British suffragette was the 1st to go to jail. Now, a letter to her sister has been found in B.C.

Annie Kenney wrote to her sister Nell upon being released from Strangeways prison in Manchester

The letter begins, "My Dear Nellie, You may be surprised when I tell you I was released from Strangeways yesterday morning."

It was written in 1905. The author was Annie Kenney, a working-class woman from Manchester — who was the first suffragette to be jailed for fighting for women's right to vote.

The letter is the first-known testimony from a suffragette about her experience in prison — and it was found in the Royal BC Museum's archives.

Lyndsey Jenkins, the University of Oxford historian who made the discovery, spoke to As It Happens host Carol Off. Here is part of their conversation.

What did Annie Kenney do to get thrown in Strangeways prison?

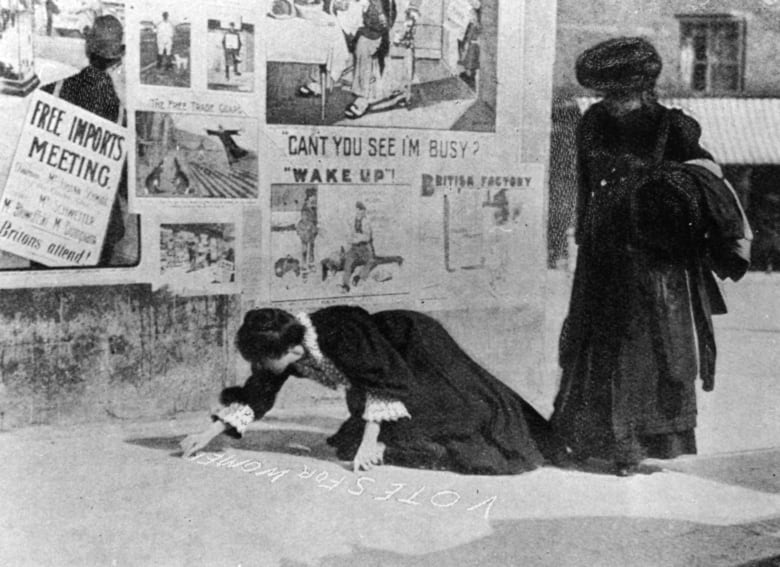

This was the first moment that women had gone to prison for the vote. And this was a very deliberate choice by them. Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst went to a Liberal Party meeting during an election campaign and they stood up in the meeting and demanded, "Will the Liberal government give votes to women?"

They get booed. They keep asking. And eventually, they get thrown out of the hall. There's a scuffle. Christabel Pankhurst spits at a policeman. And that's committing assault, that's enough to get them arrested.

And they're given a choice of paying a fine or going to prison. And they choose prison, because they know that's the thing that will have most impact.

Christabel Pankhurst was the daughter of Emmeline Pankhurst, the founder of the suffragette movement in England, is that right?

That's right. There are three daughters in the Pankhurst family — all of whom are very involved in the suffragettes in different ways.

Christabel leads the WSPU [Women's Social and Political Union]; Sylvia is more radical, more "lefty," works among working-class women in the east end of London; and then there's Adela, often the forgotten daughter, who ends up going to Australia.

And there's a lot of falling-out among the Pankhursts. They didn't have a very harmonious family relationship.

How did Annie Kenney get involved with the Pankhursts? What led her to join up with Christabel?

The Kenney family were always very interested in politics — but in a particular kind of socialism. They weren't very interested in labour activism or trade unions or factory organizations.

They almost saw politics as more of a moral and spiritual cause then worrying about the day-to-day business. They were always on the lookout for people who inspired them. Christabel Pankhurst was very much that sort of person: extremely charismatic, very dynamic.

And Annie and her sisters heard Christabel Pankhurst early in 1905, talking about the importance of votes for women. And they were just so moved and struck by the force and fervour of her commitment.

And at that moment they sort of decided, "Yes, this is what we've been looking for."

But it's one thing to get involved politically, another thing to get yourself thrown into prison. What was the reaction of [her] family?

That's something the letter really gives us a good insight into. One of the things that Annie says in the letter is how grateful she is for all the support that the family has shown. She's just concerned about this one sister, Alice, who she's concerned is going to be particularly angry about the whole thing.

And that's because Annie Kenney really was risking quite a lot — not just her own job, her financial security, but also her family reputation.

It was a really big decision to go to prison. This is the first time women are doing it — it's not something women would have done before.

That kind of cycle that Annie Kenney went through in 1913 — hunger strike, force-feeding, release, go on the run, re-arrested — it's incredibly draining and has a massive impact on her health and well-being for the rest of her life.- Oxford University historian Lyndsey Jenkins

In this letter, what does Annie Kenney say about what it was like to be in prison?

She doesn't really say much about prison at all. She, I think, finds it quite difficult to articulate how difficult it is to be in prison.

One of the things she writes in her autobiography is every time she goes, she never gets used to it. It's appalling, the conditions that women had to experience. It was such a shock to the system to women who were kind of used to a particular way of life and a standard.

All of a sudden, they are the lowest of the low — made to wear these horrible clothes like sacks with arrows written on them. And it's extremely degrading.

I do think she found it difficult to talk about it and certainly to write it down.

In 1913, she was arrested on charges of conspiracy. And we had an act called the Cat and Mouse Act, under which women would go on hunger strike, they would be force-fed, they would get to the point of death, then the government would release them so they wouldn't die in prison and the government would be blamed for it.

So then the women are let out and they're supposed to come back when they're well enough to endure it. But of course they don't — they go on the run.

And so that kind of cycle that Annie Kenney went through in 1913 — hunger strike, force-feeding, release, go on the run, re-arrested — it's incredibly draining and it has a massive impact on her health and well-being for the rest of her life.

- London women celebrating 100 years of getting the vote

- Manitoba women were first to win right to vote 100 years ago

- 95-year-old Toronto woman recalls a time before universal suffrage

How did this letter end up in Canada, in British Columbia?

Two of the sisters moved to Canada — one to Montreal as a teacher, and Nell, the recipient of the letter.

Nell, as I said, was also a suffragette in the U.K., but eventually married a journalist who had rescued another sister from an anti-suffrage mob. And the two of them end up moving to Canada.

A previously unknown letter from Annie Kenney, the first woman imprisoned for campaigning for the vote, is due to go on public display for the first time after being uncovered by <a href="https://twitter.com/UniofOxford?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@UniofOxford</a> historian Dr Lyndsey Jenkins during her research: <a href="https://t.co/UCsIyjT0ij">https://t.co/UCsIyjT0ij</a> <a href="https://t.co/YdTlzXEsHL">pic.twitter.com/YdTlzXEsHL</a>

—@UniofOxfordAnd in Canada, Nell Kenney is known under her married name as Sarah Ellen Clarke. She keeps all her suffrage papers — she has a real sense that this is something important and significant. She gives them to her daughters, who also share that feeling. And so they give them to an archive.

But it wasn't until I was looking into the whole family background that I realized that these two people — Sarah Clarke in Montreal and Nell Kenney in the U.K. were the same person.

What will happen with that letter now?

The letter is on loan to [Gallery] Oldham, where Annie is originally from. The Royal British Columbia Archives have very generously lent it to Gallery Oldham so that people can experience this unique piece of suffrage history for themselves.

Written by Ashley Mak and Kevin Ball. Interview produced by Ashley Mak. Q&A edited for length and clarity.