Some Canadians say remote employee tracking is justified. Others are dead set against it

Company removes worker after remote tracking software helped determine they were sleeping on the job

The electronic employee surveillance system installed at Lori McEniry's company helped determine that an employee was sleeping on the job, while working from home. That person ended up being let go.

McEniry is the principal owner of Faxinating Solutions Inc. in Quebec, which employs roughly 40 people, and services the supply chain by processing invoices and purchase orders.

She says the tracking began once employees were forced to work from home in March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

"We monitor reports and we look for periods of time when they [employees] are not busy," said McEniry. "We also check those times against whether or not there were enough transactions in the queue to process, or whether they were in a meeting."

According to a 2021 report from Toronto Metropolitan University's Cybersecure Policy Exchange, employee surveillance has become more prevalent during the pandemic.

Detractors say tracking remote workers is worrisome, citing personal security and privacy issues, regarding tactics such as keyboard monitoring, webcam surveillance, and facial recognition programs.

McEniry's company uses software that automatically generates reports at the end of each day, illustrating how many transactions each employee processes, and when.

"We have certain service level agreements with our clients that have to be processed within a certain time, so the employees have to be productive."

Everything the employees do is measured and processed, McEniry says, including when they take scheduled breaks — but that they're also upfront about their expectations, such as how long breaks should be.

"We establish, I'd say, a minimum period of time [of inaction] that would be flagged. And it's not five minutes. It's a little bit longer than that. But it's more like anything over a standard coffee break."

As of this month, Ontario companies with more than 25 staff are obligated to disclose if and how they monitor workers, making it Canada's only province with legislation on employee monitoring. Alberta, British Columbia and Quebec require employers to disclose data collection under privacy laws.

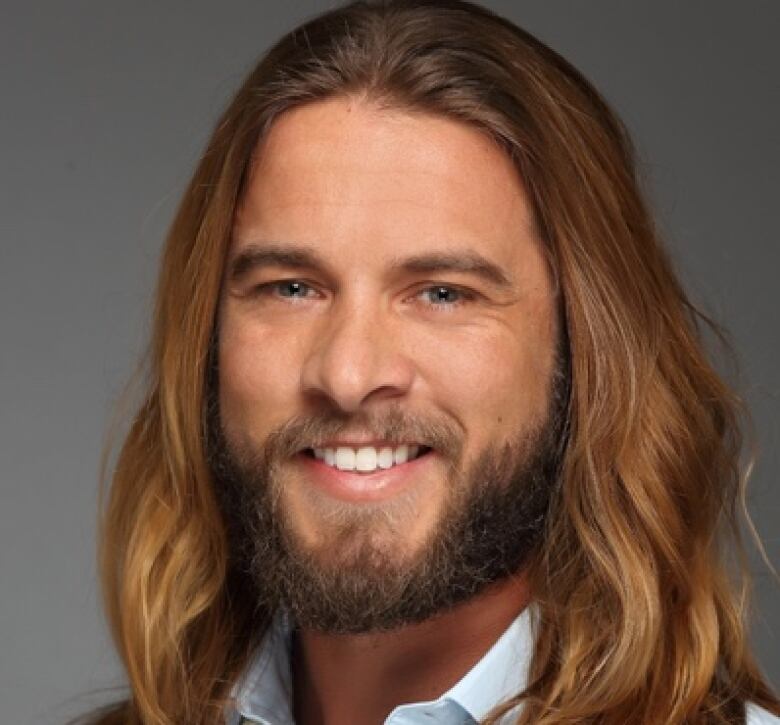

Toronto employment lawyer Rich Appiah says the new legislation doesn't clearly articulate what employers can or can't do. That puts the responsibility on employers to try to identify what they want to do in the workplace, and then communicate it to employees.

It doesn't specify how or whether employees can file a complaint about the monitoring either, he added.

"Nothing in the legislation says that employers can't monitor and there's no restrictions on the monitoring at all," Appiah said. "There's no kind of standard as to what's appropriate and what's not appropriate."

As for provinces like British Columbia, Quebec and Alberta, Appiah says private and public sector workers do have the right to bring complaints to privacy commissioners. But he also said there's not much they can do if their companies direct them to install software on work devices.

"As our workplaces change, as businesses become more creative and the services that they offer, we need to give them some flexibility in their ability to monitor their employees," he said.

Jean-Nicolas Reyt thinks employee tracking is "shortsighted" and runs the risk of creating unhealthy and unsuccessful relationships in the workplace.

"The problem is that these metrics are usually very poor proxies for performance," said Reyt, an associate professor of management at McGill University. "Whether or not people are spending a lot of time at the office or behind a keyboard is actually pretty irrelevant."

Reyt says an employee's relationship with their boss and employer can be a "full psychological contract" that goes beyond the legal agreement between them.

"It includes things like, 'Do you have my back?' or, 'Do I feel like I'm in a place where I'm respected?' or 'Am I treated right?' If these factors are not there, they're seriously challenged when employers are spying on employees."

Toronto's Ali Qadeer says he's opposed to remote employee surveillance, particularly as more people are working from home than ever before.

"Nowadays, in this remote period, computers reflect so much more of people's lives than their work life," said Qadeer, an associate professor of graphic design at OCAD University.

He thinks digital tracking goes so far as posing a threat to workers' rights.

"If you're part of a movement; if there are issues in the workplace; if you're trying to organize a union, those ideas can sort of spread through, and in conversations with people on smoke breaks and [at the] water cooler. But when you're suddenly in a remote setting, suddenly everything is logged."

Vass Bednar, public policy entrepreneur and adjunct professor at McMaster University, says that when companies track their employees, they risk treating them more like robots than people.

She says workers should be told how and who is gathering their data, and if there are consequences, including termination, to what's found in the data being collected.

"I think it just replicates managerial mistrust. In what used to be the traditional workplace of hot desks, open concept, en vogue offices, you can glance over and see what a colleague is working on," she said.

"Does that mean you should? Does that mean a record should be created or data should be stored?"

With files from Jason Vermes and Nisha Patel.