'We were at this tipping point': APEC protests at UBC continue to shape politics 20 years later

Lawyers Craig Jones and Joel Bakan say APEC was the first in a chain of anti-globalization protests

Craig Jones wasn't planning on protesting that day.

Jones was a 32-year-old University of British Columbia law student at the time of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit on campus 20 years ago today.

"I was a pretty straight-laced, middle-of-the-road kind of law student," said Jones, now a law professor at Thompson Rivers University.

Nor did he expect to later find himself pinned under a pile of police officers, under arrest for championing free speech.

"I remember it all pretty vividly," he said. "It became a pivotal or defining moment in my life."

The APEC conference had summoned world leaders from across the Pacific Rim to discuss trade partnerships and economic development.

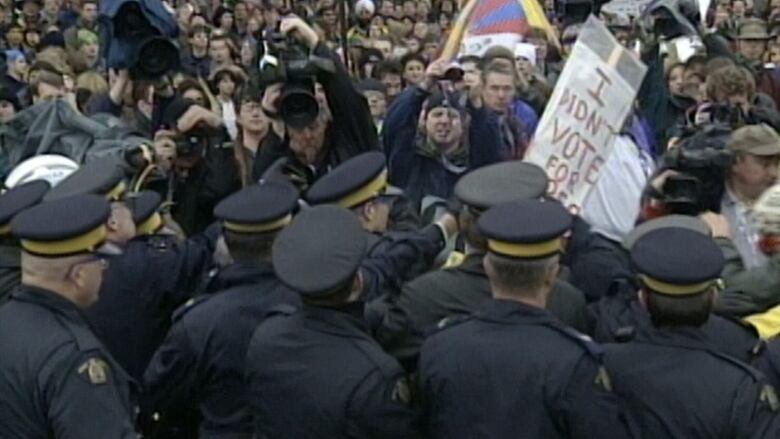

They were greeted by thousands of protesters rallying against what was then seen as the rise of neo-liberalism and the fall of democratic institutions — many were arrested and pepper sprayed.

The demonstrators said globalization would perpetuate human rights abuses in countries with low wages, all while stripping workers in the West of good-paying jobs.

Today, many acknowledge the APEC protests as the birth of the anti-globalization movement that swept the late 1990s and early 2000s with repercussions that continue today.

Twenty years later, similar rhetoric rooted in inequality, democracy and social justice has worked its way into the mainstream politics of elected officials like Senator Bernie Sanders, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio and Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante.

Pepper sprayed at short range

Images of police blasting protesters with pepper spray and arresting them for civil disobedience that day captured national newscasts.

Dozens of media covered a subsequent years-long inquiry into how police handled the situation, and the role of then-prime minister Jean Chretien.

Chretien was accused of pushing for police to quell the protests so former Indonesian president Hajji Suharto, known for human rights violations in his country, could save face.

Many Canadians found the allegations disturbing, seeing them as a violation of civil liberties and free speech.

Jones was one of several who testified at the inquiry.

Leading up to the protests, he had found it troubling that the normally picturesque campus resembled an armed warzone, complete with snipers on rooftops.

Even more worrisome was the fact that police had arrested protest leaders like student and anarchist activist Jaggi Singh in advance of the summit, telling them not to come back to campus.

"We thought well, at the very least we should protest the crackdown," Jones said.

Jones put up signs advocating free speech and democracy. Their placement along the motorcade route for world leaders was what landed him in trouble with police.

"When I was lying on the ground with three police officers on my back, I thought, 'I am in deep shit here,'" he said.

Jones describes the APEC protests as a "watershed" in Canadian history that influenced police response to future anti-globalization protests in Canada.

He says police took note of public reaction to their actions and the subsequent inquiry.

APEC a tipping point

Joel Bakan, a UBC law professor and author of The Corporation, which analyzes the modern-day behavior of corporations, was also on campus that day.

Bakan says APEC was "the first in a chain of anti-globalization protests" led by concerns about neo-liberalism and the expanding power of corporations — to the detriment of civil, Indigenous and human rights.

"There was this sense that we were at this tipping point where democratic governments were in effect losing control of these major transnational and multinational corporations," he said.

The next of the big conferences came at the 1999 WTO Conference, nicknamed the "Battle in Seattle." Similar protests followed at the 2001 Summit of the Americas in Quebec City and the G8 Summit in Calgary in 2002.

Eventually those major protests drew fewer protesters, and many said the anti-globalization movement had petered out.

But Bakan says they just morphed into other forms: the Occupy movement that began in 2011, and today as social justice movements focused more specifically on issues like inequality, climate change and housing.

Bakan now sees those issues playing out in mainstream politics, especially at the municipal level in cities like New York and Montreal.

"It was really the beginning right here in Vancouver of a recognition in today's contemporary world of economic injustice and economic power and issues that need to be reckoned with in order to ... enable democracy to flourish," he said.