Why listening to your old faves can be such an effective antidote to stress

The brain releases series of hormones linked to mood and feelings of comfort and trust

Hearing just the first few bars of a song you loved as a teen can send you right back to a high school dance or a first date or even just your childhood bedroom, where you promised you were doing your homework when you were actually reading the liner notes of your favourite album.

Or maybe that tune puts you back in the space of your first job or reminds you of a friend you lost touch with decades ago as you sing along with the words you somehow still remember decades later.

It's all about nostalgia: that bittersweet longing for something from one's own past.

According to one expert on the subject, nostalgia has been big during the pandemic. And for good reason.

"The No. 1 function that nostalgia appears to serve is that it's soothing," said Krystine Batcho, a psychology professor at Lemoyne College in Syracuse, N.Y., who has studied the subject since the early 1990s. She says generating feelings of nostalgia can be a comfort and act as an antidote to stress.

"When the lockdowns happened with the pandemic, a lot of things kicked into gear," she said. "People had to change their lifestyle habits. People shopped differently... All kinds of things about ordinary life changed as the pandemic became worse and worse."

'Nostalgic-themed playlists' surged

One of the things people turned to for comfort was music. Familiar music.

"It does evoke certain memories or people that I may not have thought of for a very long time," said Brandon Lim, a musician and film programmer from Toronto. "Or a memory that just kind of came loose, that I haven't thought of for 20 years."

In April 2020, during the first pandemic lockdown period, Spotify reported a 54 per cent increase in listeners making "nostalgic-themed playlists," along with an increased share of listening to music from the 1950s, '60s, '70s and '80s.

A European researcher who analyzed data from almost 17 trillion plays of songs on Spotify in six European countries found "evidence of increasing nostalgia consumption of music caused by the pandemic," in the period immediately after the pandemic was declared in March 2020.

But what's nostalgic to one person may not be for another. It's often about what you were listening to when you were growing up.

"People are most nostalgic for the music that was around in popular circles when they were young adults," Batcho said. "Either late adolescence or early adulthood."

Connection to our earlier selves

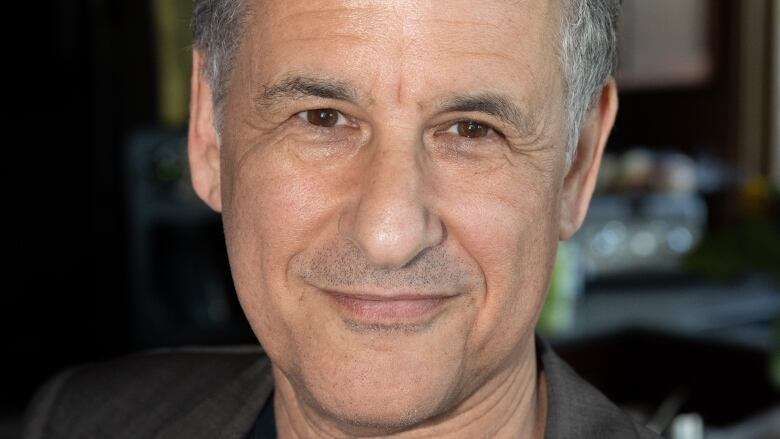

Neuroscientist Daniel Levitin, who has spent years studying music's effect on the brain, agrees it's all about those teenage years.

"The stuff you learn between 10 and 20 is special," he said in an interview with The Sunday Magazine.

"If it's music you like and that you grew up liking... there's this sense of comfort. And it brings us to a connection with our earlier selves that unites our teenage selves with our current selves. And it does so in a way that helps you to feel the continuity of your life."

LISTEN | Nevermind at 30: A classic, but is it 'classic rock?'

Lim, who is 38, says some of the music that makes him feel most nostalgic for his younger days is music he didn't even like at the time.

"I may not have listened to it at that time, but it might remind me of, oh, you know, my friend Kevin, who was a huge Smashing Pumpkins fan," he said. "I haven't seen him in over 10 years, but we used to listen to that Smashing Pumpkins CD all the time, driving around in his car."

Music and the brain

In his book This Is Your Brain on Music, Levitin describes the physiological impact music has on a person.

"You listen to that piece of music that's comforting and your brain releases prolactin, the same soothing and comforting hormone that's released when mothers nurse their infants," he said.

"It can release or modulate levels of dopamine and serotonin, which are responsible for mood and pleasure. And listening to music you like, particularly if you sing along, can release oxytocin, a hormone associated with increased feelings of trust and bonding."

So why is the music you grew up with so important when it comes to nostalgia? And why can it still feel nostalgic even if your teenage years weren't particularly great?

"When you're entering young adulthood, there's an idealism and hope that you're going to chase after," said Batcho. "Accomplishing your goals in life, your dreams, your aspirations. That is so exciting and it's so special."

Lim says the music doesn't even need to conjure a specific moment.

"I sometimes find myself nostalgic for songs from that period just because it can sometimes be connected to the really early childhood memories that you might not even necessarily remember — the time and place of the memory, or exactly what happened. But it just connects you to a sense of being young and sort of just having your whole future ahead of you."

Connecting people to people

Batcho says even if one's childhood was unhappy, that transition period to adulthood can represent moving forward and leaving unhappy times behind.

"You could argue that to some extent, it's nostalgia for what might have been. It's a nostalgia for the ideals that someone was perhaps cheated out of." Remember, she says, that nostalgia is bittersweet, not just sweet.

Of course, you can also feel nostalgic about a song that's not from that key late-teen or early-adulthood time period — a song that reminds you of your favourite team winning a championship, or your wedding day or your kid because he or she listened to it incessantly just a few years ago.

"There are other types of powerful memories associated with music because the music gets attached to other things that people care about," Batcho said. "It connects people to other people."

For Lim, one such song is Everybody Wants to Rule the World by Tears for Fears. He and his brother used to jump on the bed together when they heard it.

"Every time that song comes on, I can just actually feel time sort of slow down around me, and I can just feel myself just becoming so lost in that feeling of ... experiencing nothing but that song and not really having a care in the world."

Levitin says that in these moments, the brain is creating a connection between "This is who I am now" and "This is who I was before," which he says is "a powerful centring mechanism."

"People often say to me, 'Oh, this song came [on] that I hadn't heard of in a long time... and I suddenly felt at peace.'"

Lim says sometimes that song gets even better with age.

"It almost becomes like this cumulative thing where every time you hear it, it just gains more power and becomes that much more evocative as you get older."

Written by Stephanie Hogan. Interviews by Stephanie Hogan and Peter Mitton.