How U.S. sanctions on Venezuela have left a dozen oil tankers idling with no place to go

Estimates suggest there's up to 7 million barrels of Venezuelan crude floating in tankers with no destination

The sanctions the U.S. slapped on Venezuelan oil last week are playing havoc with the tankers that ship crude around the world, and throwing energy prices off-kilter in the process.

Last Monday, the U.S. imposed sanctions on Venezuela's state-owned oil company Petroleos De Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA for short) in an attempt to starve the regime of Nicolas Maduro of the money he needs to cling to power.

The sanctions effectively froze all of PDVSA's assets in the U.S. and require that any money made in deals between the company and U.S. firms be held in escrow accounts that will be inaccessible as long as Maduro remains in power.

In addition to making it harder for Venezuela to export oil, the sanctions also make it harder and more expensive for U.S. companies to send fuel products known as diluents in the other direction.

The goal was to strangle Maduro's golden goose, but an unintended consequence of that plan has left oil tankers floating around the Caribbean, unsure of where they should go to try to unload their cargo.

Killing time in the Caribbean

Ship-monitoring website TankerTrackers.com estimates there are about a dozen oil tankers idling either off the Venezuelan coast or elsewhere in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, about half of which are loaded up with Venezuelan crude that suddenly has no place to go.

Under normal circumstances, the vast majority of Venezuelan crude is destined for refineries on the U.S. Gulf Coast. With those customers effectively blocked off, that oil is having a tough time finding alternative customers.

Oil blends vary wildly in chemical composition, and there aren't many refineries anywhere near Venezuela that can process the heavy blend the country produces. Most are found in the U.S., which is bound by the sanctions. Many Chinese and Indian refineries are calibrated to process this crude and would likely happily buy it, but the economics of hauling anchor across the Pacific on a whim make that an unappealing prospect.

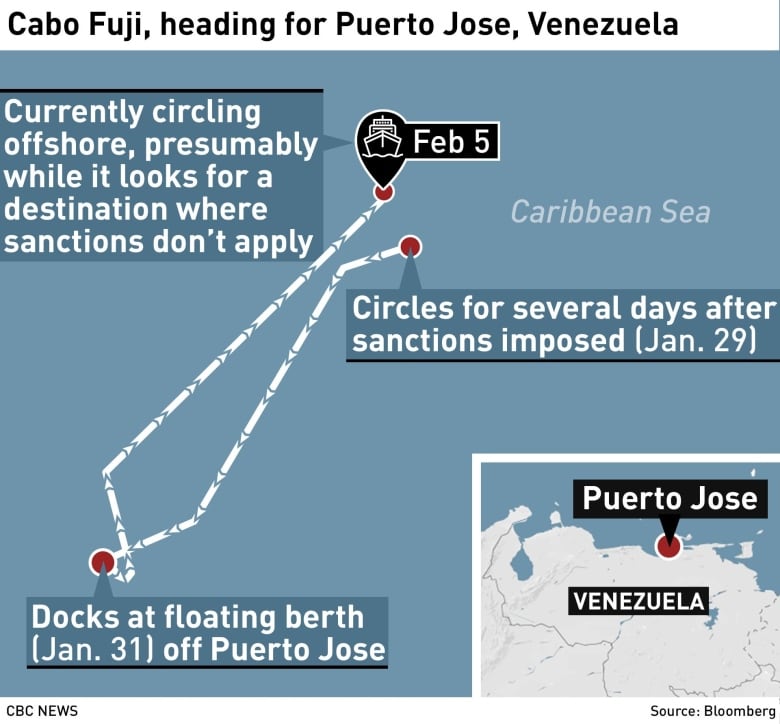

One ship in particular, the Cabo Fuji, seems to be having a hard time making up its mind about where it should go next. According to ship-tracking data compiled by Bloomberg, the Cabo Fuji entered Venezuelan waters on Jan. 28, the day the sanctions hit. The ship went around in circles for three days before moving up to an offshore loading berth at the Puerto Jose terminal to fill itself with Mayan crude on the 31st. It then went back to right about where it was before, and has been lumbering around there ever since.

TankerTrackers says it is not uncommon for large tankers to spend a few days at bay when loading and unloading in Venezuela — or indeed anywhere else in the world. But the sheer number of ships seemingly waiting out the dispute is above and beyond what many industry watchers consider normal.

Reuters News Agency calculated on Monday that roughly seven million barrels of oil is currently floating in tankers in the Gulf of Mexico, while ships decide where they will go with their cargo and who will pay for it.

The sanctions are wreaking havoc on the import side, too. Venezuela's thick and heavy oil needs to be mixed with diluents in order to be transported, and the country imports almost all of those diluents from overseas. Diluent shipments are covered by the sanctions.

According to Bloomberg data, the Aphrodite Horizon left the U.S. port of Lake Charles, La., on Jan. 26 carrying a diluent called naphtha bound for Puerto Jose.

By the time news of the sanctions came down, it was well on its way through the Gulf of Mexico and about to veer sharply south toward Venezuela when the ship decided to do a U-turn and head back toward the U.S. It has spent the week since basically floating around the Gulf, seemingly headed for nowhere in particular.

There's a steep price to pay if the ship delivers its cargo to its original destination, so the ship's owners are likely trying to find an alternative market for the thousands of tonnes of naphtha they're carrying — which is easier said than done on the fly.

Economist Rory Johnston of Scotiabank says the strange shipping activity shows the sanctions seem to have caught everyone by surprise. "Theoretically, we should see those barrels being rerouted, but these things aren't really heading anywhere," he said in an interview.

Under normal circumstances, the global oil market has more than enough buyers and sellers to find a new balance any time there's disruption on the scale of the roughly 500,000 barrels of oil that Venezuela normally ships to the U.S. every day.

But the current situation is anything but normal. "Those tankers aren't moving anywhere [and] everything's grinding to a halt," Johnston said, "which means the impact on the oil market is going to be bigger than we thought."

More appetite for Canadian crude

That's especially true for Canada. Venezuela's heavy oil blend is very similar to the type that comes out of Canada's oilsands, which is known as Western Canada Select. So, in theory, all those U.S. refineries tailor-made for heavy Venezuelan crude should have more of an appetite for Canadian WCS.

Mandatory production caps announced by the Alberta government late last year were already causing the price of WCS to surge even before the sanctions against Venezuela, and the price gaps between light and heavy crude blends in the Gulf are getting even thinner.

"Theoretically, you're going to pull more and more of that flexible Canadian oil by rail capacity down to the Gulf," Johnston said, "but it's not like we're going to fill in for the entire half million barrels per day."

While there's probably some benefits to be had for Canadian producers from the unrest, a flotilla of idling oil tankers is going to have all sorts of unintended consequences on the market.

"Things are happening so quickly that everyone's more or less just kind of paralyzed .. as to ... where to go next," Johnston said.

"Based on how things are jammed up, it doesn't seem like anybody had a contingency plan."

With files from Reuters