An Unequal World: Are universal human rights actually possible?

History shows us the search for a documented list of people's rights goes back millennia

In 1948, Canada was behind the big push at the United Nations to develop a Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

It was a heady time. The world had just emerged from the Second World War. And with the creation of the United Nations, there was widespread hope that creating an international human rights framework would protect people against future abuses.

More than 70 years later, there remains much more that needs to be done. The world is still a wildly unequal and violent place where human rights abuses are ubiquitous. However, we can look back at the UN Declaration and see some of the basic missteps that occurred right at the very start.

"We tend to think of human rights as something that we put on a pedestal above the fray of our normal politics" says lawyer and human rights activist, Azeezah Kanji.

"But looking back to the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights at that time, and even with the way now that human rights are invoked, we see that they are deeply enmeshed in politics, and in the relationships of power that are prevailing at the time."

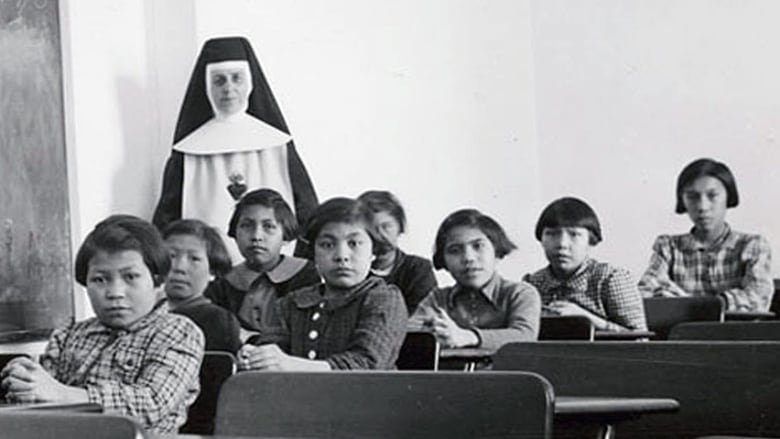

Kanji adds that the document was drafted when much of the world was still colonized.

"And the drafters of that declaration and the propagators of it were some of the very same states that had been involved in brutally colonizing, raping, genocidal, massacring large portions of the world."

The idea that there might be such a universally agreed-on list of human rights goes back thousands of years, we've been trying to agree on this thing forever, so maybe it's not a hopeless cause, just an ever- receding goal.

Which brings historian historian Arne Kislenko to ask: "Is there a universal agreement, or can there be one?"

"The historian in me would say, listen, whether we like it or not, there are abundant differences between peoples and nations which still exist, regardless of how they came about ...that is absolutely a good place to start for what's gone wrong with the world."

Azeezah Kanji's point — that it was largely the most powerful nations that framed the original UN Declaration— suggests the ongoing necessity to look to other voices, other cultures in the framing of how we move forward in human rights issues.

It's understanding these cultures that allow for the flourishing of human rights in the modern age, adds Akila Radhakrishnan. The activist argues the way forward is to interpret human rights progressively by centering the real needs of people, rather than getting tied up in legalisms.

"We set something out there that's aspirational, but it doesn't make it perfect," Radhakrishnan tells IDEAS. She explains that a common issue in the discourse around human rights is the focus is often on protecting the law and "not about protecting the people."

"If something is written in a way that is too much in the colonial tradition, we need to rethink it.

"We should be listening to those voices and thinking about how to adapt (the law) and put it into practice in a way that responds to real needs."

Guests in this episode:

Arne Kislenko is a historian who teaches at Ryerson University and the University of Toronto.

Azeezah Kanji is a legal scholar and director of programming at the Islamic Noor Cultural Centre in Toronto.

Akila Radhakrishnan is a human rights activist and director of the New York based Global Justice Centre.

* This episode was produced by Philip Coulter.