How an 80-year-old manuscript renewed Black writer Richard Wright's legacy

Richard Wright went from a big name in Black American literature to being pushed to the margins until now

*This episode originally aired on May 19, 2022.

Richard Wright was the most prominent Black American writer of the 1940s. His novel Native Son about the corrosive effects of racism made him a literary star and a rarity for the time — a Black bestselling novelist.

But his tenure as an influential Black American writer only lasted about a decade. He'd fallen out of favour with readers, scholars and cultural critics alike. His writing was thought to be too preoccupied with the ways Black people were victimized and dehumanized by racism, neglecting to show the beauty and humanity of Black American life.

"Native Son was a bestseller among white readers and Wright saw it as a way for white America to wake up to what it was that they were doing to Black minds and Black souls," said Ralph Eubanks, a writer whose work focuses on race, identity and the American South.

"Yet over time, a lot of people have come to see Native Son as a book that only codifies racial stereotypes about the whole myth of the Black beast rapist."

Wright's Native Son is an unsettling, controversial and divisive book in Black American literature.

The story focuses on the protagonist, Bigger Thomas, a 20-year-old living in extreme poverty in Chicago's South Side in the 1930s. He is employed as a chauffeur by a wealthy white liberal family. One evening Mary — one of his employers — was extremely drunk, so Thomas helped her get to her bedroom. Mary's blind mother comes into the bedroom, and Thomas accidentally suffocates Mary. He is put on trial for rape and murder.

"Bigger Thomas becomes who he is … as a result of the visible and structural constraints of the way race was lived in Chicago in the 1930s and 40s," Eubanks said.

Now almost 80 years after Native Son, a rejected manuscript of Wright's novel, The Man Who Lived Underground has been published — prompting a renewed relevance of his work at a time when racist violence and police killings of Black Americans are top of mind.

'Black rage on the page'

In 1940, Jim Crow was still the law of the American South, it was the middle of the Great Migration of millions of Black Americans from the South to northern cities like Chicago. The Civil Rights movement was still 15 years away.

Wright's Native Son became a blockbuster hit, selling a quarter-million copies in three weeks. He considered this novel to be a work of protest, exploring racism, oppression and violence against Black Americans.

As a young man, Eddie Glaude didn't find Native Son to be liberating. Quite the contrary. The Princeton professor and author said he was terrified "to see that kind of Black rage on the page."

"To have it come alive was in some ways an externalization of something that I felt in me... the sense of being pent in and pent up, of the society pressing in on one's shoulders, and knowing why and being able to name it, and sitting in that rage, and spying the violence that could follow from, it was really extraordinary for me."

More harm than good

Wright was eventually pushed to the sidelines when criticism of Native Son became more prevalent. His brand of protest literature was seen as crude and doing more harm than good to the cause of Black uplift and equality.

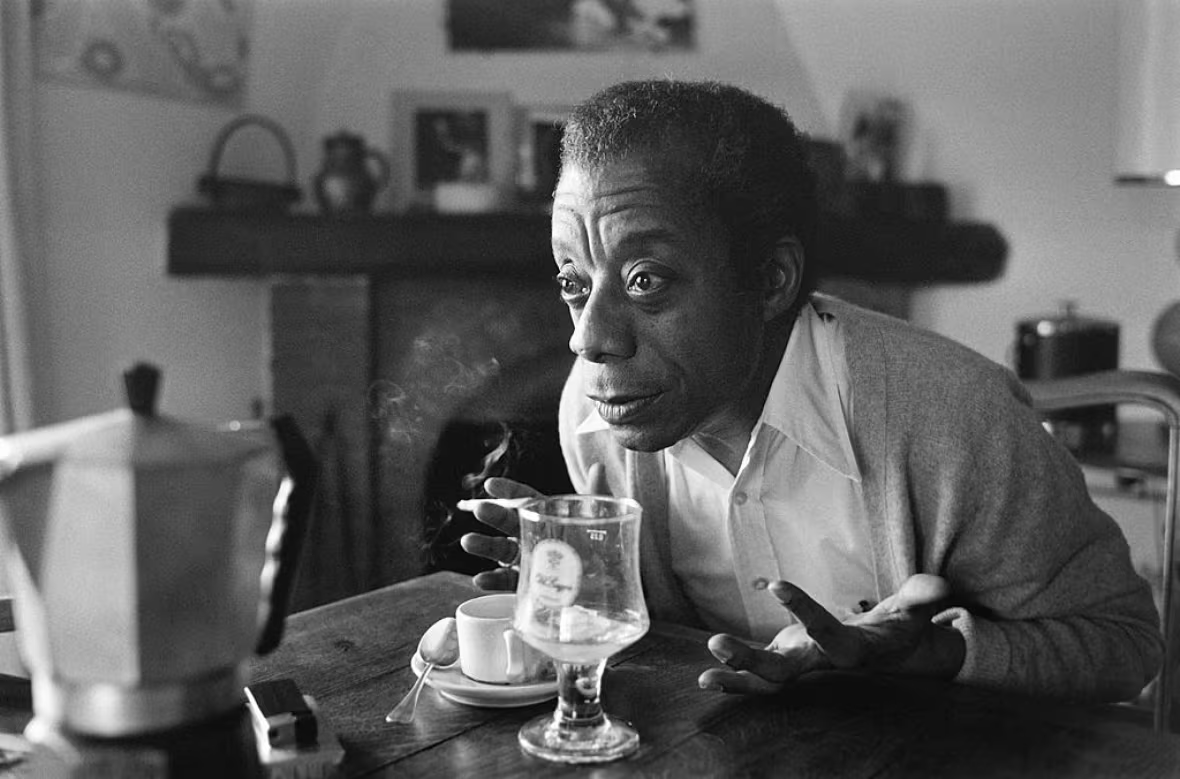

Eventually, he was eclipsed by James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston and Toni Morrison.

In 1948, activist and writer James Baldwin wrote an essay, Everybody's Protest Novel, arguing that Wright compromised his art for the sake of making a political statement. He was 24 at the time and said Wright stripped characters like Bigger Thomas of their humanity.

"One of Baldwin's big criticisms of Native Son is — and Ellison's too — is that Bigger Thomas in some ways isn't really a person. He's kind of a caricature. I've always felt he overstates it to say that the book isn't really art. The criticism from both Ellison and Baldwin is that the book doesn't do nearly enough to make Bigger Thomas into a human being. He's sort of a monster," said Anthony Stewart, an English professor at Bucknell University.

Wright was a mentor and close friend to literary critic Ralph Ellison, best known for his novel, Invisible Man. He encouraged Ellison to write fiction as a career.

Ellison's critique of Native Son was included in an essay published in 1963 called The World and the Jug, looking at race in literature.

"Wright began with the ideological proposition that what whites think of the Negro's reality is more important than what Negroes themselves know it to be," Ellison wrote of the controversial book.

"Wright could imagine Bigger, but Bigger could not possibly have imagined Richard Wright. Wright saw to that."

According to Princeton University professor Imani Perry, Baldwin and Ellison critiquing Wright's work is par for the course to make room for their own work.

"It was very much a moment in which there could only be one Black literary star at a time. And so that was sort of a kind of literary patricide."

She argues the controversy that ensued from the barrage of criticism came at a cost by neglecting to appreciate the genuine talent Wright had.

"So many of us have failed to see how extraordinary Wright was as a writer and as an intellectual, irrespective of whether one agreed with his political takes on Black Life."

But the accusation against Wright has stood for decades — that his fiction portrayed Black people as defenseless targets, helplessly stunted and distorted by forces beyond their control, robbed of any agency — that it was a failure of his imagination to not depict the humanity, beauty, richness and resilience of Black people's inner lives.

A changed legacy

Wright's work is often not taught in universities or discussed much in general. But that changed when The Man Who Lived Underground, his follow-up novel to Native Son, was published in 2021.

The novel is very different from Native Son. Experimental, dreamlike and surrealist, with a Black protagonist named Fred Daniels who is almost nothing like Bigger Thomas, and yet more victimized by racism.

"Fred Daniels is an innocent, churchgoing, God-fearing man with a wife who has a child with a baby on the way and who's falsely accused of murdering someone and is put in prison because of it. He's the polar opposite of Bigger Thomas," said Eubanks.

In The Man Who Lived Underground, Fred Daniels is randomly picked up by police after a brutal double murder. He's tortured until he confesses to a crime he didn't commit. Eventually, Daniels manages to escape, slipping through an open manhole cover and beginning a new life in the world beneath the pavement and buildings of the city. Daniels learns to navigate his way through the underground and finds burrows into several different buildings and businesses. At one of them, he witnesses someone being falsely accused of a crime and being beaten — by the same police who accused and beat him. When he goes back aboveground to tell those police what he's seen and learned underground, he's shot and killed by one of them.

For Glaude, this newly published book is a searing take on the kind of anxiety that resonates in the U.S.

"It is an unflinching account of the effects, the horror of white supremacist life. Period," said Glaude.

"He's getting at the heart of who we take ourselves to be in the world we've built. And that's not reducible to just simply white violence exacted on black folk or black folk turning into monsters because of white. No, no, no. It's something much bigger."

The Man Who Lived Underground may have been too much for 1942 — but 2021 seemed to be a time it was written for.

"I think the reissue of The Man Who Lived Underground was so important in a moment in which cops are still killing us. To make clear that what is happening today isn't new, it doesn't mean that you have to agree with Wright's aesthetic. But the point is that what he was trying to account for still needs an accounting," said Glaude.

And it's not just what Wright accounted for that's important. According to Anthony Stewart, it's also what he made possible.

"What Wright makes possible is for people to see an African-American intellectual living in their midst... a well-known African-American in the public eye and not for being an entertainer or an athlete."

Stewart argues that it was easier for people to see a Black baseball player like Jackie Robinson Right than to see a prominent Black intellectual.

"This is an unusual thing, a really unusual thing. And so what Wright makes possible is, you know, Wright makes Baldwin possible. Wright makes Ellison possible."

Guests in this episode:

Ralph Eubanks is a literary scholar, professor, journalist and author of several books, including, Ever Is a Long Time: A Journey Into Mississippi's Dark Past.

Eddie Glaude is an award-winning author, James S. McDonnell Distinguished University professor of African American Studies and Chair of the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University.

Imani Perry is a Hughes-Rogers professor of African American Studies at Princeton University and contributing writer at The Atlantic magazine.

Anthony Stewart is a Canadian-American professor of English at Bucknell University and expert in 20th Century Black American literature.

*This episode was produced by Chris Wodskou.