Canadian study raises new questions about why southern resident killer whales are in decline

UBC research challenges assumption that endangered orcas don't have enough to eat in summer

A team from the University of British Columbia says the assumption that southern resident killer whales are in decline due to lack of chinook salmon in Canadian waters does not hold up under scrutiny.

Instead, their new study suggests declining chinook stocks are only part of the problem facing the critically endangered orcas, and that researchers need to look beyond the Salish Sea for answers.

Andrew Trites, the study's co-author and director of UBC's Marine Mammal Research Unit, called the findings published earlier this month in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences unexpected.

"It doesn't fit with what anybody believed was going on," he said.

In the last decade, the number of southern resident killer whales in the world has dwindled to just over 70. Observers believe many in the group are increasingly malnourished and skinny.

Over the past five years, the population has been returning to the summer feeding ground in the Salish Sea later every year.

These factors, combined with declining chinook stocks, have led to the assumption that the orcas were staying away from the Salish Sea because they just weren't finding enough to eat.

Comparing whale populations

Wanting to test that conclusion, the UBC team set out to compare the southern residents to their thriving northern resident killer whale relatives, who also feed primarily on chinook salmon, and whose numbers have grown to over 300.

According to Trites, the northern resident killer whales "are fatter on average and the population is increasing."

"And so the presumption has been even though they too are feeding on the declining population of chinook, they've got more fish available to them and that's why they're doing better."

By using ship-based multifrequency echosounders — what Trites calls the world's most expensive fish finder — the researchers evaluated the size and availability of chinook to each killer whale population in 2018 and again in 2019.

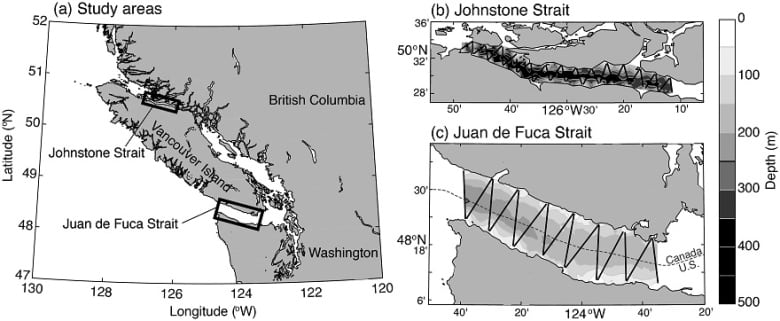

They focused on two geographical pinch points where chinook pass through as they migrate in from the ocean. For southern residents they looked at Juan de Fuca Strait between the southern tip of Vancouver Island and Washington state in the U.S.; for northern residents they studied Johnstone Strait between the northeastern edge of Vancouver Island and mainland B.C.

Salmon surprise

Contrary to expectations, both habitats showed similar distributions of schools of chinook.

Even more surprising was the discovery that the schools in the southern habitat contained four to six times the number of fish as the northern habitat.

"It's a really important finding because we're the first team of researchers to go out to test the belief that there, in fact, is a shortage of chinook. And we didn't find it," said Trites.

"So it tells us then the reason why [the southern resident killer whales] are not coming back in is not because there's an absence of salmon. It's something else going on."

Southern resident killer whales are officially listed as a species at risk by the Canadian government.

Chinook stocks still not healthy

Concern over their survival has prompted action on many fronts, including changes to marine traffic and numerous chinook salmon conservation and restoration efforts.

One of the more interesting campaigns saw U.S. biologists and a First Nation attempt to feed an ailing southern resident known as J-50 live chinook salmon off a boat.

Trites pointed out that the study does not indicate that chinook stocks are healthy.

"It doesn't mean that salmon are in great condition because they're not," he said.

"But the fact is that there are more fish available to [southern residents] here than to the growing northern resident killer whale population. So that should get people to open their eyes and now ask questions."

Trites believes more study beyond the conditions in the Salish Sea are needed to understand what is happening to southern residents.