Highway of Tears communities want fixes from B.C.

Recommendations not implemented after inquiries into missing, murdered women and girls

Sally Gibson has been waiting nearly two decades for answers about what became of her niece, a 19-year-old forestry student from a small First Nation in northern British Columbia who vanished along the Highway of Tears.

There's the official story: Lana Derrick was out with some friends and at some point ended up in a car with two unidentified men, with whom she was last seen at a gas station along Highway 16 near Terrace in the early morning of Oct. 7, 1995.

But that's just one of the many theories, rumours and guesses Gibson and her relatives have heard over the years, a painful reminder that no one — not the family, not the police — has any idea about what happened.

"We have heard so many different stories and have been told so many different things that we don't even know," said Gibson from her home in Gitanyow, the First Nations reserve where Derrick grew up.

"It isn't like Lana died and we went and buried her and the pain will go away. She totally disappeared. That's an open wound."

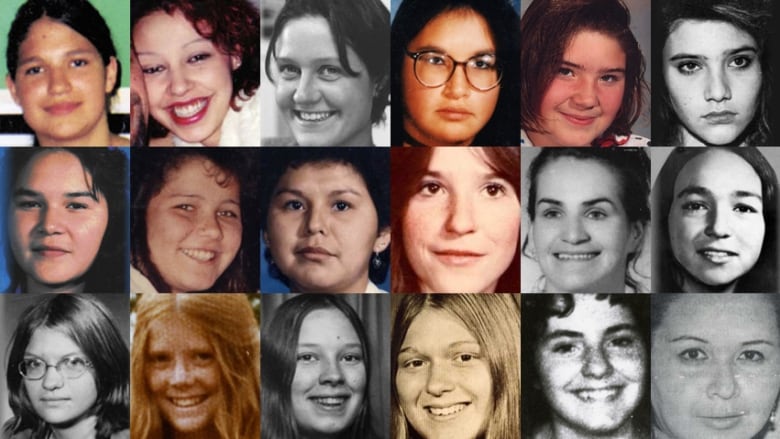

Derrick's disappearance brought her family into a community of loss and despair, joining the relatives of at least 18 women and girls who disappeared or were murdered along Highway 16 and two adjacent highways.

- TIMELINE | 18 women missing on Highway of Tears

- CBC Digital Archives | B.C.'s infamous Highway of Tears

There are the yearly walks. The memorial ceremonies. And the shared frustration that the provincial government has yet to act on dozens of recommendations to protect vulnerable women in B.C.'s north.

First Nations groups and municipal officials say the province should have acted years ago using a blueprint it already has: a 2006 report with 33 recommendations to improve transportation, discourage hitchhiking, and prevent violence against aboriginal women and girls.

- Top Mountie 'surprised' by high number of murdered, missing aboriginal women

- Visit CBC Aboriginal for more top stories

That report was endorsed by a public inquiry report released in December 2012, which called for urgent action.

The 2006 report was crafted by several First Nations groups after the Highway of Tears Symposium.

Its first recommendation was a shuttle bus network along more than 700 kilometres of Highway 16 that runs from Prince Rupert to Prince George.

Other recommendations included education for aboriginal youth, improved health and social services in remote communities, counselling and mental health teams made up of aboriginal workers, more comprehensive victims' services, and, of course, money to pay for it all.

Transit links key

Wendy Kellas, who works on the Highway of Tears issue for Carrier Sekani Family Services, wants provincial funding to examine whether any of the recommendations need to be updated. For example, the report called for more phone booths along the highway, while the focus now would be on mobile phone coverage, she said.

Still, she said most of the 2006 recommendations remain relevant, including the need for better services not only for aboriginal women, but also for the families of the murdered and missing.

And the proposed shuttle service is needed as much as ever, she said. For First Nations women who can't afford their own vehicle, there are still few options if they need to travel for groceries, appointments or to visit family.

"I believe it is still necessary," said Kellas.

"It would have to be a system, very co-ordinated to make sure people in the more rural communities are able to get into the urban centres for the basic necessities of life."

The 2006 symposium was revived by a public inquiry that examined both the Robert Pickton serial killer case and the broader issue of murdered and missing women.

Commissioner Wally Oppal called for immediate action to improve transportation along the Highway of Tears and said the government should implement the 2006 recommendations.

But there has been little effort to hold consultations, and internal government briefing notes revealed work on the file was stalled for much of the past year. The province said it had to put its work on hold when families of women in the Pickton case launched lawsuits last year.

Justice Minister Suzanne Anton and Transportation Minister Todd Stone have declined repeated requests for interviews.

Transportation in the north is worse than I've ever seen it.- Smithers Mayor Taylor Bachrach

Anton insists the highway is safe, pointing transportation options including a health shuttle for medical patients and Greyhound bus service, which was dramatically cut last year.

Taylor Bachrach, the mayor of Smithers, said Anton appears to be suggesting nothing more needs to be done.

"Some of her comments seem to be trying to justify the status quo or suggest the status quo is adequate," said Bachrach.

"Transportation in the north is worse than I've ever seen it."

Nevertheless, Bachrach said he's hopeful the province will actually start its long-delayed Highway of Tears consultations soon.

Transportation Ministry staff planned to attend a meeting with the Omineca Beetle Action Coalition, of which Bachrach is a member, last Friday, and Bachrach said he expected more such meetings to follow.

"I am keen to give the government the benefit of the doubt. If they're willing to work on this, I think communities are, too."

Highway of Tears victims

The following is a list of the 18 women and girls whose deaths and disappearances are part of the RCMP's investigation of the Highway of Tears in British Columbia. The women were either found or last seen near Highway 16 or near Highways 97 and 5:

- Aielah Saric Auger, 14, of Prince George was last seen by her family on Feb. 2, 2006. Her body was found eight days later in a ditch along Highway 16, east of Prince George.

- Tamara Chipman, 22, of Prince Rupert was last seen on Sept. 21, 2006, hitchhiking along Highway 16 near Prince Rupert.

- Nicole Hoar, 25, was from Alberta and was working in the Prince George area as a tree planter. She was last seen hitchhiking to Smithers on Highway 16 on June 21, 2002.

- Lana Derrick, 19, was last seen in October 1995 at a gas station near Terrace. She was a student at Northwest Community College in Terrace.

- Alishia Germaine, 15, of Prince George was found murdered on Dec. 9, 1994.

- Roxanne Thiara, 15, of Quesnel was found dead in August 1994 just off Highway 16 near Burns Lake.

- Ramona Wilson, 16, of Smithers was last seen alive in June 1994 when she was believed be hitchhiking. Her body was found 10 months later.

- Delphine Nikal, 16, of Smithers was last seen in June 1990, when she was hitchhiking from Smithers to her home in Telkwa.

- Alberta Williams, 24, disappeared in August 1989 and her body was found several weeks later near Prince Rupert.

- Shelley-Anne Bascu of Hinton, Alta., was last seen in 1983.

- Maureen Mosie of Kamloops was found dead in May 1981.

- Monica Jack, 12, is the youngest victim. She disappeared in May 1978 while riding her bike near Merritt. Her remains were found in 1996.

- Monica Ignas, 15, was last seen alive in December 1974 and her remains were found five months later.

- Colleen MacMillen, 16 was last seen alive in August 1974, when she left her family home in Lac La Hache, B.C., with a plan to hitchhike to visit a friend. Her remains were found the following month. In September 2012, the RCMP announced DNA evidence led them to believe Bobby Jack Fowler, who died in an Oregon jail in 2006, killed MacMillen.

- Pamela Darlington, 19, of Kamloops was found murdered in a park November of 1973. The RCMP say they suspect Bobby Jack Fowler was responsible for Darlington's disappearance, but they don't have conclusive proof.

- Gale Weys of Clearwater was last seen hitchhiking in October 1973 and her remains were found in April of the following year. The RCMP say Bobby Jack Fowler is also suspected in her death.

- Micheline Pare of Hudson Hope was found dead in 1970.

- Gloria Moody of Williams Lake area was found dead in October 1969.

Sources: The Canadian Press, Highway of Tears Symposium