Nearly 40 million rapid COVID tests unused in Alberta as expiry dates loom

Alberta Health says unused tests will be discarded after they expire

Alberta has close to 40 million COVID-19 rapid antigen tests in its stockpile and they're all set to expire within a few months. Those that go unused will be trashed, the provincial government has confirmed.

According to the province, of the 6.7 million kits stashed in a central warehouse, 760,000 expire on Jan. 1 and the rest will expire by March.

Each kit contains between five and 25 tests for a total of 39,621,105 individual tests.

"From my understanding, these test kits are from the original batch that was purchased originally, a couple of years ago and we're just kind of going through them still," said Randy Howden, president of the Alberta Pharmacists' Association.

"At some point, those kits probably will need to be disposed of. I can't imagine them working too far past their expiry dates. But, of course, we do need more information on that."

According to Alberta Health, the free test kits, supplied by the federal government, will be discarded once they expire, following guidelines for the disposal of medical waste.

The stockpile of rapid antigen tests, which are stored and distributed from a centralized Alberta Health Services' warehouse, are still available to pharmacies, continuing care homes and primary care providers.

While the province did not provide further details on the disposal of the test kits, it said pharmacies have been reminded there is stock available.

"That's a lot of landfills full of tests," said Dr. Lynora Saxinger, an infectious diseases specialist with the University of Alberta.

She'd like to see further analysis done to determine if the tests could be used beyond their expiry date. Saxinger said older tests may be less sensitive. The biggest concern would be false negatives, rather than false positives, she noted.

"Unless more information comes forward about whether the tests perform reasonably — like they're revalidated after the expiry date — I can see why maybe they wouldn't want to give them out anymore," she said.

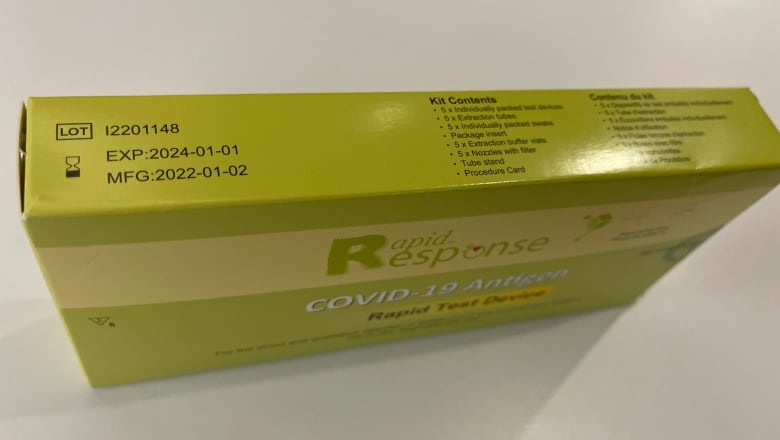

BTNX Inc., one of the key manufacturers, said Rapid Response boxes with a reference code listed on the box as COV-19C25 have a standard shelf life of 24 months (from the manufacturing date) and should not be used beyond the expiry date stamped on the box.

These kits make up a significant proportion of Alberta's stockpile.

The company was authorized to extend the expiry dates on other batches of tests. Those have a reference code listed on the box as COV-19CSHC5.

The province did not confirm prior to publication time if any of these are in circulation in Alberta. The extended expiry dates range from March 2024 until June 2024.

Meanwhile, Health Canada does not recommend using expired rapid antigen tests.

It said companies do "extensive research," including gathering data on how components function over a period of time and under changing conditions such as extreme temperatures.

"The authorized shelf life is the amount of time for which the company has provided scientific evidence to support the conclusion that the product will continue to perform as intended," a spokesperson said in an emailed statement.

"Results of an expired test may not always be accurate. It is recommended that people use unexpired tests and follow the provided instructions carefully."

At Wellness Pharmacy in northwest Calgary, pharmacist Muhammad Ashraf said he has approximately 100 kits left in stock, all of which expire in January.

"I'm pretty sure before they expire I will run out."

He's only ordering them as his stock is depleted because customers are no longer stockpiling the tests like they did earlier in the pandemic.

Instead, he said, they're picking up kits as they need them.

"They want to test right away.… People who come have a symptom and they're feeling they need to be tested and they want to test their family, too."

Meanwhile, some Albertans are finding lower levels of buffer fluid in their test kits.

"That would be the one thing that would probably be a weak point in the test," Saxinger said.

She noted that, while it's not ideal, if people are doing a rapid test and find they don't have enough buffer fluid, they could add a drop or two from another vial in their kit.

"If it's negative, I wouldn't necessarily trust it. If it's positive, I would definitely trust it," Saxinger said.

"I think people should still pick up the available tests and have them ready to use, just recognizing if they use it past the expiry date, they might need to get followup testing if its negative."

Saxinger is worried many people have stopped testing when they're symptomatic. It's still important, she said, especially as the respiratory virus season kicks into high gear.

"I do think people have kind of lost track that there still is value in doing the testing and that it can help you make better choices," she said.

"You should be more cautious about spreading that because there still are people who are getting very ill with this. There's still people getting admitted to hospital, ICU, and dying with this."