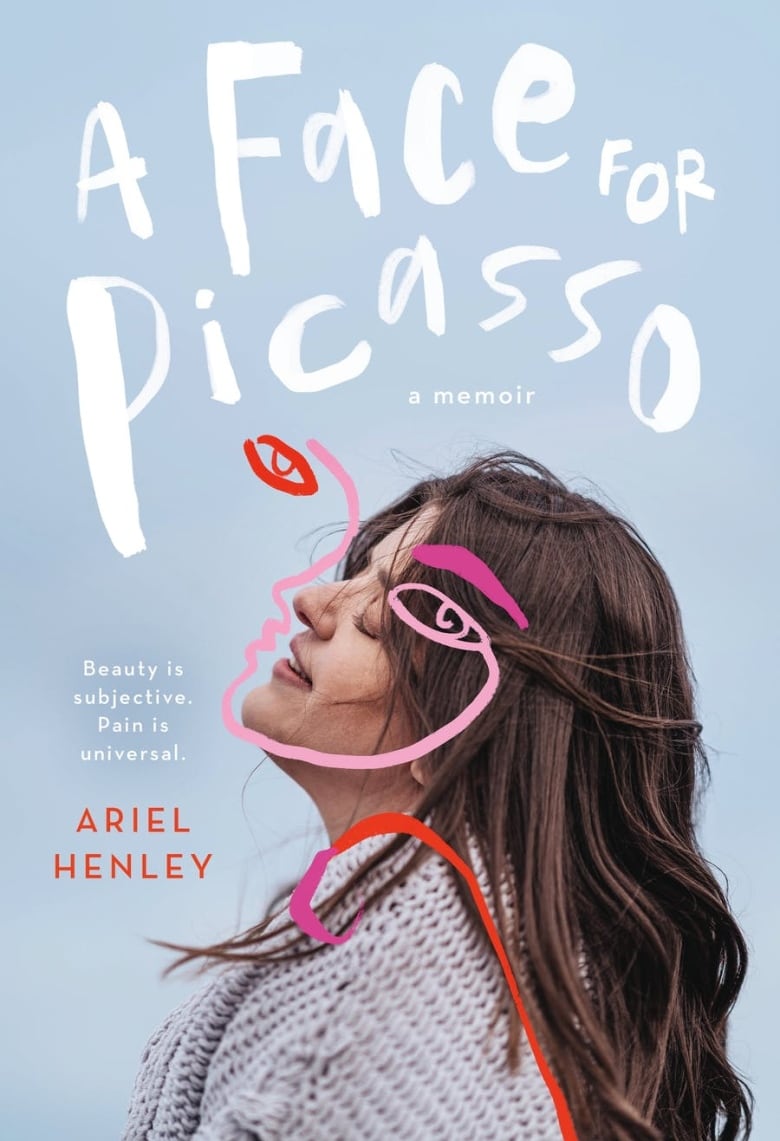

She was told she had a 'face for Picasso.' Now, that stigma fuels her work

'People were trying to tell me that everything about me was wrong just for existing,' says Ariel Henley

*This episode originally aired on September 21, 2021.

From a young age, Ariel Henley got used to being stared at. She knew her face looked different from most people's and endured the constant emotional toll of navigating the world with a facial disfigurement. She now channels that trauma towards ending stigma around physical differences.

"Disfigurement is often seen as being a symbol for everything wrong or sad, and it's a physical representation of everything that people fear," Henley writes in her memoir, A Face for Picasso.

If I listened to those voices telling me I wasn't wanted... I was too hideous to be seen, I would never be able to live my life.- Ariel Henley

Now 30 years old and living in the San Francisco Bay area, Henley's work examines and challenges cultural narratives around facial disfigurements and differences — that the people who live with them are evil, lacking in humanity, or are a genius in some way that is unnatural.

Henley told IDEAS about life growing up with a facial difference.

"As a kid in elementary school, someone would insult me, but I had to not be sensitive... Yes, people were mean. And yes, I got stared at. Yes, they insulted me. They made fun of me. And I was humiliated constantly. But there was this underlying message that I deserved it because I was different."

'Fix me'

Henley and her twin sister Zan were born with a rare condition called Crouzon syndrome, a craniofacial disorder where the bones in the skull fuse to each other prematurely.

Throughout her childhood, the twins underwent multiple surgeries during which doctors physically expanded their skulls, shifting their facial features out of place. Without the surgeries, the sisters risked brain damage and death.

"My eyes were too far apart and too crooked. My nose too big. My jaw was too far back, my ears too low. Some of it was for medical purposes, other times for esthetics we would sit in a room with while doctors took pictures of our faces from every angle," she writes.

"They would pinch and poke, circling our flaws.We would sit there and let them know. We would sit and let them pick apart our every imperfection. And we wanted it. We did.

"'Fix me,' I would beg."

Ugliness as evil in pop culture

On top of the prodding of doctors, the taunts of classmates and the biting words of journalists who wrote about her and her sister's condition, Henley found that in the movies, books, and shows she consumed, she couldn't escape a cultural narrative that difference is ugly, and ugliness is evil.

"We have this narrative that to be pretty is to be good, to be ugly is to be evil," she told IDEAS.

Henley cites the example of the 2017 blockbuster film Wonder Woman, where one of the villains, Dr. Poison, has an unexplained facial prosthetic. At the climax of the movie, her prosthetic is removed, showing her disfigured face.

"You're supposed to see her for all that she is: evil. It's a physical representation of her lack of humanity," said Henley.

Henley said the trope of characters with facial differences or disfigurements is so normalized — from Darth Vader, to Freddy Kreuger, to James Bond villains — that audiences often fail to recognize how ingrained the practice is and how it can impact the lives of those living with conditions that make them look different.

"It's easy to look at stories like Wonder Woman and be like 'it's just a movie,' but it isn't just a movie. We see these representations on screen and it does impact real people. There are people who are afraid of people who look different just because that's all that they know," she said.

Henley isn't alone in calling out the practice, which is common even in children's entertainment.

A British charity called I Am Not Your Villain is currently working to end the practice of using facial scars, burns, and marks as "a shorthand for villainy." And in 2018 the British Film Institute vowed not to fund movies with disfigured villains.

Henley, who has written about her life and her condition in a number of mainstream outlets, writes that she overcame much of what she was subjected to by reclaiming her own narrative. Even the title of her book is inspired by a journalist who described her little girl face, in a profile of her and her sister, as one fit "for Picasso."

"If I listened to those voices telling me I wasn't wanted, I wasn't good at anything, I was ugly, I was too hideous to be seen, I would never be able to live my life. And so part of my coping strategy, I guess, was anger," she said.

"[I was] pushing back against everything that people said that was negative about me — and I got angry for myself that I was being subjected to that and that people were trying to tell me that everything about me was wrong just for existing."

Henley appears in an episode of IDEAS as part of a series about the body, called Body Language.

Other guests in the episode:

Jess Zimmerman is the author of the book Women and Other Monsters.

Naomi Baker is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Manchester and the author of Plain Ugly: The Unattractive Body in Early Modern Europe.

George Grinnell is an associate professor of English and English Cultural Studies at the University of British Columbia Okanagan campus.

*This episode was produced by Matthew Lazin-Ryder.

This episode is part of our series called Body Language — exploring what our bodies express and repress, both literally and symbolically. Find more Body Language episodes here.