Panama Papers taunt the masses with more proof that game is rigged

Massive data leak is only the latest of many signs that the ultra-rich are playing by different rules

The shills for the people who really run the world have been pulling all-nighters, crafting avowals in the casually arrogant language of the ultra-entitled.

Statements are coming from different countries in different tongues, but the message is similar: Come on, folks, move along, back to work, let's go, show's over.

Dmitry Peskov, a mouthpiece for Russian President Vladimir Putin, contemptuously dismissed stories about Sunday's titanic data leak from a secretive Panamanian law firm that specializes in creating hiding places for extreme wealth.

"Nothing much new here," sneered Peskov (in a sense, at least, stating the obvious).

Other national leaders and politicians — from Rio to Reykjavik, from London to Kyiv, from Islamabad to the Beijing politburo — are equally annoyed.

That they and their relatives might park enormous sums of money offshore is a reality not meant for popular consumption.

- Panama Papers: Document leak exposes global corruption, secrets of the rich

- RBC denies wrongdoing after being named in Panama Papers

- Big names implicated in Panama Papers offshore banking leak

- Panama Papers: Quebec lawyer based in Dubai linked to Mossack Fonseca

In Putin's case, the data leak shows that about $2 billion US in hidden money leads back to him, one way or the other.

It turns out Sergei Roldugin, a concert cellist, lifelong friend of the president and godfather to one of his children, owns companies that have made hundreds of millions of dollars. Playing the cello in Russia is, apparently, a pretty good gig.

Discretion will cost you

Mossack Fonseca, the law firm in Panama whose principals must be pretty nervous right now — the Russian elite don't play games with people who threaten their wealth — protested that allegations it hides income for the rich "are completely unsupported and false."

To be clear: this is the same company that offered an American millionaire fake ownership records so she could withdraw money from her offshore company without revealing she owned it, the better to hide her millions from the IRS.

"We may use a natural person who will act as the beneficial owner," Mossack Fonseca advised Marianna Olszewski when proposing that a 90-year-old British man act as the dummy owner in her place.

"Since this is a very sensitive matter, fees are quite high."

Because, you know, discretion costs money.

According to a leaked memo from one of Mossack Fonseca's executives, "95 per cent of our work coincidentally consists in selling vehicles to avoid taxes."

In Western countries (one suspects that any official inquiry in Russia, as an example, is already wrapped up), one tax authority after another is up on its hind legs, promising intense investigations.

And, of course, Mossack Fonseca, along with various people on its client list, is promising full co-operation. Through the very best lawyers, of course. Let's not forget who these people are.

They, along with thousands of other less-prominent names exposed in the data dump, belong to a private club that's just really a great place to be a member.

Once you're in, investigators become more sympathetic, regulators become more forgiving, and taxes become much more avoidable.

Law becomes a relative concept. You actually get to make laws, or at least fund the people who do, which can amount to the same thing.

Plus, you get fabulous stock tips.

'Suspiciously persistent' profits

As The Economist, a conservative magazine not renowned for cheering on the proles, put it last week: "the game may, indeed, be rigged."

The editorial, uncharacteristically titled "The problem with profits," went on to explain. It called American corporations' record-high profits "suspiciously persistent."

A few decades ago, a very profitable company had a 50 per cent chance of maintaining that profitability after 10 years. Now, it's 80 per cent.

"A tenth of the economy is at the mercy of a handful of firms — from dog food and batteries to airlines, telecoms and credit cards. A $10 trillion wave of mergers since 2008 has raised levels of concentration further," The Economist wrote.

Big firms, it argued, ensure that small firms stay small, with help from their friends in government.

"America is meant to be a temple of free enterprise. It isn't," the magazine said.

Now, don't forget: America's economy, compared to most of the world, is a model of transparency and rule of law.

Billions and The Big Short: Art imitating life

Depressing? Don't turn to entertainment for escape.

The Big Short, which did wonderfully in theatres last year, portrayed a real-life group of savvy money men who watched their Wall Street colleagues infect the world's economy by peddling billions of dollars worth of garbage camouflaged as rock-solid securities, then made more billions betting against them.

Showtime's new drama Billions proceeds from the basic assumption that the real money is made by traders operating on inside information, at the expense of all the ordinary chumps naively betting their savings in a gamed system.

The prosecutor representing those chumps and charged with going after the traders is a flabby, unethical, obsessive man who is into S&M. As the series progresses, you find yourself rooting for his enemy, a slim, good-looking hedge fund founder described as a human nation-state, someone who doesn't have to seek out sources for insider info, because they come to him, a torrent of supplicants looking for profitable favours.

- Document leak exposes global corruption, secrets of the rich

- Iceland PM faces protests over Panama Papers

- PHOTOS | Big names implicated in data leak

- RBC denies wrongdoing after appearing in Panama Papers

After thwarting the prosecutor yet again, he walks off in one episode to the anthem Tubthumping: "I get KNOCKED DOWN! But I get up again..."

Go ahead. Watch it, then go take a look at your RRSP statement and try to remember the last time it grew by 10 or 15 per cent in a single year.

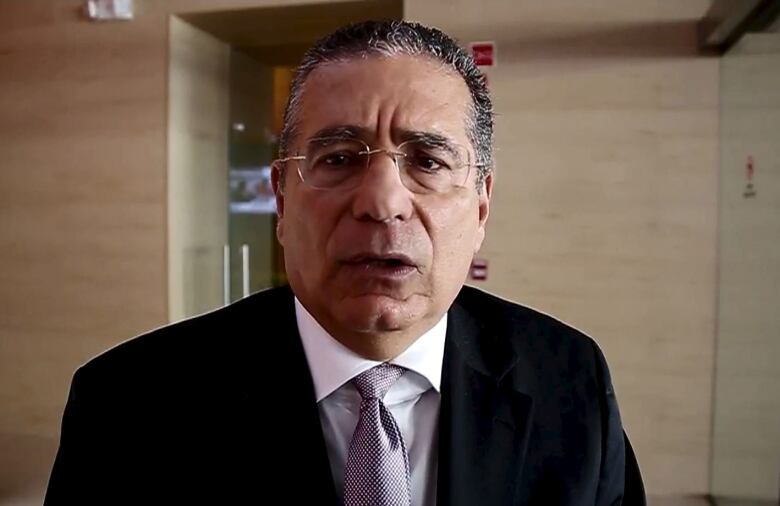

Anyway, it was Mossack Fonseca founder Ramon Fonseca who most succinctly spoke for every member of the game-rigging club Monday.

The data leak, he said, was part of "an international campaign against privacy. Privacy is a sacred human right. There are people in the world who do not understand that."

Translation: there are things the rest of us aren't supposed to see. Now, back to your illusions.