within the vast municipal, provincial and federal bureaucracies is another.

The nuts and bolts

Coun. Gondek agrees things need to change, and says she's open to having the conversation about shifting police resources elsewhere, but it's clear the thought of moving through that process is overwhelming.

For one, the province would have to be at the table so there could be collaboration on shifting attention for mental health calls away from police and toward support services.

Calgary has no purview over mental health, she says, so if the city takes away funding from the police for that, what assurances does the city have that mental health services will be provided?

"I want to know that it's actually going to get done, but I don't actually have a right to that," says Gondek.

Something as large as the police service can't just change its service delivery model overnight and can't risk leaving gaps in the system.

There are also the politics and the tough-on-crime approach that sells so well to so many. There are divisions on council, there are police unions, and a citizenry in Calgary that widely supports increasing the police budget, rather than slashing it.

There is also racism — unconscious or otherwise — embedded in organizations that don't have people with lived experiences to fill in cultural and racial blind spots.

"The one thing I always say is representation, representation, representation," says Spirit River Striped Wolf, the president of the Mount Royal University Student Union.

"And not just one single Indigenous voice either, but, rather, meaningful representation. I always say it has to be to a point where Indigenous folks can hire other Indigenous folks where, you know, Black folks are able to hire other Black folks, and so forth. And not just having one single Indigenous or Black voice to be that placeholder."

A spokesperson for Alberta's justice minister says the province is reviewing the Police Act and has met with "chiefs of police, Indigenous leaders, the chiefs of Alberta's Indigenous police forces, minority community leaders, mayors and councils and will continue meeting with a wide range of stakeholders" as part of that process.

The statement says Alberta has seen a "dramatic" increase in rural crime and the distribution of drugs like fentanyl.

"Lastly, I will point out that this government has made historic investments for mental health and addiction treatment," reads the email from Jonah Mozeson.

He pointed to $140 million for mental health and addiction and $53 million for supports during the pandemic that make it easier to access services from anywhere in the province.

Shifting perception and understanding

Striped Wolf argues society has gone too far in separating police from social work and other disciplines, focusing police training in one direction. But when officers head out into the streets, they are asked to do that social work anyway.

"I think we see that with the recent murders of Indigenous people, specifically when it comes to mental health, I just don't think that there's enough training there," says Striped Wolf.

"And, you know, there is something to say when folks feel endangered because of someone's mental health condition, but we have to think of better, innovative solutions than just murdering them point blank."

There are issues of trauma to resolve. There are issues of trust to resolve and there are broader perceptions about humanity that will continue to stifle change.

Michael Bates has been a defence attorney in Calgary for years and sees the same issues debated over and over, and politicians rising to power on promises to fix a broken system. What's more, he says, everyone in the justice system, broadly speaking, is working toward the same end: ending the cycle of crime by addressing the issues that give rise to it.

But still, not much changes.

"There's risks out there and there's things that scare us," Bates says.

"But the more reasonable we can be in the approach to people who are in crisis, or people who are having difficulties or problems, and approach them as a person and not as a problem.... It allows us to, I think, get past the idea that we need constant police protection."

Bates — perhaps selfishly, he says — would like to see more money spent on legal aid, so that those who deal directly with people caught up in the justice system have the resources they need to prevent that person from being caught up in it again.

The problem, in short, is big and complex, and when you dive below the surface, overwhelming. But there appears to be broad consensus that change is needed.

The consensus

From the chief of police to politicians to activists, almost everyone agrees that the force is doing too much and moving into areas best served by social services and those trained to help.

Officers feel overworked, and stretched thin.

In short, everyone is sort of on the same page.

There is already work being done in the city to try to decriminalize situations and remove the need for police — a visible example of which are the DOAP Teams that patrol downtown and respond to calls for those in need of shelter and detox.

There are partnerships with other organizations that focus on crime prevention and providing resources to at-risk youth. There are drug courts that work to help people struggling with addiction, rather than punishing them.

And yet despite that consensus, there is concern that change will not come quickly enough.

The trickle, the urgency

Inertia is, quite literally, a force of nature, and it takes on a whole new meaning when society and its supporting bureaucracy are at play.

But Black and Indigenous activists point to the changes made to combat COVID-19 as proof that big, complex issues can be tackled quickly if there is urgency and the political will to do so.

"I think a lot of folks are going to say that, like, 'Oh, this is a big topic and we need time and so forth. But I think people of color, and Black and Indigenous people are very familiar with that. And we know that once you wait for something, it doesn't end up happening," says Striped Wolf.

The self-preservation of the system and of budgets and careers and the status quo is coming face to face with the self-preservation of people, and it's still not clear which side will win.

But there is hope.

Politicians are talking about it. Activists are organizing in new ways. The police are acknowledging the systemic racism that exists in their organizations, and there is a public will to push forward with reforms that will prevent scenes of police kneeling on throats, or tackling Indigenous leaders, or shooting those experiencing a mental health collapse.

"It feels so overwhelming. It feels very, very big," says Gondek.

"But you know what? We as a society abolished slavery, we as a society made a decision that a woman has a right to her body. We gave women and Aboriginal people and people of colour the vote. So if not us, then who?"