Want to do something to help the environment? Start by protecting land, charities say

Loss of greenspace to forestry, agriculture and development is a significant driver of climate change

Our planet is changing. So is our journalism. This story is part of a CBC News initiative entitled "Our Changing Planet" to show and explain the effects of climate change. Keep up with the latest news on our Climate and Environment page.

Not everyone is rich enough to see part of the planet they want to protect, and just decide to buy it.

But Dax Dasilva is. The B.C.-raised, Montreal-based tech entrepreneur recently donated $14.5 million to the B.C. Parks Foundation. That cash, the largest private donation in the foundation's history, will ensure two ecologically sensitive parcels of land will never be developed.

"In order to fight climate change, in order to protect species and ecosystems, we need to have more investment," said the multimillionaire, who recently stepped down as CEO of Lightspeed to spend more time with his environmental charity, Age of Union.

"There is this doom and gloom narrative around the environment, and I think we have to turn that around to a narrative of hope, especially with everything we have to accomplish."

The donation will help protect the French Creek Estuary, a migrating ground for thousands of eagles on eastern Vancouver Island near Qualicum Beach, and the Upper Pitt River watershed, northeast of Vancouver, which is home to salmon spawning grounds, a herd of elk and grizzly bears. Together, the donation will protect more than 300 hectares.

Rich people buying up land to conserve it is an old practice, including the oil-rich Rockefeller family's major contributions to the U.S. National Park system.

But as the climate crisis intensifies, and people's desire to do something in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges grows, the idea of buying land to protect it is a tangible way for people to take action, according to Andrew Day, the president of the B.C. Parks Foundation.

"The more you destroy land, the worse the climate effects are," he said.

Growing interest in protecting land

While we often talk about greenhouse gas emissions from activities like driving or eating meat, the loss of carbon-absorbing green spaces is also a major contributor to climate change, according to the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

It's not just the super-wealthy trying to make a difference by protecting them.

The French Creek Estuary purchase shows how a combination of big and small donations can together protect sensitive ecosystems.

For example, the land owners donated more than half the land's value, a gift of more than $3.2 million. Dasilva's donation covered $1 million and the District of Nanaimo put in $400,000. The other $500,000 came from a crowdfunding campaign, where concerned citizens could offer up any sum of money.

"Dax is really shoulder-to-shoulder with tens of thousands of people who are supporting us in these land purchases," said Day. "It certainly inspires other people."

In 2021, environmental charities accounted for 5.1 per cent of online charitable donations, according to the group CanadaHelps.org. That's far less than donations to health, social services, and religious charities.

However, selling or donating land to a conservation organization is also something that is on the rise, according to Carey Hamel, the director of the Nature Conservancy of Canada's Manitoba Region.

"It's more people calling us and wanting to leave a legacy, fully understanding the importance of their land and the role it can play in a healthy planet," he said.

Land values play a role

Hamel explains that as land values have risen, people have been pleasantly surprised to find out how much their land is worth.

Rather than maximize profit by selling to a developer, some owners choose to sell part of the land to an organization such as the Nature Conservancy, and donate the rest to the same organization. That way they get three benefits: the profit from the portion sold, the tax benefit from the portion donated, and the knowledge it will remain protected.

"The donors that come to us, they know these places are special," Hamel said.

That was the case with Thor Vikström, who recently donated Île Ronde, a 2.8-hectare island nestled between Montreal and Laval, to the Nature Conservancy of Canada.

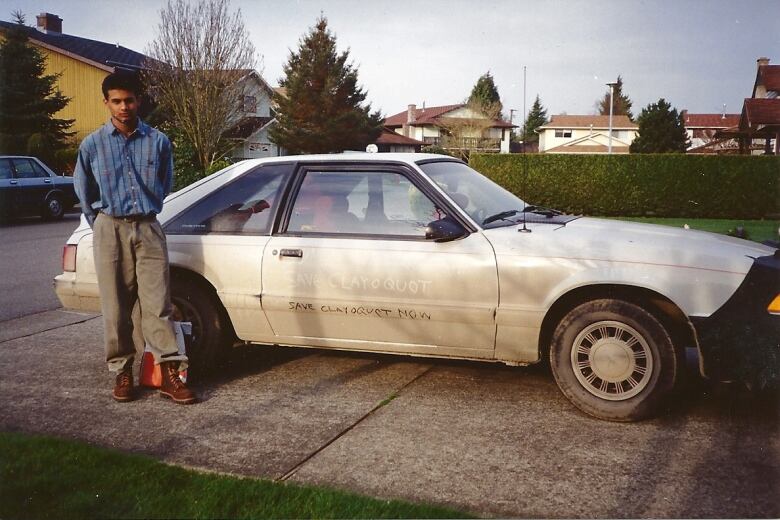

There's a personal connection behind Dasilva's donation, too. His environmental-activist roots go back to when he was a teenager, joining the protests against old growth logging at Clayoquot Sound. So choosing to protect land in B.C. made sense.

"It was B.C. that made me fall in love with our natural world." said Da Silva.

Traditional land use continues

Dasilva's donation was met at first with some skepticism from members of the Katzie First Nation, whose traditional territory includes the Pitt River watershed.

"Initially, there was concern," said elected band councillor Rick Bailey, explaining he and other members of the First Nation were worried that the B.C. Parks Foundation would try to stop them from hunting elk and other traditional uses of the land.

The First Nation has been working for decades to protect it. At one point a developer wanted to mine it for gravel, at another there were plans for a resort. Once Bailey learned traditional practices could continue and the land would be protected, he was grateful.

The B.C. Parks Federation said it is working on a memorandum of understanding with the Katzie First Nation about stewardship and use of the lands.

"We will continue to use the land and resources as we always have," Bailey said.

And if it takes wealthy donors to protect land and keep it that way, so be it, he added.

"There's more and more of it happening, and I'm happy to see it," Bailey said. "We didn't have the money."