UNB law school urged to shed name linked to slavery, residential school

Ludlow Hall named after judge who supported slavery and keeping Indigenous children away from families

The name Ludlow Hall, spread in bold letters over the entrance to the University of New Brunswick law school, is an unsettling, hurtful sight for some students who have to see it every day.

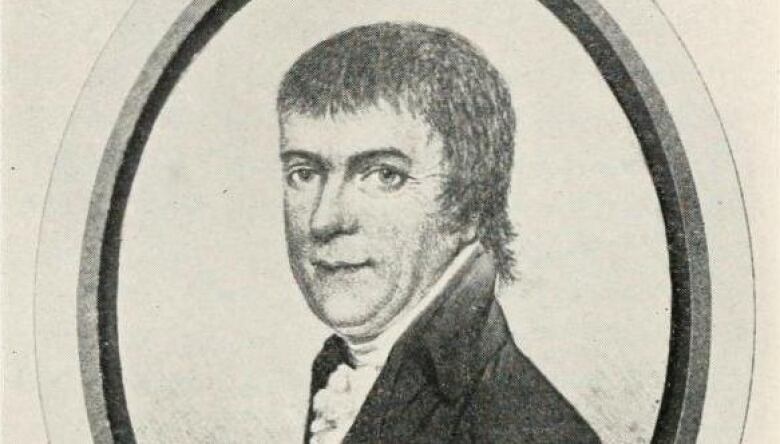

George Duncan Ludlow, a Loyalist and the first chief justice of New Brunswick, sided with slave owners in the colony and also supported an early residential school for Indigenous children.

Karen McGill, who graduates in October from the law school in Fredericton and is a member of the Manitoba Metis Federation, said she found it difficult to have to see the name on her way to class.

"It's right there," she said. "You have to walk underneath his name, you know, to come into the building.

"I'm taught that my ancestors walk with me, and I wondered, 'Do they walk into a building that honours, you know, someone like Ludlow?'"

'Partisan of slavery'

McGill wants the name of the building changed.

The first problematic part of Ludlow's history is his relation to slavery.

There had been slaves in the region since the first French settlers. After the American Revolution, many black people travelled to the Maritimes, including some who were free and some who were slaves.

Historians are divided over whether Ludlow himself owned slaves. Records at the time the Loyalists arrived in New Brunswick in the early 1780s aren't reliable. On the logs for ships that brought Loyalists north, for instance, slaves could have been listed as "servants."

Writing in a 1995 issue of the UNB Law Journal, historian Barry Cahill said Ludlow's brother was a slave owner, as many of the Loyalists from New York were, including Ludlow, "the leading judicial partisan of slavery in New Brunswick."

In Ludlow's day, New Brunswick had no law regarding slavery, either banning it or permitting it, and it was essentially a legal grey area.

In 1800, the Supreme Court of New Brunswick had a chance to outlaw slavery but instead allowed it to carry on.

The case involved Caleb Jones, who had come to the colony via Maryland, bringing slaves with him. He petitioned the court to have one of his slaves, known as both Ann and Nancy and living away from his property, returned to him.

In a split decision after a two-day trial, Ludlow sided with the slave owner.

The effect of the four-man court's decision was to send Nancy, who had been ordered to appear for the hearing, back to Jones.

Residential schools

Earlier, Ludlow had sat on the board of a precursor of residential schools.

In the mid-1790s, a day school for Indigenous children opened in Sussex Vale, near Sussex. While children did not live at the school, they were not allowed to live with their parents either, according to historian Judith Fingard.

Instead, the children were expected to live with white "apprentice families," where they could learn a trade if they were boys or housekeeping if they were girls.

The idea was that the children would become an example to other Indigenous people and inspire them to give up their traditional way of life.

Ludlow was such a supporter of the scheme that he resigned in impatience when, 15 years after the school started, children were still being allowed to return at night to their parents.

When McGill started at the UNB law school in 2016, she was aware of Ludlow's connection to slavery, she said. That was enough for her to want the building renamed.

When she learned of his connection to the Sussex Vale school, she became even more convinced of the need for change.

On its website, the law school acknowledges Ludlow's role in the 1800 slavery case but not his alleged ownership of slaves or his connection to an early residential school.

McGill, who only recently felt comfortable about speaking out on the issue, said the university knows enough about Ludlow to know what a problem his history is for students.

"It says to me that the university doesn't care about history and about truth and about reconciliation," she said.

"It made me feel very unwelcome."

Why Ludlow?

McGill said Ludlow has little actual connection to the university anyway.

In fact, the connection only goes back 51 years.

The law school was originally called the King's College law school and was only integrated into the university in 1923. It was located in Saint John until it was moved to Fredericton in 1959, at first into Somerville House on Waterloo Row.

Ludlow Hall didn't open on the UNB campus until Oct. 7, 1968. It's unclear when Ludlow's link to slavery became common knowledge, but it wasn't mentioned in the Daily Gleaner article covering the opening of the building.

McGill said Ludlow's story and his tenuous relationship with the university make UNB's lack of action surprising.

"His accomplishments are just no longer that impressive, and then when you add in the truth of his furtherance of slavery, genocide and basically human trafficking, you know, a much darker picture emerges," she said.

"I definitely want every law student and lawyer in this province to know about George Duncan Ludlow, but not to look up to him."

In a statement to CBC News, the university's Law Students Society said it was aware the Ludlow name was a concern among students but stopped short of calling for a change. Instead, the society called for a conversation about the issue.

'An opportunity'

"There is opportunity now to discuss the ugliness of George Ludlow's history — a history which does not serve to represent rights and interests of current students," said Molly Murphy, president of the society.

"As the student body becomes increasingly diverse, the administration should be ready to respond appropriately to suggestions and proposals for change."

CBC News sought an interview with someone from the UNB administration but no one was made available.

But in an email statement, law dean John Kleefeld acknowledged society is becoming more aware of "our colonial past" and suggested a change might be considered.

"UNB is also open to acknowledge New Brunswick's colonial history, and its current administration has expressed a willingness to hear recommendations from the faculty of law on the law school's name," said Kleefeld.