'It's not the dream they had': Futures shattered by overdose-related brain damage

But according to Dr. Delbert Dorscheid, a critical care doctor at St. Paul's Hospital in downtown Vancouver, the night before his parents arrived, the student 'went out partying with his buddies, and got into some fentanyl.'

Dorscheid would treat the young man in the ICU after an overdose that left him with irreparable brain damage. When he met the young man's parents, he watched them come to grips with the fact that their son, as they knew him, was gone.

"His poor mom would pace. Whenever she touched his hand she knew he wasn't there," said Dorscheid, describing what's become a familiar scene in his ICU.

"These are young, beautiful people, you know. You see their moms and dads and their siblings come at bedside and they're talking to them and they can't understand...what has happened. They see the body and there's no trauma. There's nothing that would tell you that they've been injured to the point where they're never going to come back."

Dorscheid told Dr. Brian Goldman, host of White Coat, Black Art, that the patient left the hospital "without meaningful brain function."

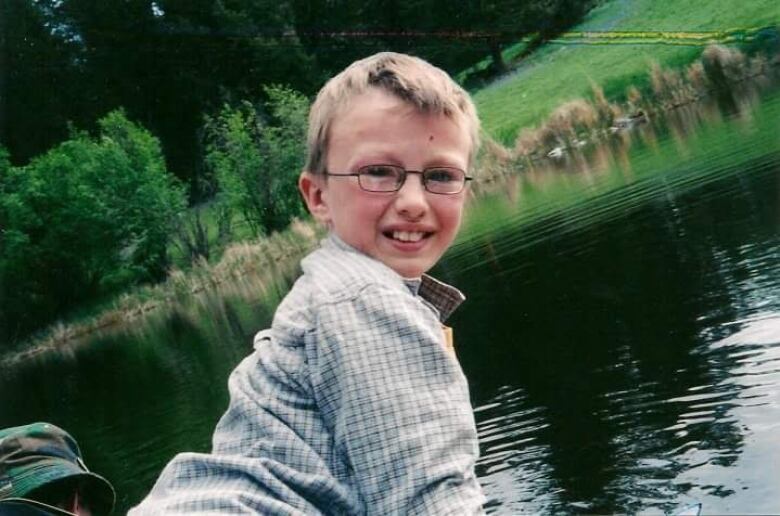

The story is not isolated. Last week in Part One of the series After the Overdose, White Coat, Black Art told the story of 24-year-old Dayton Wilson, who accidentally overdosed on fentanyl in August, 2016, and now lives with a permanent brain injury.

"It was really terrifying," Valerie said, recalling his first few days in hospital.. "Over the next few days,he lost the ability to walk at all. We had to wheelchair him to the bathroom. We had to be in the bathroom with him or he would fall over just trying to urinate."

Dorscheid said he began to see patients like Datyon, who 'lingered' in the ICU' and who showed signs of brain injury about five years ago, and now has as many as four patients like them in beds 'at all times'.

Lack of data a problem

A spokesperson for Vancouver Coastal Health confirmed that tracking such patients is challenging because there is no easy way of identifying those who have brain injury after overdose. The health authority says it intends to work with specialists to develop case definitions for people who suffer brain injuries after overdose, and to better track people at risk of overdose death.

Dorscheid said the lack of data makes it difficult to provide appropriate services for those affected.

"I think that it allows those people looking at the data to kind of turn their backs to the ultimate problem. Someone that unfortunately succumbs or dies to a final overdose, their problem is kind of over…And that's the numbers that get reported in the media. But the bigger problem are those that remain with either some level of disability or some profound level of disability and needing long-term care at the end of the day," he said.

Many of the patients have lost contact with family, and often there is no one to make decisions about a patient's future, leaving a public trustee to step in when it becomes clear a patient will not recover, he said.

Other patients recover, but not enough to live independently, so they are moved to long-term care.

Parents hold out hope

That creates challenges for staff, patients, and their families, according to Rae Johnson, the site leader at Holy Family Hospital, a long-term care facility which is part of Providence Health Care in Vancouver.

"We had a lady move last week who was 103. Our youngest resident here is 33. So I always use the analogy of what music would you like to play for that age group, that age range?" Johnson told Dr. Brian Goldman.

She said staff are used to dealing with children of patients, but are now faced with parents who still are holding out hope that their child might recover after their overdose-related brain injury.

"It's really difficult transition when the medical team around the person says they have plateaued. They do require residential care. And often the family member will come in wanting a high level of service in terms of physiotherapy and other therapies that isn't provided in long-term care and then they feel very helpless," she said.

The younger brain-injured patients include a young woman 'who requires care to turn in bed because she presents like a person who's had a stroke,' Johnson said.

Not the life they imagined

"There are residents who, it's hard to tell what they're aware of. They have limited language skills remaining," she said, adding that one woman is only able to express her needs through screaming, which challenges the staff.

Meanwhile, parents struggle to accept the new circumstances that are 'not the life they imagined for their child.'

Valerie Wilson said while she's grateful her son Dayton survived, she's come to realize "he's not the son I had." Once a free spirit, he's now cautious and unable to play music as he once did.

Of his own struggles, Dayton said, "I could do it all so well before. And then after, it's like, 'Nope. Now you're not going to do any of it well."

Johnson said parents grapple with planning for a future that might see their child in long-term care for decades, although some eventually move their children home after they retire or renovate their houses to accommodate the children.

B.C has a Senior's Advocate which oversees elderly patients, Johnson said, but explained that the younger residents "aren't a part of that mandate, although they are in the facilities."

Still, Johnson believes that there is a "growing sense" that all patients who overdose and suffer brain impairment need more help.

"Beyond the folks that come into care, there are folks that are less impaired and able to be discharged but have some brain injury. And so how are they going to be supported to prevent the next overdose?....How can we support them differently?"