These authors dedicated a year to self-improvement. Here's what they learned

From Fitbits to so-called smart drugs enhancing brain function to articles on how to break bad habits, we live in an age of self-improvement.

It's a burgeoning, profitable, multi-billion dollar industry that can at times lead to a an unhealthy obsession

Carl Cederstrom and Andre Spicer spent a year immersing themselves in the business of self-improvement.

"We'd been interested in self-improvement and optimization culture for a relatively long time and also wrote our previous book on the topic and people pointed out, when that book came out, The Wellness Syndrome, did we have any first-hand experiences of this ourselves?" Cederstrom tells The Current's Anna Maria Tremonti.

"And the truth was that we didn't really have any experiences at all."

Each month dedicated to a specific pursuit

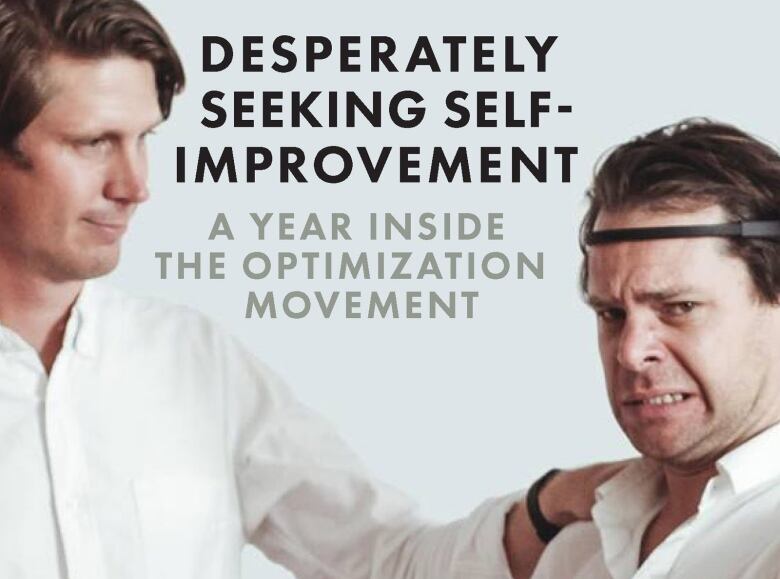

In their book, Desperately Seeking Self-Improvement: A Year Inside The Optimization Movement, professor Spicer and associate professor Cederstrom dedicated each month to a specific pursuit.

In July, they focused on pleasure.

"I'd been a vegetarian for 16 years and I picked up eating meat again — some of which was good, and some of it was bad," Spicer recalls of that month.

"And then I went on an all junk food diet and spent my time playing video games."

"Many of my friends would find that deeply pleasurable. I found it rather unpleasurable," Spicer says.

Attention experiment

In the month of November dedicated to attention, Spicer approached talking about body image and judgement in a public way, by stripping down to his underwear on public transit.

Cederstrom says we now live in an age where self-improvement is synonymous with being morally good.

"We could really see how self-improvement is something we all take for granted. Why would you not want to become a better person?"

This is how society is organized today, Cederstrom says, "around principles of competition and a very individualistic notion of doing your best."

'This was all sort of meaningless'

"In some ways, we began to realize that maybe this was all sort of meaningless in some ways. Like it all was just pointing at the absurdity of self-help," Spicer tells Tremonti.

"As soon as you kind of stopped trying to improve yourself, there's this kind of return to the way you were almost beforehand — the kind of old habits kicks back in."

Listen to the full conversation above.

This segment was produced by Calgary network producer Michael O'Halloran.