5 top researchers granted the 2019 Killam Prize — considered 'Canada's Nobel' award

The 5 Canadian scholars received $100,000 for reaching new heights in their field

*Originally published on September 6, 2019.

A Killam Prize is about as prestigious as it gets for scholars in this country — often referred to by the Canada Council as "Canada's Nobel."

Five scholars win a Killam Prize each year, a $100,000 award for Canada's most outstanding research. There's one winner in each category of scholarship: humanities, social sciences, natural science, health science, and engineering.

Killam Prize winners this year shared their stories with IDEAS host, Nahlah Ayed.

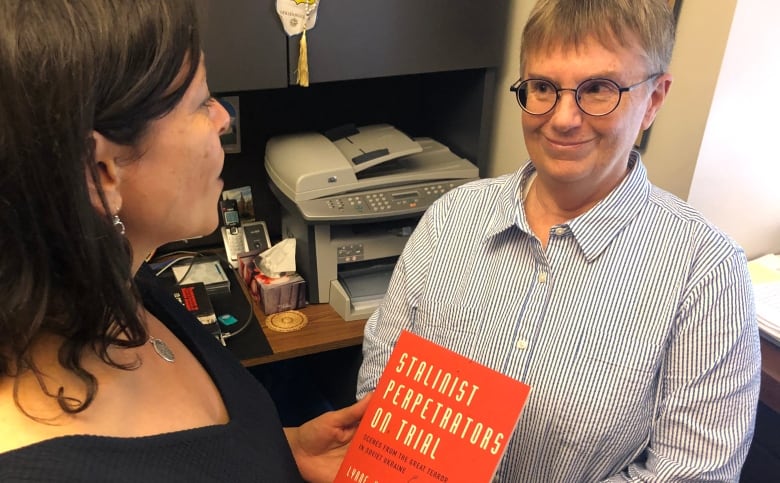

Lynne Viola

Field of Study: Humanities

Lynne Viola considers herself a 'documentary fetishist'. She's spent a lifetime digging through the archives of Soviet Russia. She wants the true story of Joseph Stalin's regime, a government famed for its deceit and secrecy.

"The documents I read are always full of lies," said Viola, a history professor at the University of Toronto.

"You have to work hard to find the truth. It's a real warning of how quickly lies can become 'the truth'."

Viola's decades-long investigation into Soviet government documents has made her the world's leading archival researcher of Stalinism.

As extreme as Joseph Stalin was, Viola sees important similarities between his misrule and some of today's deceptive government leaders.

"I worry very much about what's going on in the UK and the US," said Viola, while pointing out that countries like Turkey, Russia, Poland, and the Czech Republic are in more dire straits.

Yoshua Bengio

Field of Study: Natural Sciences

University of Montreal professor Yoshua Bengio is a pioneer of 'deep learning' —a crucial field for developing artificial intelligence.

"It's both scary and exhilarating," said Bengio, describing the discoveries at Mila, the Quebec artificial intelligence institute he founded in Montreal.

"Who are 'we' when we're building machines that could eventually be as smart as us?" Bengio asked.

"The progress that's being made is so huge that it forces us to ask questions about what it means to be human, what we want to do with that technology... what is acceptable to do, and what is not acceptable."

Keith Hipel

Field of Study: Engineering

It initially sounds strange — an engineer who specializes in solving people's disagreements. But University of Waterloo professor Keith Hipel argues a 'systems design engineering' approach is the most promising way to resolve conflicts between differing interests and value systems.

"I was always very interested in nature and the environment," Hipel said.

"Civil engineers have to deal with the public all the time. I realized we need more formal methodologies to deal with information."

Hipel's approach is to model how physical systems and social systems interact. By drawing up a good model for what's going on between people who disagree, mapping out the "decision-makers" and their various options, an engineer can work out a possible route to the solution, even potentially to the impasse regarding carbon emissions policy.

"I would say that's real engineering today, and a good philosophy for the future if you want to solve these problems," said Hipel.

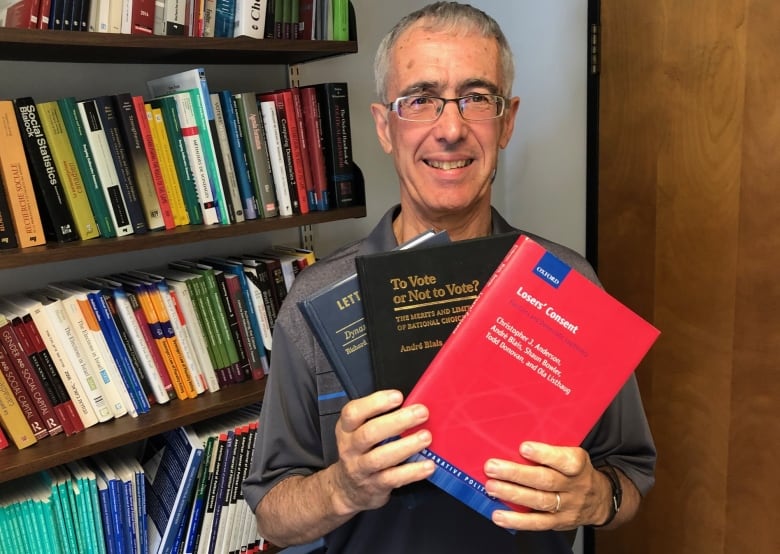

André Blais

Field of Study: Social Sciences

It's good news for democracy if politicians accept the results of elections even when they lose. But why do they?

It's good news, too, if people vote in elections. But again, why do they?

"You know your vote is very unlikely to change the outcome of the election," said André Blais, professor of political science at the University of Montreal.

"A lot depends on whether people think they have a moral duty to vote."

Blais' research helps explain how people think about voting and elections. He also explores the pros and cons of various methods of proportional representation.

"I would like voters to be able to express their preferences in a subtle and nuanced fashion," Blais said.

However, his main drive as a scholar is toward his own greater understanding, rather than toward any particular cause or change.

"I'd like to think that what we learn might be useful," he said, "but I must admit that the first motivation is simple pure curiosity."

Stephen Scherer

Field of Study: Health Sciences

High up in a glassy tower in downtown Toronto, you'll find many of the world's top gene researchers hard at work. For 20 years, the Centre for Applied Genomics has been at the cutting edge of discovering the secrets of life and evolution.

It's also where you'll find Stephen Scherer, the centre's co-founder.

"It is amazing how fast the technology has allowed us to read the sequences and edit our genomes," said Scherer.

The lab can read thousands of gene sequences each year. Soon, perhaps within five or 10 years, Scherer predicts, they will be able to process millions per year.

"[Then] we can use approaches of artificial intelligence to decode the decision-making tree of human evolution. That's where all of this is going," Scherer explained.

"It will move our understanding of ourselves, of our species, to a level we could not have imagined before. How we use that information is the critical thing."

Guests in this episode:

- Lynne Viola is a professor of history at the University of Toronto. Her books include Stalinist Perpetrators on Trial: Scenes for the Great Terror in Soviet Ukraine.

- Yoshua Bengio is the founder and scientific director of Mila, a Montreal institute for research into artificial intelligence and 'deep learning'. He's also a professor of computer science and operations research at Université de Montréal.

- Keith Hipel is a professor in the department of systems design engineering at the University of Waterloo. He is also co-ordinator of the university's Conflict Analysis Group.

- André Blais is a professor of political science at Université de Montréal. His books include To Vote Or Not to Vote? The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice Theory.

- Stephen Scherer is co-founder of the Centre for Applied Genomics at Toronto's Hospital for Sick Children. He's a professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, and director of McLaughlin Centre.