B.C.'s chief coroner looks at new approach to tackling the overdose crisis

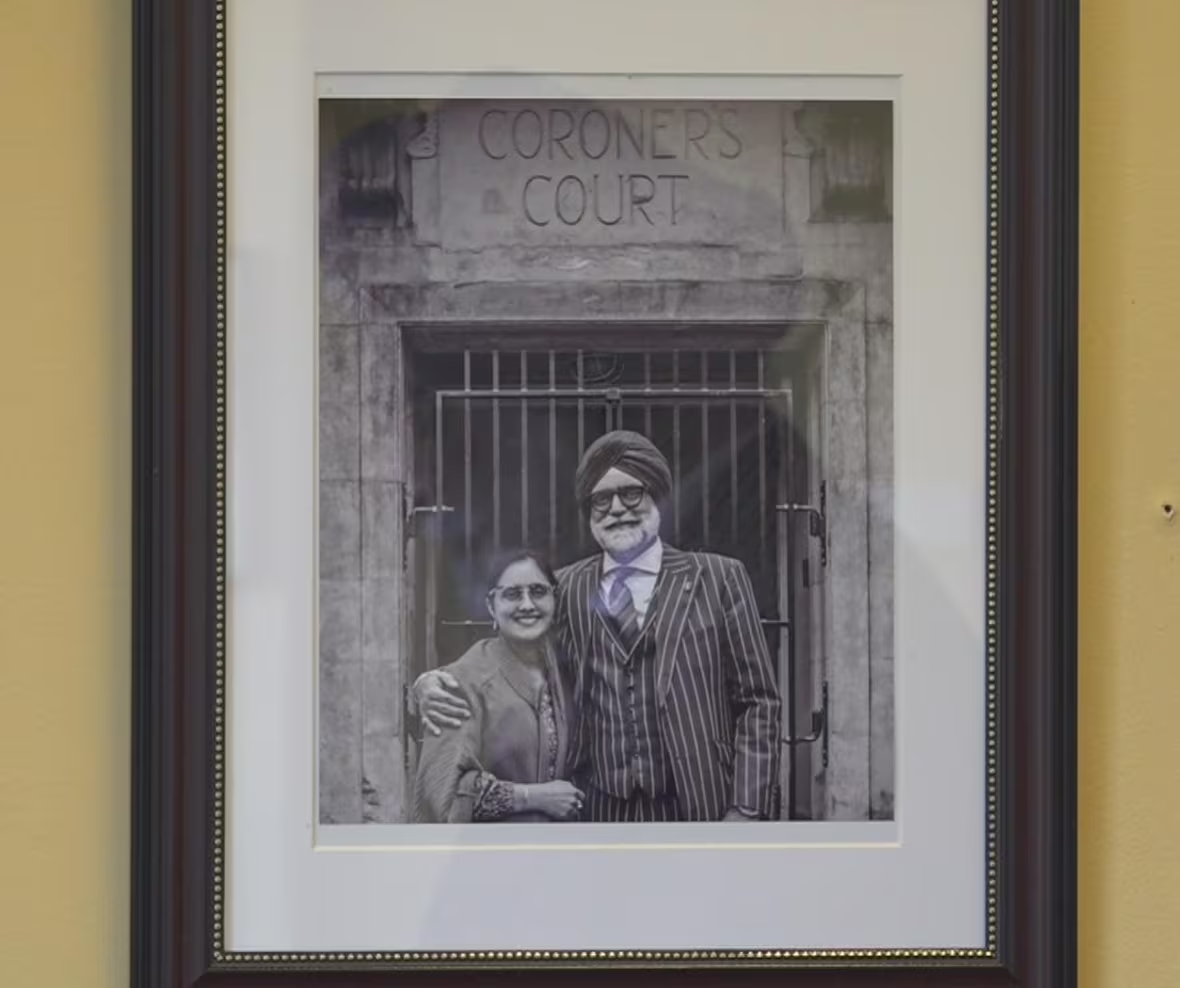

Dr. Jatinder Baidwan takes the reins of the B.C. Coroners Service as drug deaths continue unabated

Nine years after the start of a public health emergency that has killed more than 16,000 people, B.C.'s new chief coroner is taking on the crisis in a new way — an approach he says is, perhaps, a little less political than his predecessor.

"As the chief coroner, it's my responsibility not to advocate for any particular group out there. But to advocate for all British Columbians … for those who have died," said Baidwain, who started his five-year term in August.

Baidwan doesn't profess to have all the answers on how to stop overdose deaths and the cycle of addiction.

But he is concerned that harm reduction advocates and those who advocate for abstinence-based treatment and recovery are so ensconced in their stance that they won't talk to one another.

"How do we, as the coroners service, get people with all ideas on how to fix this issue around a table and get them to talk to one another?"

Baidwan joined the B.C. Coroners Service in 2016 as a chief medical officer.

His 20 years working as a medical officer in the British Army has taken him all over the world— Iraq, Bosnia and parts of Africa. Baidwan also worked in the Household Cavalry, guarding the Queen.

Baidwan says he wants to be more strategic in the way his agency puts out information on toxic drug deaths and also highlight other preventable deaths like those of unhoused people and deaths from intimate partner violence.

Speaking from his office in Victoria overlooking the Inner Harbour, Baidwan says he and his team are moving to deeper analysis of trends in overdose deaths, instead of fixating on monthly overdose numbers to tell the story. He's concerned the public becomes desensitized to the deaths and begins to tune them out.

"I do worry that flooding the media with information sometimes isn't the best way of doing it," he said. "Any death, one death from this scourge is one death too many."

Some harm reduction advocates initially feared this meant Baidwan was moving his focus away from opioid deaths.

Leslie McBain, who has pushed for a safer supply of regulated opioids ever since her son, Jordan, died of an overdose in 2014, says after a meeting with Baidwan this month, she's convinced that's not the case.

"I'm very impressed by this man, he's a straight shooter," said McBain, of Moms Stop the Harm. "He absolutely knows on a deep level about the opioid crisis. He may not give his deep opinions but, as all coroners do, he will give recommendations on ameliorating the situation."

"We are not stopping the attention we've given in the past," Baidwan said. "In fact, we're increasing the amount of time we're thinking about drug deaths."

For example, Baidwan says he's trying to enhance partnerships with the B.C. Centre for Disease Control so some of their data analysts and public health researchers can improve the analysis done on overdose deaths.

Different approach from his predecessor

It's a different approach compared to Lapointe, who led the coroner service for 13 years.

But the public — and eventually the NDP government — were not always on side with her recommendations, particularly as open drug use in playgrounds, parks and city sidewalks led to calls to walk back the decriminalization experiment.

Lapointe had also called for safer supply drugs to be provided without a prescription, a recommendation swiftly rejected by the government. Health Minister Josie Osborne announced last month a stricter approach, requiring people who use prescription opioids to take them under the supervision of a pharmacist.

Lapointe retired in February, vocal about her frustration at how polarized and political the debate over drug policy had become. She told CBC's The Current she left the job angry at the "lackadaisical" response to the toxic drugs crisis.

Baidwain says he will let the data around overdose deaths speak for itself.

B.C.'s low autopsy rates

For example, Greg Sword pressed for an autopsy to give him more answers about the death of his 14-year-old daughter Kamilah.

She died in her bedroom in Port Coquitlam in the summer of 2022 from an overdose. The coroner's report concluded the teen's death was caused by cocaine and MDMA use, although there were other drugs in her system, including hydromorphone — a medication prescribed under B.C.'s safer supply program.

Sword was convinced the hydromorphone in her system was downplayed as a cause of death.

While Baidwan couldn't speak specifically to Kamilah's case, he said an autopsy would not have made a difference in understanding the cause of death.

"In the world of CSI, we think an autopsy will give us all the answers. Sadly, it doesn't."

B.C. has one of the lowest autopsy rates in the country. A rate that has declined steadily from 22 per cent in 1991 to 3.2 per cent in 2022, according to Statistics Canada.

However, Baidwan says those figures are misleading because they do not include autopsies performed in the health system — when someone dies in hospital, for example — which makes up about 10 per cent of deaths.

Baidwan is advocating for more coroners to be hired, as the number of deaths each year in B.C. grows due to the aging and growing population.

"We've continually hired more coroners over the last few years. And the government has been supportive in allowing us to hire the right number of people."

That, Baidwan said, will allow the B.C. Coroners Service to complete its investigations faster, giving families the answers they're looking for.