Bill Morneau's budget challenge: Deficits and the difficulty of planning for a long future

Disappearing baby boomers and the chance of a real economic crisis make deficits riskier than in the past

As I reassured a millennial colleague the other day, in 40 years most of the boomers will be dead.

It may seem like a long time to wait for that demographic bulge to relinquish their homes or jobs, but now that the oldest boomers have reached the age of 71, the workplace changing-of-the-guard is already well underway.

- Deficit has soared ahead of March 22 budget, Bill Morneau says

- Bill Morneau tries to reassure Canadians economic growth is worth a deficit

A speedily aging and shrinking workforce is one of the more certain new variables that Canada's finance minister, Bill Morneau, must toss into the mix as he imagines the future impact of the deficit he plans to run up in next month's budget. Other variables are not so clear.

It may be no more than a persistent illusion, but it feels as if this time the global economy in general — and Canada's in particular — really are on the precipice of greater-than-usual uncertainty.

Unexpected eventualities

While there are many changes a wise government can make to adjust for unexpected eventualities, deficits represent an enduring shackle to an unknown future. There are good reasons why this matters.

Most economists agree there is nothing wrong with carrying a federal debt of between 25 and 35 per cent of GDP, especially while interest rates are so low. But running repeated deficits larger than the growth rate of the economy, popular as it may be while governments are doing it, can quickly accumulate into something far less manageable.

Angry voters

According to conventional economics, governments have two options to get rid of debt. Both require a cutback in spending. One is to freeze spending while waiting for the economy to outgrow the debt. Unfortunately a freeze feels like a cut, since spending must be reduced by the amount of the previous year's deficit.

The more urgent way to reduce debt is to take an axe to spending — as we saw after the federal debt peaked in 1997 at about 65 per cent of GDP — or raise taxes. As politicians have learned time and again, there is never a good time to slash spending or raise taxes. It makes voters mad.

Besides the great difficulty of unwinding a deficit once it exists, there are other reasons Morneau must be wary of how much he is willing to borrow.

One is the whole concept of a return to normal growth.

As we have seen in countries like Japan that have led the way on an aging workforce, normal growth rates are much lower than they were when large numbers of young families were nesting and buying things for the kids. It may be that growth rates averaging between the one and two per cent that we are currently experiencing are not so bad.

Morneau tells us that without deficit spending, Canada may head into recession. Of course that begs another question: What will the government do if a much more serious crisis arises? There are plenty of possible choices on the horizon.

Crisis ahead?

There are new worries about the stability of global banks as they set aside more money to cover expected bad loans. So far this week, Canadian bank results have not been up to their previous stunning standards.

- National Bank profits down 37% as lender writes off $145M Maple Bank stake

- Saudi oil minister's message for high-cost crude producers: 'get out' of market

Even if oil prices bounce back eventually, it won't do the federal books as much good if Canada's industry has been decimated.

Oh yes, there is still the danger of an impending housing crisis, another fall in the loonie and the ever-present danger of a U.S. recession relapse. Over a long future, interest rates, now low, cannot be predicted.

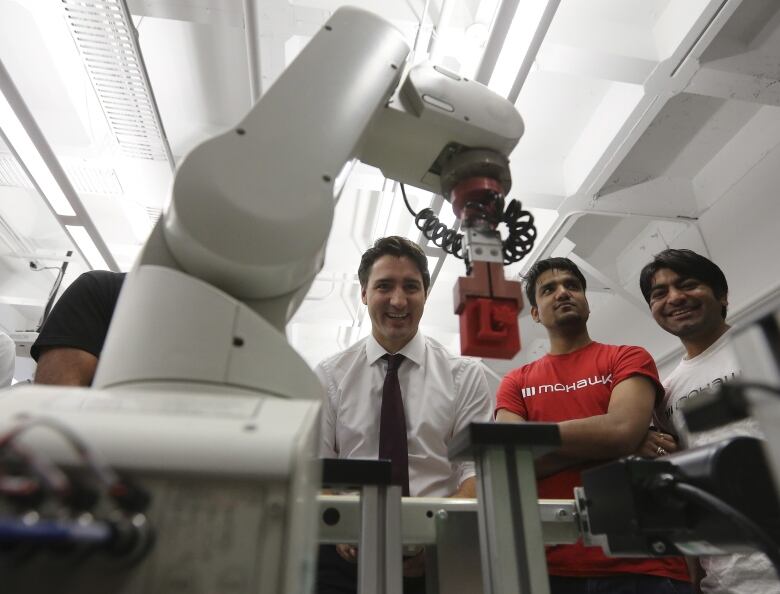

It may be that we can replace the productivity of a shrinking workforce with automation and robotics, allowing a return to four per cent growth. But unless something changes in Canada's current demographic trends, loans taken out by the government now will have to be repaid by a smaller working population.

Millennials may look forward to getting all those great boomer homes and well-paying jobs. But unless our finance minister is prudent in his budget deficit spending, those millennials may also have the doubtful pleasure of inheriting the boomers' burdensome national debt.

Follow Don on Twitter @don_pittis

More analysis by Don Pittis