Trump's Huawei threat a risk to Canadian and global tech in 2019: Don Pittis

Huawei clash could be a trial run for U.S.-China tech conflict that would put Canada in a difficult spot

Reports that U.S. President Donald Trump is threatening to up the stakes in his battle with Chinese tech giant Huawei in 2019 seem at first glance the kind of Trumpian sniping the world has grown to expect.

But if it is true, as Reuters reported this past week, that Trump may sign an executive order prohibiting U.S. firms from buying Huawei technology, the issue goes far beyond Huawei and 5G wireless networks to one that could transform the global tech industry. And not for the better.

The reason is that Huawei — and Chinese chip maker ZTE, which the U.S. president also threatened to ban — are not unique. Instead, they are merely a couple of examples of Chinese technology that is not just catching up to the best in the world, but beginning to exceed it.

China, tech superstar

For Canadian technology businesses trying to see their way forward, facing a global tech leader that is in conflict with the U.S. is an unfamiliar experience.

Despite the Soviet Union's space race victory with its 1957 launch of Sputnik 1, humanity's first artificial satellite, the collapse of the Soviet communist empire nearly 30 years ago revealed a creaking technological relic.

Canadian technology experts say China is something entirely different and people who try to make the comparison with Eastern Europe, where the Trabant was the communist answer to the BMW, have it all wrong.

Pretty well everyone now knows that China is a developing technological competitor. But there are growing indications that, barring some political or economic cataclysm in China, or a sudden technological golden age here in North America, China is on its way to becoming not just a technological powerhouse, but the technological powerhouse. It is becoming the global tech superstar.

And at some point Canada is going to have to make some crucial decisions on how it will cope with that change. And it may find its interests do not coincide with those of the United States.

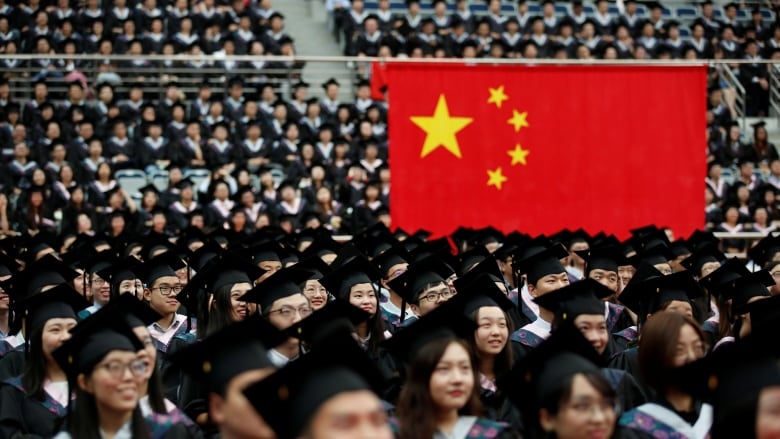

"On Chinese technological prowess, they are now graduating twice as many graduates as the United States from university, but they're graduating five times as many STEM graduates," says Gordon Houlden, director of the University of Alberta's China Institute. STEM stands for science, technology, engineering and math, the kind of graduates who make a real difference in the race for world-beating know-how.

Leapfrogging the world

In many ways, the explosive developments in Chinese science and technology have no equivalent since pre-war Germany leapfrogged the world in many areas of science and industrial production.

Over the past month, the arrest in Canada of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou, at the request of U.S. prosecutors, has helped focus attention on that company.

While the charges against Meng have nothing to do with 5G — she's accused of misleading financial institutions about her, and Huawei's, relationship with a company that did business with Iran — the case has spotlighted Huawei's state-of-the-art contributions to communications technology.

There has been much debate over whether Huawei's involvement in 5G, or even the sale of its phones in the world market, represent� a Trojan horse for the Chinese government, giving the country's security forces backdoor access to our deepest secrets.

Not just telecom

But that focus on 5G may be misleading. For one thing, 5G is not a single gizmo. It is more accurately a kind of marketing title for the fifth generation of mobile phone technology. As such, it represents a host of technological subsets, mostly software, some of which are being developed in Canada, says R&D specialist Rick Clayton, a partner with the Ottawa-based consultancy Doyletech.

Clayton says Huawei is just one company operating in an industrial cluster in the Ottawa suburb of Kanata North, where Canadian engineers, some of whom used to be at Nortel Networks before its collapse, work on new software components.

"There's a fair bit of implicit and explicit sharing between the companies," he says, which is part of what makes an industrial cluster strong.

And this by no means applies just to the smartphone sector.

One way of sharing is to license intellectual property that someone else has already invented, says Mark Henderson, former owner and editor of the specialist newsletter Research Money.

"They can get it immediately as opposed to working it out of their lab over a period of months or years," he says.

That international sharing of technology between companies saves money and speeds up progress. The financial damage of cutting off access to intellectual property invented in China, especially as its technology pulls ahead, is hard to calculate.

Chinese open source

Another common way of sharing is called open source software, something that's been around for years and famously includes the operating system Linux, where employees from many different companies work to build and improve chunks of programming components that are widely used in the systems of those and other companies.

An increasing number of those open source projects are being invented and co-ordinated by Chinese software developers, and that trend is only likely to grow as China increases its number of STEM graduates.

Another potential mistake compounded by the focus on Huawei is thinking that China's growing technological skills are isolated in just a few areas, such as telecom.

While the experts interviewed for this piece say the U.S. still has an overall technological lead in many sectors, China is not just catching up, it is pulling ahead.

China is poised to become the next space power. This is just one reason why. <a href="https://t.co/8N6FZ4iJyq">https://t.co/8N6FZ4iJyq</a>

—@techreviewAccording to the MIT Technology Review, China has become the one to beat in space technology, while its southern city of Shenzhen is racing to outdo California's Silicon Valley as "a global hub of innovation, entrepreneurship and manufacturing."

Currently, most global products include the best innovations from around the world. U.S. firms use Chinese-invented technology and vice versa.

A Huawei executive has said the company will do absolutely anything, including opening its code to detailed inspection, to prove that it is not a threat. Whether a ban is worthwhile can only be determined by the best and most independent security experts. And banning Huawei to eliminate a purported backdoor does not guarantee U.S. systems will be secure from international hackers who have used other methods of entry.

If instead the security concerns are actually part of a political attempt by Trump to weaken China's technological advantages, the world may be on the verge of a watershed that could hurt everyone. The risk is there could be a new technological cold war that divides the world, forcing countries to choose between two increasingly incompatible technical — and political — systems.

As Gordon Houlden of the China Institute says, besides the business cost and difficulty of untangling two sets of competing technology, economic interdependence helps prevent wars. He says as an outward-looking trading nation, Canada should do everything it can to try to prevent such a technological fissure and the resulting political divide that will inevitably hurt both the U.S. and China.

Ultimately, says Houlden, if push comes to shove, Canada must stand shoulder to shoulder with the U.S., its longtime ally and security guarantor.

But avoiding a technological split into "we" and "they" is not just in the interests of Canada, but those of the global technology industry both inside and outside the American sphere.

And if that doesn't matter to you, consider this. If we gang up with the U.S. against China's increasingly sophisticated knowledge industry, maybe sometime soon we will no longer be able to get our hands on the coolest tech.

Follow Don on Twitter @don_pittis