Pride, apprehension marks 20th anniversary of historic B.C. First Nations treaty

'If the Nisga'a nation can't make it, then modern day treaty making is going to be a failed experiment'

Twenty years ago this week, Joseph Gosnell sat in the same chair in his home that he sits in today, waiting for a phone call with the results of an historic vote.

Gosnell, now 82, was the chief negotiator for the Nisga'a Nation, whose territory sits midway up British Columbia's wild West Coast. The Nisga'a were voting on whether to accept a ground-breaking treaty with the provincial and federal governments that was decades in the making.

"It's one of those events in the history of our nation that, to me, was extremely important," Gosnell said.

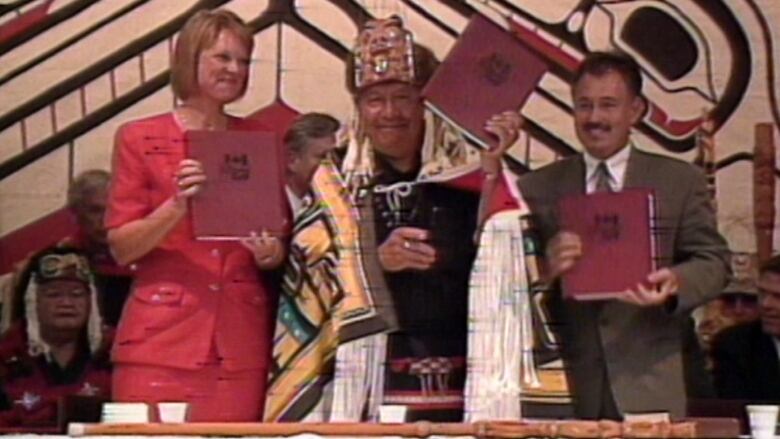

The Nisga'a voted in favour of the treaty — the first signed agreement in the province's ongoing modern treaty process. Unlike other provinces in Canada, most of the First Nations in B.C. never signed treaties or surrendered their traditional territories.

The agreement still had to go through the House of Commons and the Senate, which took another two years.

It gave them land title to about 2,000 square kilometres and paid nearly $200 million in compensation. It also gave them the right to govern themselves and no longer be under the jurisdiction of the Indian Act. The Nisga'a could form their own government, run their own health services and schools.

It was a controversial treaty that many, including some Nisga'a, disagreed with. Some said the Nisga'a had given up too much for too little.

Twenty years later, some Nisga'a speak with pride about their right to self-govern. However, they also speak of the many challenges that come with that responsibility after decades of not having their own institutions in place.

Some Nisga'a, like Joseph Gosnell's niece, Ginger Gosnell, say the lack of jobs and industry puts the nation's longterm viability at risk.

Tourism could be an answer, but she says there isn't enough infrastructure like hotels and restaurants to attract people to the remote area. And energy projects like an LNG pipeline are hotly contested.

"I think we probably have a best-before date in front of us where we're either going to make it or we're going to break it," Ginger Gosnell said.

"I think if the Nisga'a nation can't make it, then modern day treaty making is going to be a failed experiment."

'The ability is there'

As soon as the Nisga'a vote went through, Joseph Gosnell's phone was flooded with calls from people who wanted to know when the new Nisga'a government would be in place.

Today, Joseph Gosnell still likes to sit in the Nisga'a legislature to see the nation's leaders govern.

He's proud of what the Nisga'a government has accomplished, but decades of disenfranchisement leave room for improvement. Many leaders have no prior governing experience and have not attended post-secondary institutions, he says.

"But the ability is there, I know the ability to govern is there. And to me still improving today," he said.

Lack of revenues

His niece Ginger Gosnell, 40, says the nation's lack of jobs is her primary concern.

Ginger says she has seen improvements in health services and education now that the Nisga'a are in charge of them. But she worries there won't be any money to pay for them if there aren't any jobs.

Jobs create income, and income is taxed and brings in revenues — meaning the nation wouldn't have to draw as much from the reserves of its $200 million settlement.

Still, Ginger Gosnell is positive overall about the treaty — even though she voted against it 20 years ago.

She says she didn't think people fully understood the deal they were voting on. Today, Ginger Gosnell says she sees its benefits.

"I feel like our identities and our culture are strengthened because of it," she said.

"There's a pride, there's empowerment that comes from not being part of the Indian Act and recognizing that the decisions that we make are ours."