Researcher angry alcohol industry lobbied Yukon to 'squash' cancer warning study

A Globe and Mail Access to Information request revealed industry efforts to shut research down

The alcohol industry in Yukon didn't like a government-funded study that put cancer warnings on alcohol bottles. And so, according to emails obtained by the Globe and Mail via an access to information request, they lobbied the Yukon government to shut it down.

In December — just a few weeks into the study — the Yukon Liquor Corp. suspended the investigation by researchers from Public Health Ontario and the University of Victoria's Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research.

The study resumed in March, but references to the cancer risks associated with drinking are no longer on the labels.

The Yukon Liquor Corp. says it believes Health Canada should take the lead and tackle this issue.

"When the study began and national producers began to express their concern, especially with regards to the cancer label, it never caused us to question the science behind the labels," Yukon Liquor Corp. manager Patch Groenewegen, told As It Happens in an emailed statement.

"The liquor industry indicated a possibility and/or likelihood of legal action. The challenge to us as a small jurisdiction was to decide whether to spend money on social responsibility messaging through a range of tools, or to risk spending significant money on protracted legal costs … we chose to direct resources toward social responsibility initiatives."

- Liquor industry calls halt to cancer warning labels on Yukon booze

- Yukon alcohol producers say they were left in the dark about warning label study

Tim Stockwell is the co-principal investigator on the study and the director of the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research. He spoke with As It Happens host Carol Off about why he's not surprised by these revelations.

Here is part of that conversation.

Professor Stockwell, what do you make of these emails that reveal how the alcohol industry lobbied the Yukon government?

There's nothing in them that surprises me because I was in touch with the Yukon government ... to try to salvage our little study.

So we knew this was going on, but it's a relief to see it finally, you know, in the glare of full daylight so everyone can see what was actually going on.

And it's in the glare of full daylight because the Globe and Mail did an access to information request and got these emails.

In the emails they describe your labels, your study, as "false" and "alarmist." What did the labels actually say?

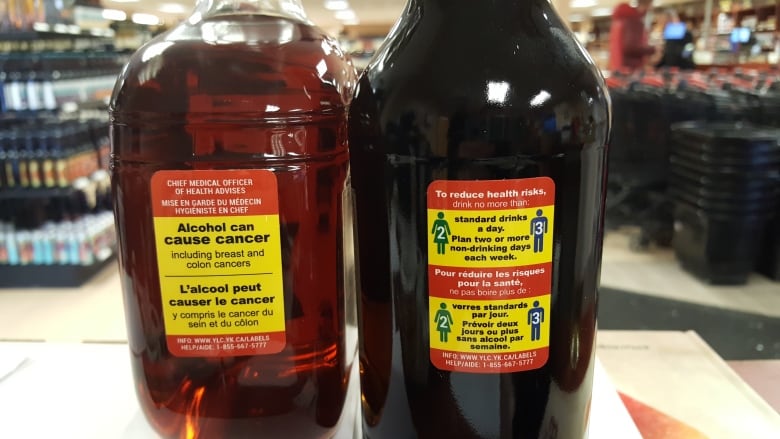

They said three simple things. One is that alcohol can cause cancer, and we listed three specific varieties.

We described Canada's low-risk drinking guidelines with little images and numbers of standard drinks to have in a day.

And then, we haven't yet done this, our third label which is still coming is helping consumers know how many standard drinks there are in their bottle of beer, or bottle of wine or spirits.

When you were told that you you couldn't continue with this ... what were you told were the reasons for that?

We knew it was private and confidential information provided by the Yukon government that they were worried about litigation.

And we'd been reassured all along that they completely understood the science and the minister responsible for liquor and gaming there in the Yukon, John Streicker, said this publicly in a press conference.

The only reason that they discontinued the cancer warning labels was because they didn't have the resources to fight the alcohol industry in court.

The letters [are] from Beer Canada, Spirits Canada and the Canadian Vintners Association. Those were the three groups that were lobbying the Yukon Liquor Corporation.

Beer Canada said that your claim on the label, that alcohol can cause cancer, is a misleading statement. What do you say to that?

It's utterly false. The really almost laughable thing about these emails is that they're purporting to be ... experts on the health consequences of drinking alcohol.

[The American Society of Clinical Oncology] put out a statement in The Lancet recently celebrating 30 years and saying, "Why has there been no action? Why is it hardly anybody knows alcohol causes cancer?"

This is the reason. Because when you try and put the message out there, it's squashed.

This is a very small study that you has going in Yukon, So why do you think they reacted so strongly to such a small sample study?

Obviously it's bad for the sales of their product. So even though it's small they just wanted to squash it. To stifle it at birth basically was their strategy.

But I think it backfired because of all the publicity that it generated.

And was there a plan to see this study done elsewhere?

Well we were just delighted that we were invited by the Yukon to do this study.

I've been put in print that, I don't know, that at the present time there's no evidence that warning labels change behaviour. And if any study could have done this, this little study in the Yukon could have shown that in principle there was was a change in behaviour. We don't know that.

If we'd have been able to complete the study, we'd have found out.

Written by Sarah Jackson. Interview produced by Chloe Shantz-Hilkes. Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.