Buddhism and science: a doomed romance?

Validating a religion as scientific is misguided, says Evan Thompson

*Originally published on October 2, 2020.

When Evan Thompson was just eight, he read a biography of the Buddha. He grew up around renowned Buddhist teachers. At university, he studied Buddhist scripture, philosophy and classical Chinese. And his mentor in graduate school was Francisco Varela, a neuroscientist who was also a serious practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism.

But Thompson is not a Buddhist.

That fact surprises a lot of people he meets. So he called his latest book: Why I Am Not a Buddhist.

However, the book is not as autobiographical as its cover may suggest. Thompson takes a critical look at the relationship between religion and science through the lens of what he calls "Buddhist modernism" and advocates instead for a fruitful dialogue between the two.

'The truly scientific religion'

Buddhist modernism refers to a form of Buddhism that came to the West in the 19th century. When colonial powers in Asian countries like Burma (Myanmar) or Sri Lanka sought to promote Christianity, they argued for its intellectual and spiritual preeminence. But as Thompson says, Buddhist monastics and intellectuals countered with a brilliant defence of their own religion.

"They turn the tables… and they say, well, Buddhism is actually the scientific religion because we don't believe in a creator God. We don't believe in an immortal, unchanging, essential soul," Thompson tells IDEAS.

"We ground our ethical system on an understanding of cause and effect. We emphasize causality, that things are impermanent, that things are in flux. So they present Buddhism as either not a religion, or as the truly scientific religion."

As it turned out, Buddhist modernism was tailor-made for the modern West's preoccupation with rationality, scientific validity, and independent thought. But as Thompson argues, things have gotten a little out of hand.

Buddhism now enjoys a kind of exceptionalism among religions. It's regarded as a 'science of the mind,' mindfulness meditation is a 'brain-changing,' commodified, individualistic activity, and complex ideas of the self in Buddhist teaching are conflated with scientific contentions that the self doesn't exist because it can't be found in the brain. It's at this point, Thompson argues, that we begin to miss the point.

"One of the problems with this scientific statement that, 'Well, science shows that there is no self and that validates Buddhism,' is it just completely elides or ignores the difference between a scientific description and scientific use of a concept like the self, and the Buddhist one, where the Buddhist one is inherently ethical or normative," says Thompson, a philosophy professor at the University of British Columbia.

"The idea that you would validate or ground a religion on the basis of whether the content of its statements was more or less scientifically certifiable, seems to me as misguided as thinking that in the case of art, you're going to judge something to be of more worth artistically, depending on whether it's more compatible with or comprehensible in terms of science."

A cosmopolitan framework

Central to Thompson's argument that we should acknowledge the different functions of science and religion is that we should have a more robust understanding of religions themselves. Again, he draws on the example of Buddhism.

Buddhism was born in a fertile landscape of spirituality and philosophy. In its earliest phases of growth in India, it was just one of many ways of making sense of existence.

And over the course of its history, Buddhism has been part of cosmopolitan cultures, in conversation with many other traditions: Hinduism and Jainism in South Asia, Confucianism and Daoism in China, and in more recent times, in the pluralistic cultures of North America and Europe.

It's the richness of this cosmopolitanism that Thompson wants to draw attention to.

"The idea is that we should identify as human beings with the larger human community, rather than with exclusively local and particular identities ... The cosmopolitan framework, I think, is important for understanding religion in relation to science and art. It provides a kind of overarching framework for seeing human life as consisting in many different forms of meaning-making," says Thompson, adding "what holds them together in a larger sense is the shared humanity of them — the larger human community."

After he finished writing Why I Am Not a Buddhist, Thompson realized a shortcoming of the cosmopolitan tradition: that it's anthropocentric — human-centred. And in a time of climate crisis, that shortcoming is important to acknowledge and integrate into our experience of the world.

"I see cosmopolitanism as kind of an evolving philosophical framework. It's not a fixed thing. And I think one of the challenges for it here and now is to evolve its sensibility beyond a kind of human exceptionalism that really attunes us, sensitizes us to the larger value and good of the biosphere, which I think is absolutely crucial for us to find our way through the climate crisis."

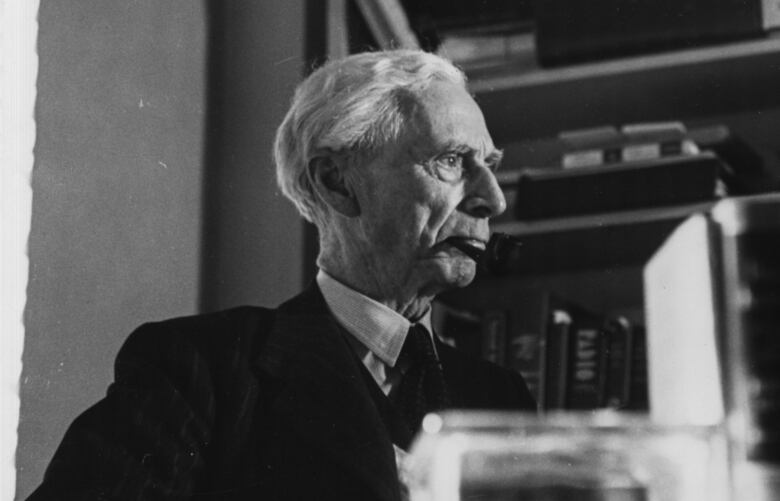

The title of Thompson's book is reminiscent of a famous essay by mathematician and philosopher — and prominent atheist — Bertrand Russell, called Why I Am Not a Christian. But where Russell's essay was an attack on Christianity, Thompson regards his own critique of Buddhism as a friendly one, given his lifelong relationship with it.

"What I take from Russell," Thompson says, "is the idea that we should try to look at things as clearly as possible with a critical eye, and that it's important to do that in a way without fear and without compromising our intellectual standards or our philosophical standards."

* This episode was produced by Sean Foley.