When our magnetic field flips, say goodbye to modern life

Scientists say the magnetic North Pole will eventually switch places with the South Pole, with potentially apocalyptic results.

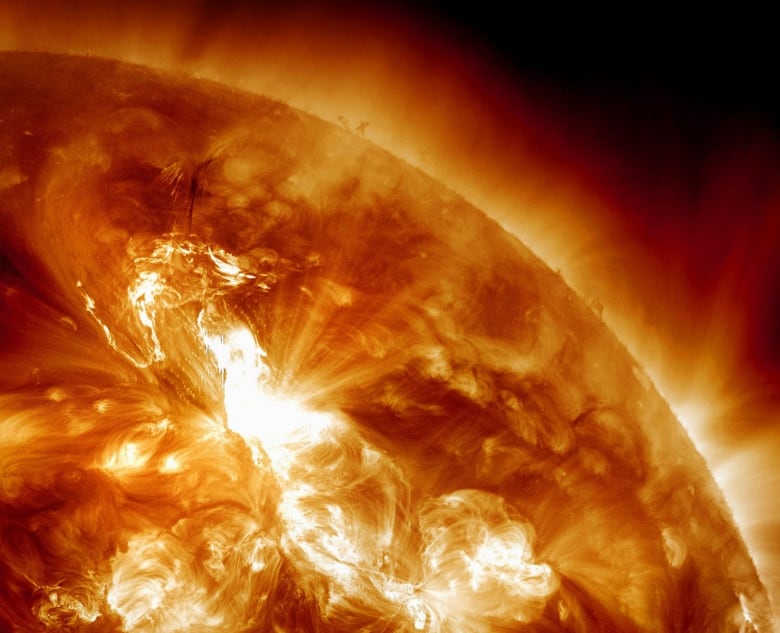

The Earth's magnetic field is enormously important. It's a vital shield that protects us — and our technological society — from dangerous radiation from the Sun and deep space that would otherwise scorch us and blow our electrical system and electronics to smithereens.

In her new book, The Spinning Magnet: The Electromagnetic Force that Created the Modern World and Could Destroy It, Canadian journalist Alanna Mitchell looks at this disaster scenario. She talks to scientists who are investigating the vital role our magnetic field plays, and why they're concerned about how our planet will lose protection from solar radiation storms that will wipe out all electromagnetic technology. The result would be no satellites, no internet, no smartphones and maybe no power grid at all.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Bob McDonald: Now you start this book in a canvas tent in the late Arctic summer. What brought you up there?

Alanna Mitchell: Oh I was in search of Franklin, Sir John Franklin. He was part of what's known as the magnetic crusade. Really it was the first international collaboration of science and they were trying to figure out you know how the magnetic field worked.

BM: Trying to figure out where magnetic north is?

AM: That was part of it. But they were also just trying to figure out how they could be sure that their compass readings were correct and they never cracked it.

BM: What did you see when you were up there?

AM: Well, what I saw was the aurora borealis. So I was in my canvas tent actually on a muskox skin up in the far North on King William Island and the aurora borealis began. And you know it's just this glorious dance of colour. It just draws you in, you know? You just you just feel extraordinarily alive to look at this. And I started to wonder what is that?

BM: How then do the aurora relate to what's going on deep within the Earth?

AM: Well, the aurora are disturbances in our Earth's magnetic field that are caused by disturbances in the sun's magnetic field. And occasionally they interact and that causes all this turbulence in our atmosphere which we perceive as these dancing lights in the atmosphere. But the fact that we have a magnetic field at all is the result of these torturous machinations in the outer molten liquid core of our Earth. It's those machinations, this shedding of heat from the solid core that create this great magnetic shield that protects our planet from solar radiation.

BM: Now it took quite a while for scientists to figure that out that the Earth was generating a magnetic field and producing this what they called a strange force that pulled the compass. Tell me a little bit about that journey of discovery.

AM: What fascinated them was magnetism. But it seemed to be the great conundrum of various ages and electricity, which is of course connected [to magnetism]. The electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental forces of the universe. But electricity was seen as a source sort of poor cousin that was shuffled off into the corner until a Danish scientist did an experiment in 1820 that proved that they were physically connected. And then the entire thing just changed.

BM: Well you've spent a lot of time in your book sort of talking about magnetism, but you also talk about the switching of the magnetic field. So tell me about that.

AM: Well that was again a really long journey. It began in 1905 with a French geophysicist named Bernard Brunhes in …the middle of France. [He] took a took a ride on a horse with his chisels … to the southwest because he heard that there was a seam of terra cotta that was overlain with some volcanic basalt. What he discovered was that at the time the basalt had been laid down by the volcano and then had cooled down again. At that moment, which was as we now know five million years earlier, the poles had been on different sides of the planet than they were in 1905. He did the test and this was just a revolutionary idea. They had no way of explaining this. It was really an assault on this scientific premise of the day about magnetism. It really literally turned everything upside down.

BM:So he said he found that the pole was different five million years ago. Now since then how often have we found out that the Earth's poles actually do switch?

AM: They've switched hundreds of times in general you could say since the last mass extinction 65 million years ago. In general they've switched about every 300,000 years. The last time was 780,000 years ago. Occasionally you know the the poles get very disturbed and they try to switch and don't and then they snap back to where they were before. That's called an excursion and that happened 40,000 years ago.

BM: So does that mean that we're overdue for another reversal?

AM: They're saying we can't say that they're going to reverse just because we think it's time. They're looking at other characteristics of the field to determine whether or not the poles are beginning to reverse.

BM: So what about if another reversal should come along. What are scientists concerned about?

AM: You know the thing that the really the most worried about is how all that extra solar and galactic radiation will affect the electronic and electric structures of the Earth. That's the sort of the first thing on their list. So the shield is generated within this outer liquid metallic core within our planet and it reaches way out into into the magnetosphere surrounding the planet. Think of it like a big octopus. This huge big bulb that goes toward the sun and then comes in at the poles and then streams out behind the planet. That is our field that is generated within our planet and it protects us from all the solar and galactic radiation. It's sort of like a cocoon you know. So when the poles are reversing this field that is such a [protective] shield gets diminished, it wanes, it decays, scientists say down to about 10 per cent of its usual strength. And what that means is that the solar and galactic radiation that is out there in this very turbulent outer space, it's filled with all these incredibly dangerous stuff. And that is able to get closer and closer to the surface of the Earth. It will reach further into the atmosphere and will scotch much of the electric grid and the electronics that our planet currently lies on.

BM: Well tell me about that. What's vulnerable if if our magnetic field gets weakened the radiation from space penetrates deeper in?

AM: Well, you could think of all the interconnected transformers that allow electricity to run from where it's generated to where we we use it. So when you get these magnetic pulses into the atmosphere, it just runs along these lines that we very handily created. We've had examples of this before because there have been what we call solar storms. Really intense episodes when the sun really just chucks off all of this really intense energy.

'We had a huge solar storm that hit the planet in 1859. It's called the Carrington event. The one in 1859 happened just as humanity had laid down all these telegraphic wires and telegraph lines were actually bursting into fire.'- Alanna Mitchell

BM: Well you mentioned in your book in 2012.

AM: This is the thing that just everybody just sat up to attention. Every now and again, and scientists don't know how often, but the last time was in 1859. There is something that's called just a real superstorm. So this is something that is the most extreme type of solar radiation that hits the planet by radiation. I mean pulses of the invisible stuff, not the light. Solar energetic particles that can damage life.

So we had a huge solar storm that hit the planet in 1859. It's called the Carrington event. The one in 1859 happened just as humanity had laid down all these telegraphic wires and telegraph lines were actually bursting into fire. The scientists knew that something like of that Carrington class might come again. And in 2012 it did, except that the sun was turned away from the Earth when that intense intense pulse of energy erupted. Had we been facing the sun at that time, a week or 10 days earlier, that incredibly strong pulse of energy would have struck the Earth. They reckon that power structures would have gone down for decades.

BM: Now one of the scientists that you talked about in the book is Daniel Baker from Boulder, Colo. Tell me about him. Why did you want to meet him?

AM: Well he was one of the people who did the forensic analysis of what happened during the 2012 superstorm that didn't hit the Earth. There was this really beautiful perfect record of what this thing was. And he was one of the people who looked at it and said: 'Oh my goodness. What if it had happened earlier, you know when the sun was facing us?' He's a really strong advocate for doing more space weather analysis and forecasting.

Had we been facing the sun at that time, a week or 10 days earlier, that incredibly strong pulse of energy would have struck the Earth. They reckon that power structures would have gone down for decades.- Alanna Mitchell on 2012's solar storm

BM: What did he suggest could have happened to different parts of the planet had that storminess been in effect?

AM: What they said was that we would have gone back to Victorian times. Pre- electricity times for an extended period of time because we don't have a big stash of transformers that we could just slot into place to replace the ones that have been damaged.

BM: What's his take on if the magnetic poles reverse or if the magnetic field disappears? What does he think it will do to planet Earth?

AM: Well he thinks part of the planet will become uninhabitable.

BM: Really.

AM: Yeah. He thinks that there'll be enough ionizing radiation damaging radiation from the sun, from the galaxy, to make parts of the planet's inhospitable to life.

'Some of the ultraviolet radiation would also be hitting parts of the planet that it doesn't hit now."- Alanna Mitchell

BM: Do you know which part?

AM: No that's the problem. Wouldn't it be great to know. There's no way of predicting what would cause the Earth to become uninhabitable in those places.

BM: What would the radiation do?

AM: Well it would hit the surface of the planet. So you get this ionizing radiation, which is X rays and gamma rays. And actually some of the ultraviolet radiation would also be hitting parts of the planet that it doesn't hit now because … the [protective] ozone layer would be quite stripped away across parts of the Earth. You get all that extra ultraviolet radiation coming down to the planet.

BM: Scorched Earth?

AM: Sounds like in parts. It sounds like science fiction doesn't it? As I started to piece this together, it was just such an extraordinary story because we don't think about it. I mean I don't even think about the magnetic fields, much less that it's so turbulent and so volatile and that it is subject to change.

Daniel Baker is an expert in how the radiation of the sun and outer space interacts with the Earth. So he is saying, 'Well, you know what? We have to look at this. We just simply have to look at it and see what we can do to protect ourselves from harm.'