What a 16th-century plague survival guide has in common with COVID-19 advice

Italian physician Quinto Tiberio Angelerio drafted 57 rules for staving off the disease

It's been a struggle for some people to keep six feet apart and stay home as much as possible during the COVID-19 pandemic. But a 16th-century manual on how to survive the bubonic plague shows it was just as challenging for people to follow those public health measures during the Renaissance.

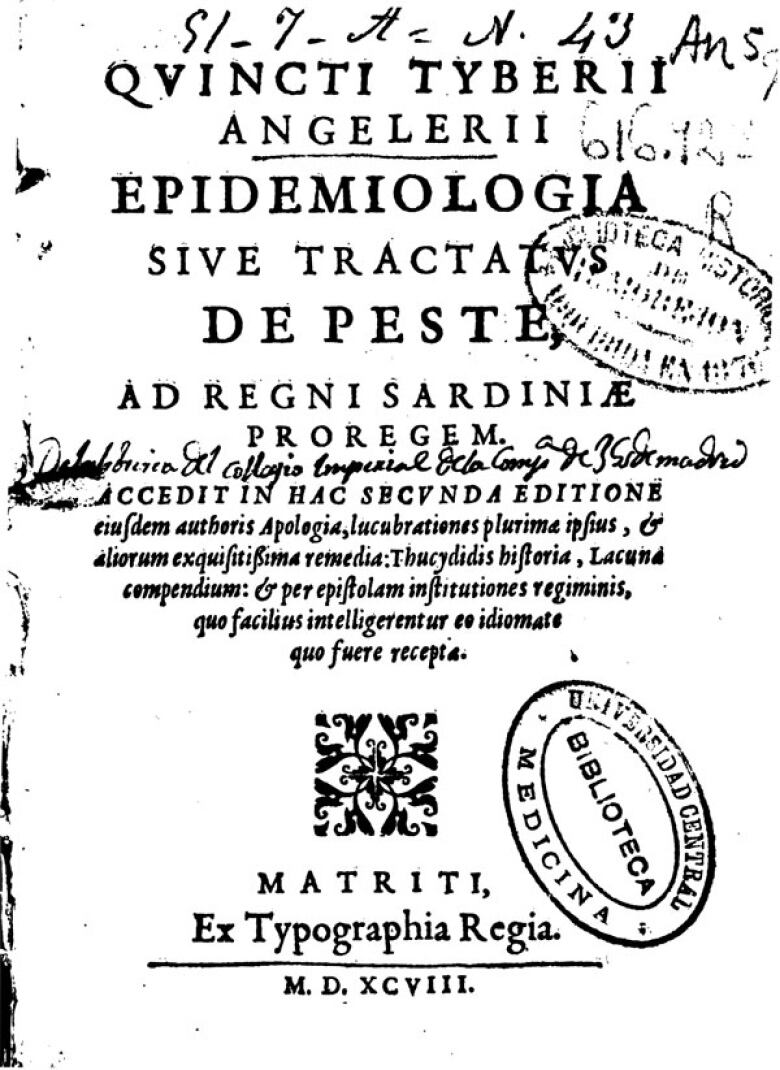

The manual, called the Epidemiology or Treatise on Plague, was written by Italian physician Quinto Tiberio Angelerio in 1588. He wrote the manual six years after an outbreak of the bubonic plague in the Italian port town of Alghero, on the island of Sardinia. It's believed the disease was carried over by boat from France.

John Henderson, a professor of Italian Renaissance history at Birkbeck, University of London in the U.K., said the text is part of a long tradition of "plague tracts" dating back to the Black Death of 1348. Doctors often wrote tracts like this during epidemics to provide governments and individuals with advice on how to steer through future health crises.

Henderson, who also authored Florence Under Siege: Surviving Plague in an Early Modern City, spoke with The Current's Matt Galloway about historic plague policies and practices. Here is part of their conversation.

This tract, the booklet, lays out ... 57 rules. What are some of them that would be familiar to us now in the midst of the pandemic that we're living through?

You can really divide them into two main sections. One is at city level. So therefore, once plague had broken out ... they carefully controlled anybody entering the town. They then divided up the city into 10 zones, each of which had a health officer in charge to direct the campaign against plague.

More broadly, regulations were against groups gathering together…. So, for example, people were not supposed to play games outside or attend meetings.

Once plague victims were identified, they were either treated at home or taken to separate plague hospitals. And then their contacts were either shut up in their apartments or taken to separate quarantine centres.

Those houses where somebody had been sick or died were then disinfected … and the mattresses and textiles within it were taken out and burned. And then surfaces were washed with vinegar, and the clothes of the sick were sterilized through heat in the stove. And in fact, our author [Quinto Tiberio Angelerio] is said to be the first person to have recommended dry heat to disinfect clothes.

When the house was locked up, a red cross was painted on the front door and nobody was allowed to leave. But the inhabitants inside were fed. And indeed, during the epidemic, medical treatment and food was provided free to the poor. So there was a combination, if you like, of both institutional and also house quarantining of the sick and their contacts.

What about this ... rule that if you went out you needed to have some sort of six-foot cane so that you'd stay away from other people? What was going on there?

I think it was a recognition that the plague could be spread through the air ... in the way that we see with COVID now. I mean, it wasn't something that was necessarily true. Bubonic plague ... was spread by infected fleas from rats.

But the idea of … carrying the cane was simply to indicate the distance that people should maintain from each other, because, obviously, they thought if somebody breathed out air, which was from a sick body, then people would get plague.

We see now pushback in some corners and resistance to public health measures. What was the reaction to the measures then? I mean … if they found that these, you know, regulations were too onerous, how were they going about violating them?

There's a lot of similarity between the past and present in that sense, that I mean, most people appear to have obeyed the rules. But there are lots of … examples of people leaving their houses and being prosecuted.

[My] book is about plague in Florence during the last epidemic, when it hit the city in the year 1630-31…. And I was fortunate enough to come across, in the archive, over 550 court cases against people breaking the law.

There's an example of a lady in November 1630 who leaves her house in pursuit of a chicken, which has escaped from her house. And she sort of says ... to the court when she's taken up before the judge, "I rushed out in order to find this chicken which has escaped." And she'd been arrested. And I mean, when the judge heard her story … he was clearly full of compassion. [He] just let her go.

I think this is something that's not often reflected in the period of the time — sort of the ideas of loneliness as we've all experienced over the last year. There's an example of a lady … who had moved to a friend's house despite having been told she had to stay in her own one ... and when she'd been arrested for leaving her locked up house, she said that she didn't want to remain alone at [her] house. [She said], "I went to stay in this house … thinking I'd not done anything wrong. And I found myself in the house of good people."

There are also examples of sociability which do break the law much more significantly. So people, for example, going to taverns, people playing cards. And obviously this was, you know, [a] serious time during lockdown, so this was discouraged.

There are even cases of people walking along the top of roofs, along terraced houses in order to visit friends and have a party and play guitar and so on.

Are there things that you hope people would take away from the plagues of the past in the situation that they find themselves in now?

In terms of government policy, the necessity to take action quickly. I mean, that didn't always actually have as much effect as they'd wanted in the case of plague.

I was very struck by the compassionate nature of attitudes towards the poorer members of society — that they created sort of public health works in order to provide work for people during the plague. They provided free food during total quarantine in the city and even allowed some employees to continue working in the textile industry.

The other thing which I've been very struck [by] over the last year as well is … people's compassion and how it's arisen in this period.

The enormous number of volunteers who staffed hospitals and who staffed sort of isolation hospitals and also went around doing sort of sanitary surveys and so on. In other words, all those people in the front line against epidemics, as in the case of public health workers today.

Written by Kirsten Fenn. Produced by Samira Mohyeddin. Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.