One of the driest places on Earth struggles to safeguard its most precious resource: water

Leaky pipes, theft and dwindling rainfall threaten Jordan's water supply

This story is part of our series Water at Risk, which looks at Cape Town's drought and some potential risks to the water supply facing parts of Canada and the Middle East. Read more stories in the series.

Inside a high-tech control room that looks ripped from the pages of a spy thriller, specialists train their eyes on a wall of monitors, tracking one of the scarcest resources in the Middle Eastern nation of Jordan: water.

The Ministry of Water and Irrigation regularly flies drones to monitor pipelines. The control centre staff are looking for signs of what has become a serious problem: water theft.

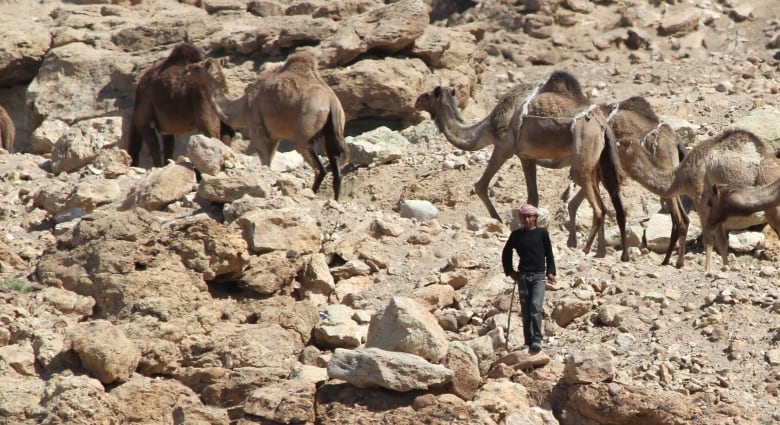

Jordan, one of the driest countries on the planet, sits in the middle of a region where rivers often run dry and water doesn't always flow when taps are opened.

To prevent a water crisis, the kingdom is looking to move past decades of regional animosity as it works to provide water security to its 10 million residents.

"It's something that's always at the back of our minds, something that we need to pay attention to. We can't overuse water," said 15-year-old Michael Sabbagh, who lives in the capital Amman.

Jordan's schools teach water conservation, alongside arithmetic and Arabic. Sabbagh's Grade 10 class recently visited an environmental preserve where guides spoke about water levels in Jordan.

Refugees add to concerns

The country's reservoirs are currently only 60 per cent full, and the reserves will fall as the summer temperatures soar — to highs of 35 degrees Celsius — in a nation where much of the land is desert.

The influx of more than a million refugees from the war in neighbouring Syria has also increased demand by about 20 per cent.

While the government's actions have improved supply, they have not been sufficient to solve the larger problem.

That's why the country's Water Authority restricts the flow of water to communities and towns. Neighbourhoods in Amman, for example, will have water delivered through the pipes for about 12 to 24 hours a week.

That means residents have to scramble to make sure underground cisterns and the ubiquitous rooftop tanks are filled, so there is supply for the rest of the week.

If people or businesses run out, some turn to Rakan Bisharat, who runs a water supply business on the outskirts of Amman. Trucks are loaded at Bisharat's facility, and water is delivered to top up tanks.

PHOTOS | Water worries mount around the world

"In the summertime, the lineup for trucks is about three hours here," he says, pointing to an area where three tankers were being filled. "The demand is so high."

Climate change prediction

Research published last year by Stanford University's Jordan Water Project predicted a 30 per cent drop in rainfall by 2100, along with an increase in temperatures of 6 C. The study forecasts that the number of droughts will double.

Jordan, a resource-poor nation with a weak economy, will need new water sources to keep the taps flowing, so the government has backed an ambitious plan that will see the kingdom partner with Israel, which is well down the road of providing water security for its residents and businesses.

The brine would be pumped into the Dead Sea, where the water level is dropping at more than a metre every year.

"Part of the problem in the Middle East is that we don't trust each other, because of the conflict of so many years," said Hazim el-Naser, who served recently as Jordan's minister of water and irrigation.

"This is a real project to promote peace and regional co-operation among parties in the most troubled area in the world."

But the initiative was halted when diplomatic ties between the two neighbouring countries were suspended last summer after two Jordanians were killed by an Israeli embassy guard who said one of the men stabbed him. Israel has since apologized.

Some experts have said the projected price tag of $10 billion US could triple and worry the project will sink before any water is produced.

Israel's water solution

Jordan would rely on Israel's desalination expertise. Close to 80 per cent of water that flows through Israeli taps comes from desalination plants along the Mediterranean coast.

Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied West Bank face water restrictions similar to those in most Jordanian communities. Palestinian officials say Israel blocks access to aquifers and springs while the Israeli government blames the Palestinians for failing to show up to meetings to discuss the issue.

In the Gaza Strip, a lack of clean water has contributed to what the United Nations has called a "humanitarian catastrophe." Many homes lack stable power to pump water, leaving residents using pails to clean dishes and clothes. Water that comes through the pipes usually comes from the Mediterranean Sea, which is also where most of the enclave's sewage is pumped.

"The water situation is very difficult here," said Gaza resident Rami Larouki. "It's not fit for human consumption."

Swapping sun for water

Turning sea water into potable water takes vast amounts of power. Israel's desalination plants usually only run overnight to take advantage of lower electricity costs.

EcoPeace, an environmental NGO made up of Jordanian, Israeli and Palestinian activists, is floating a new idea to harness the sun-soaked deserts of Jordan, and sell the solar power to Israel and the Palestinian Authority, who would use it to run desalination plants.

"By advancing a water-energy exchange we're creating some stability, we're creating an atmosphere of co-operation," said Gidon Bromberg, the Israeli director of EcoPeace.

Bromberg said all three governments "have expressed support" for the Water & Energy Nexus, which is projected to cost $30 billion. Despite the price tag, "not only is it realistic but it's absolutely essential," given the region's water woes.

Bromberg said the idea could bring wider benefits: "it's certainly stability, it's certainly security, and those are two essential ingredients for peace."

Water at Risk: Read more stories in the series

- Divided to the last drop: Inside Cape Town's water crisis

- 'It's not impossible': Western Canada's risk of water shortages rising

- PHOTOS | Water worries mount around the world

- How Cape Town is weaning itself off water

- Vancouver's water to get scarcer, pricier as climate changes

- Nobody knows what's next for Cape Town's water supply

- What living on 50 L of water a day looks like

- Read all the stories in the series