'What's on the Hit Parade?' Rare letters show Japanese-Canadian internment through teens' eyes

A trove of newly donated letters shows the pain of isolation for interned teens

By Matt Meuse

Sept. 24, 1943

Dearest Joan,

Just a sheet with few lines to say "hello" and "how are you?" Its been quite a long time since I've heard from you last, and I hope you are all well as we are also. I imagine you're going to school every day and enjoying your everyday life. That's swell! Life is very dull out here... no school, no play.

Think of us in the field pulling and topping beets while you are doing your geometry, social studies, etc., will you, Joan? And I'll think of you having a wonderful time while I work.

— Sumi Mototsune, Raymond, Alta.

It's not every day that cleaning out one's attic unearths a 70-year-old trove of letters unlike any currently known to historians — but that's exactly what happened to Joan Gillis.

In the midst of a cleaning spree, Gillis came across a box in which she had kept a collection of letters from friends sent to her during the Second World War — friends who were Japanese-Canadian, and had been sent away from their homes on the south B.C. coast to work camps and farms in the Interior, the Prairies and beyond.

"I don't know why I kept them in the first place," says Gillis, now 90 years old. "I just had a sense that maybe they were worth holding on to."

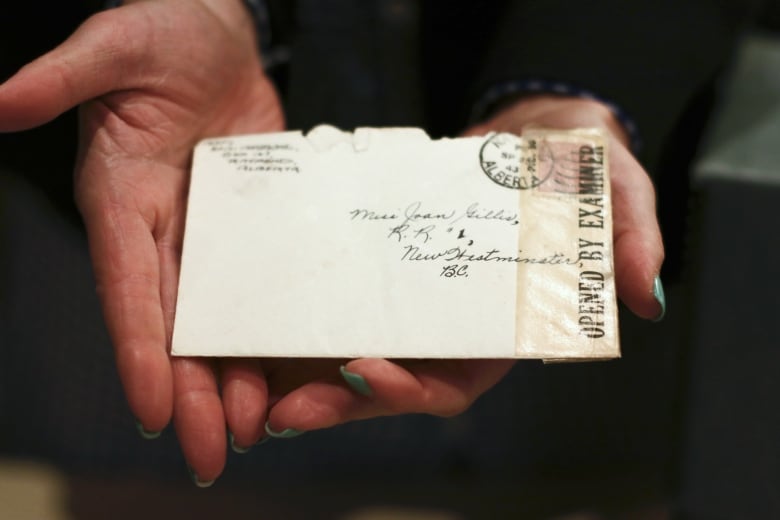

The collection consists of 147 letters from a dozen different correspondents, including pictures, postcards and envelopes — complete with stamps indicating their examination by government censors.

April 28, 1942

When we got to Raymond I nearly died, but when they skipped us to five miles past Magrath again I really died twice. And if I don't hear from all my friends; that means a certain Anne, Joan, Betty, Margaret, and many others; I'll die a third time and never wake up again.

— Yoshio Nakamura, Magrath, Alta.

The earliest letters date back to the spring of 1942, when an estimated 22,000 Japanese Canadians were forcibly removed from the B.C. coast by government order. Some were sent to work camps in the Interior; others were sent to work on farms in the Prairies.

Gillis was only 13 years old at the time. Most of her correspondents were that age or several years older, all of them Japanese-Canadian. They ranged from close friends to passing acquaintances, most of them pupils at Queen Elizabeth Secondary School in Surrey, B.C.

In their letters, Gillis's friends talk about the loneliness and homesickness of being sent away and the harsh conditions and manual labour they were subjected to.

"I think probably the first thing that struck me was you couldn't tell that these people were different ethnicities," says Gillis's cousin Steve Turnbull, to whom she reached out after rediscovering the letters.

"They were friends. That was it."

August 3, 1942

Dear Joan,

Many thanks for your most welcome letter. I received it with greatest pleasure on the 24th. Every letter we're getting now is censored and just to send a letter 30 miles it takes over a week, because every letter we write goes back to B.C. to be censored.

— Tadashi Nagamori, Headingley, Man.

Tadashi Nagamori is one of the few surviving people whose letters found their way to Gillis. Now 94, he lives in Winnipeg, where his family was sent in 1942.

"I was a young kid then," Nagamori says. "You can't help it. The war was on and that's the way with war."

Gillis and Nagamori didn't know each other while living in Surrey, but were introduced by a mutual friend, Yoshiyuki Okamura, who had also been sent to the Winnipeg area. They got to know each other by mail, exchanging photos, drawings and stories.

Stefan Jonasson, high school sweetheart and now husband of Nagamori's daughter Cindy, is grateful to Gillis for preserving his father-in-law's letters for all these years.

"I sit back and think, here was a 13-year-old girl who obviously grasped what was going on and had the presence of mind to maintain relationships with people who were being demonized and victimized," Jonasson says.

"She saved letters that just talked about what it was like to be an everyday Japanese-Canadian teenager, wanting to have friends, wanting to listen to music, wanting to go to dances, wanting to just enjoy childhood."

"It's almost magical."

June 8, 1942

Dearest Joan,

Thanks a million for your letter. I received it on Saturday. Gee, I was disappointed when you said that the Blues won, but oh well, a person can't do anything now I suppose but to laugh it by.

Did the Q.E. school put out a paper or an annual of some sort? If they have, if you happen to have a extra copy, I wonder if you could send me one.

What's on the Hit Parade this week? I guess I wouldn't know the song, but anyway, I like to know.

— Setsuko Fujii, Kaslo, B.C.

Turnbull, who was working as the curator of the Japanese Canadian National Museum in Burnaby when Gillis first contacted him about the letters, immediately recognized their historical importance. He set to work cataloguing them and researching various institutions that might be interested in them.

Now, 15 years later, the letters have a new home at the University of British Columbia's Rare Books and Special Collections library. Laura Ishiguro, an assistant professor in UBC's history department, says the letters provide a unique perspective of the internment and exile of Japanese Canadians.

"[These teenagers] miss their friends," Ishiguro says. "They've been torn from their home and they talk about that. But, you know, they're also bored. And they care about the songs on the Hit Parade. And they care about stuff that gives us a totally different vision, and reminds us that these are teenagers who certainly weren't plotting the downfall of this country."

Ishiguro, who specializes on the history of the British Empire and on letter-writing in particular, says she doesn't know of a similar collection in existence anywhere else.

April 25, 1942

To talk about the trip, we left New Westminster on Monday at 9:25 a.m. and reached Raymond at 10:30 a.m. There were many people going. The trip was wonderful, but the only disadvantage was that I could not sleep for the whole two nights on the train. (Hardly nobody did.)

I cannot hardly believe I'm in Alberta. As soon as this trouble is settled, I'll come home right away.

— Sumi Mototsune, Raymond, Alta.

Henry Yu, an associate professor in UBC's history department, characterizes the removal of Japanese Canadians from B.C. as nothing short of ethnic cleansing.

"I would use that term, even though it wasn't a term that was used back then," Yu says.

"There were euphemisms, nice words like evacuation or internment, as if it was for their own good, [but] really this was a removal, an exile and a deliberate attempt to ethnically cleanse British Columbia of Japanese."

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December of 1941, Yu says, provided an excuse for anti-Asian agitators to expel B.C.'s Japanese-Canadian population — something they'd been wanting to do for years.

Their property was seized by the government, ostensibly to be held in trust until they were allowed to return home. But when the order was finally lifted in 1949 — four years after the end of the war — many found their property and belongings had been sold off in their absence, often for pennies on the dollar to neighbouring (white) farmers and fishermen. There was nothing to return home to.

"Basically it was like, we're going to take you, exile you, and then we're going to sell your stuff to pay for the process of removing you," Yu says.

"That's really the darkest chapter," Yu continues. "Even though there was an apology and redress [from the government] in 1988, you could say that personal loss of property and others gaining from it — that's really never, I think, properly been reckoned with."

Oct. 14, 1942

We have just started on our beet harvest about a week ago. Boy, I found this job really miserable. Specially when you're shaking the dirt off. The only thing the owner does at harvest is come along with a tractor and loosen the beet out of the heavy gumbo soil. Then we go up two rows a piece throwing eight rows of beets into one row, shaking the dirt off at the same time. Soon as we make a pile of beets, we throw the leaves over it in case it freezes before they come to collect.

— Tadashi Nagamori, Headingley, Man.

Though Nagamori tends to play this all off as bygones not worth worrying about, the sense of loss is evident when he reminisces about his B.C. home.

"Where you're brought up, where your home is, where your own life is — that's taken away from you. What is your life then after that?" he says. "You have no life."

"They take the place where you were born and you played, tramped the ground and dirtied the house," he continues. "What are you going to do? You'd like to go back to that. No matter how dirty it is, you'd like go back. But was it sold. It wasn't fair, but what are you gonna do, eh?"

Like many exiled Japanese Canadians, Nagamori never returned home to B.C., even after the order was lifted.

Sept. 24, 1943

Ah! But I have so many things to tell you about the beets and everything out here; I don't think I could write everything I want to in the letter. I am just wishing for the day when you and me [meet again], telling and hearing each others' story for hours and hours of what we've missed. I only wish it would be soon, don't you think so, Joan? I'll write again; a longer letter, and I'll be waiting for yours every day.

Your friend as ever,

Sumi Mototsune, Raymond, Alta.

For Ishiguro, Gillis's letters are a beacon of light in an otherwise exceedingly dark chapter of Canadian history.

"Many of the stories that we tell about Japanese Canadians in the Second World War focus exclusively on them, on their pain and trauma and feelings of betrayal, and other explanations focus on non-Japanese-Canadian people's fears or hatred," she says.

"What's so incredible about these letters is they remind us that those weren't the only ideas in the 1940s. We have an example here of friendship ... between Japanese- and non-Japanese-Canadian people that reminds us that it's never as simple as, those were just the ideas of the times."

Though it's been more than 60 years since Gillis and Nagamori exchanged letters, they now have each others' mailing addresses once again, and Nagamori has promised to send her a hand-carved wooden turtle.

For his part, Turnbull is happy the letters have finally found a home at UBC, where they will be digitized and made available to anyone who wants to read them.

"Letters and other artifacts — they're material things. But we tend to forget that they're manifestations of people, and there are people behind these letters," Turnbull says.

"Even though the letters may be considered these old artifacts now safely ensconced at UBC ... the fact is that there are living human beings behind them with real flesh-and-blood stories."

"They haven't gone away; they're still there."

Listen to the documentary "Dearest Joan" by clicking the Listen link at the top of this page. Or download and subscribe to our podcast so you never miss a show.

Letters in the documentary were read by Ellie Petrovich, Daniel Petrovich, Charlotte Taylor and David Gauthier.

About the producer

This documentary was co-produced and edited by The Doc Project's Alison Cook.