When the environment was not a partisan issue

Few issues in North American politics are more fiercely partisan than climate change.

Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper's Conservative government was internationally notorious for being a laggard on climate action. Likewise, Conservative governments in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and New Brunswick have made common cause with Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer in opposing carbon taxes.

But the environment, let alone climate change, wasn't always an ideological flash point. It wasn't so long ago that former prime minister Brian Mulroney's Progressive Conservative government was a global leader on the environment.

In 1987, Mulroney hosted world leaders in Montreal to get them to drastically cut the use of ozone-destroying CFCs — chlorofluorocarbons. More than 40 countries signed that pledge, including conservative icons like former U.S. president Ronald Reagan and former U.K. prime minister Margaret Thatcher.

A year later, in 1988, Mulroney hosted the landmark World Climate Change Conference in Toronto, a conference that has been credited with officially putting climate change on the global agenda.

[We] did not see the environment and the economy as hostile to each other ... We saw opportunities through environmentalism to save and create jobs, and generally to enhance the lot of all Canadians.- Tom McMillan, environment minister under Brian Mulroney

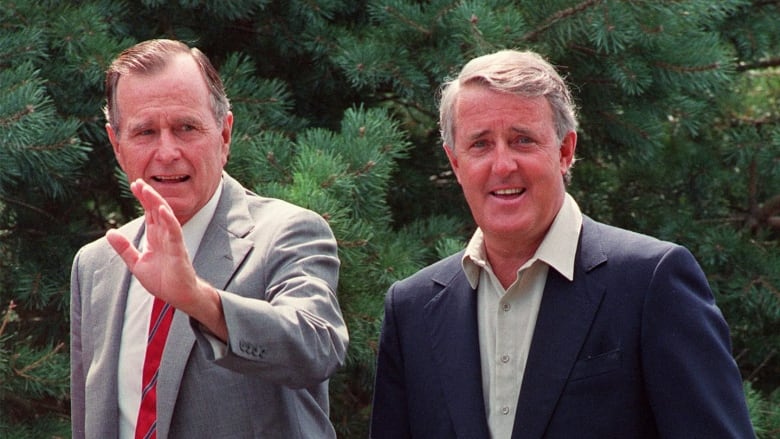

Then, in 1991, Mulroney signed the Canada-United States Air Quality Agreement with President George H. W. Bush to reduce pollution that causes acid rain.

For all of that, in 2006, Mulroney was named the greenest prime minister in Canadian history.

But much has changed since then. Serious action on climate change is the domain of the left in Canada, while conservative parties downplay its importance as an issue.

Tom McMillan was the environment minister under Brian Mulroney, from 1985 to 1988. He's the author of a book called Not My Party: The Rise and Fall of Canadian Tories, from Robert Stanfield to Stephen Harper.

McMillan spoke to The Sunday Edition's Michael Enright about his record on climate change and the need for bipartisan compromise in resolving environmental issues.

Here is part of their conversation.

Take me back to those weeks, the months leading up to the Montreal Protocol. What compelled your government and other countries to jump into action so quickly about the ozone layer?

The ozone layer is all that protects human population and the planet from the most lethal of the sun's cancer-causing rays. So it was essentially the scientists who were telling us that the ozone layer was depleting and was being assaulted by human behaviours, and in particular substances and consumer products like air conditioning and refrigeration. We couldn't avoid the science, we couldn't avoid the facts and so we couldn't avoid seeking a solution, and that's exactly what we did.

How did conservatives generally view environmental issues of the day during your time? Was it ideological? Was it scientific? Was it partisan?

It wasn't a common front across the different conservative parties around the world. Initially, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan could hardly have been described at the time or sense as environmentalists or in the vanguard of environmental leadership. But in the case of Reagan, for example, industry was telling the Reagan administration that these substances were going to have to go. And DuPont, for example, the great petrochemical company, saw a huge opportunity, as did their fellow corporate giants, to produce the substances that would would have to be created to replace those that were going to be outlawed under the Montreal Protocol. So it was the combination of companies, corporations, the private sector, if you will, seeing the writing on the wall and government responding to that kind of pressure. And, I have to say, some inspired political leadership in some quarters, but not all Reagan and Thatcher. They came on side belatedly, begrudgingly, but inevitably.

What changed between Brian Mulroney and the government you were part of and Stephen Harper that made the environment and climate change an issue that conservatives didn't feel too much urgency about?

I think it has an awful lot to do with leadership. Brian Mulroney was a very different human being from Stephen Harper and the party that he led, the Progressive Conservative Party, with the emphasis on progressive, was very different from that which was formed in 2003 through a marriage between the then Conservative Party and a Canadian Reform Conservative Alliance, which became the new Conservative Party. That latter party was ideologically different, it was not at all in the grand Tory tradition from Sir John A. Macdonald right through to Mulroney. And, as you pointed out rightly, it was not just indifferent to environmental causes, but indeed hostile to them.

- How climate change denial is changing amid global protests

- What happened when environmental activist Greta Thunberg met Prime Minister Justin Trudeau

- How Toronto participated in the climate strike

In Canada, as you know, the debate about climate change and the environment and so on is cleaning up the environment versus jobs and how one might rule out the other. People are worried about carbon taxes, their jobs, income and all that. What would a Progressive Conservative response be to the current conundrum?

At that time [we] did not see the environment and the economy as hostile to each other. They were complementary. We embraced environmental principles. We saw opportunities through environmentalism to save and create jobs, and generally to enhance the lot of all Canadians. So the two, environmentalism and economics, are not at odds. At no time in human history has that been truer now with the move towards renewable sources of energy.

Unless we have that pragmatic approach which he embraces, everyone — left, right, centre, the private sector and the total population—then we're doomed.- Tom McMillan

Do you think that your government's policies in the environment were successful because they came from the right of the political spectrum rather than the left?

No, not at all. The environment is not the preserve of the left or the right. The environment has to be a cause embraced by everyone. That's probably why we were successful. We didn't allow ourselves to be characterized as ideologues or zealots or missionaries. We were problem-solvers. Brian Mulroney is not an extremist. He's a pragmatist, and that's the kind of government he led. It's the kind of approach that is needed now to deal with the No. 1 existential threat to the planet and the human population: climate change. And unless we have that pragmatic approach which he embraces, everyone — left, right, centre, the private sector and the total population — then we're doomed.

This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity. Click 'listen' above to hear the full interview.