How highrises can move toward zero waste

Also: Rethinking how we talk about heat

Hello, Earthlings! This is our weekly newsletter on all things environmental, where we highlight trends and solutions that are moving us to a more sustainable world. (Sign up here to get it in your inbox every Thursday.)

This week:

- How highrises can move toward zero waste

- Rethinking how we talk about heat

- Did life on Earth begin on Mars?

How highrises can move toward zero waste

Multi-residential buildings often have pitiful rates of recycling and composting. For example, in Toronto, highrise residents divert an average of 27 per cent of their waste from the landfill — less than half the 65 per cent diversion rate for people who live in houses.

But getting most of the way to zero waste is possible for highrise dwellers, as Toronto's Mayfair on the Green has shown.

The condo building in the Malvern neighbourhood in the city's east end has more than 1,000 residents across 282 units, but manages to divert 85 per cent of its waste to recycling and composting, saving $15,000 a year in waste fees. It now puts out just one dumpster full of garbage a month, down from 20 a month in 2008.

About three years ago, this caught the attention of the Toronto Environmental Alliance (TEA), a local group focused on sustainability.

"We said, 'Wow, this is amazing,'" said Emily Alfred, TEA's waste campaigner. "What are they doing that makes them so successful?"

Often, the biggest challenge for multi-residential buildings is that many were designed before recycling and organics collection existed. Consequently, they make it more convenient to throw out garbage — down a chute just steps away from your unit — than to recycle or compost, which typically requires a trip down the elevator to the basement, garage or even outside across a parking lot. (Plus, in many parts of Canada, organics composting often isn't available at all.)

Because waste disposal is generally handled by building staff, residents are often unaware of how much disposal costs and don't understand the impact of putting waste in the wrong bin, Alfred said.

Mayfair on the Green solved these problems by:

-

Converting their garbage chute into an organics chute (and making people take their garbage, which is less smelly, downstairs).

-

Creating a main floor recycling room to handle a variety of waste, including cooking oil, e-waste, hazardous waste and reusable items that could be offered to other residents before being donated to charity.

-

Doing door-to-door outreach so residents understood proper disposal for each kind of waste.

Alfred said that highrises also have some features that can facilitate waste diversion, such as common spaces that can be used to collect and sort different kinds of waste and house donation bins.

They also have property managers and maintenance staff who can help set up waste rooms, track waste and come up with innovative solutions. One key to Mayfair on the Green's success was its superintendent, Princely Soundranayagam (see above photo), who did all of those things.

Finally, they're communities where residents can share ideas and some of the work involved. That, Alfred said, "can be really powerful in terms of creating a zero waste culture in a building and helping it move forward."

TEA has spent three years working with Mayfair on the Green, as well as 10 other highrises and University of Toronto geography professor Virginia MacLaren to learn how to replicate this success in other buildings. TEA is inviting other buildings to take part in the next phase of its Zero Waste Highrise project, which launched this week.

The group will help participants evaluate their building, develop a plan and report on their progress. It will also provide inspiration in the form of success stories and learning events.

While the program itself is focused on Toronto, Alfred said many of the group's lessons and resources are universal, and highrise residents in other cities across Canada are welcome to try them out.

— Emily Chung

Reader feedback

Helen Hansen wrote in to say, "It riles me a bit that people who talk about buying or using an electric car think they're doing their bit. Where's the electricity coming from, and is the buyer/user going to fill that car with three-four people? Let's promote and use public transportation, which isn't adequate in many places in Canada, and where it is, it's too expensive, like where I live in Guelph, Ont."

Write us at whatonearth@cbc.ca.

Old issues of What on Earth? are right here.

There's also a radio show! Make sure to listen to What on Earth on Sunday at 10:30 a.m., 11 a.m. in Newfoundland. You can also subscribe to What on Earth on Apple Podcasts, Google Play or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also listen anytime on CBC Listen.

The Big Picture: Rethinking how we talk about heat

Extreme weather influenced by climate change is becoming ever more common. But a couple of years ago, Arran Stibbe, a professor of ecological linguistics in the U.K., noticed that as a culture, we tend to ascribe more negative descriptors to wet weather than to dry. Meteorologists talk about "the risk of a shower" or "the threat of rain" while heralding a period of hot, sunny weather as "glorious" — when, in fact, extreme heat kills more people every year than any other type of extreme weather. "This is a story that is embedded deeply in our minds, that sunny weather is good and every other kind of weather is bad," Stibbe recently told the environmental site Grist. The result, according to one researcher, is that heat is "massively underreported" as a health threat.

Hot and bothered: Provocative ideas from around the web

-

Given slumping fuel demand and intensifying calls for climate action, petroleum producers are on the back heel. But there is still money to be made in plastic. A New York Times investigation found that an industry group is lobbying the U.S. government to force Kenya to not only weaken its plastic ban but also import more plastic waste from other countries.

-

A couple of Italians who believe the Earth is flat headed to the southern island of Lampedusa, which they think represents the physical end of the world. They took a boat to get there, but because of a navigational mishap, ended up on the island of Ustica instead — where they were put in quarantine, no closer to proving their belief that the Earth is a giant disc rather than a globe.

-

Despite its downsides (most notably, storing radioactive material), nuclear energy is likely necessary in the effort to decarbonize the planet. Proponents have talked about the potential of small modular reactors, which could be assembled in a factory and deployed rather quickly. Well, a design by American company NuScale is the first to receive approval from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Did life on Earth begin on Mars?

How life arose on Earth remains a mystery, although many theories have been proposed. Now, a new study by Japanese scientists has reinvigorated the discussion around panspermia — that is, the idea that life may have reached Earth from elsewhere.

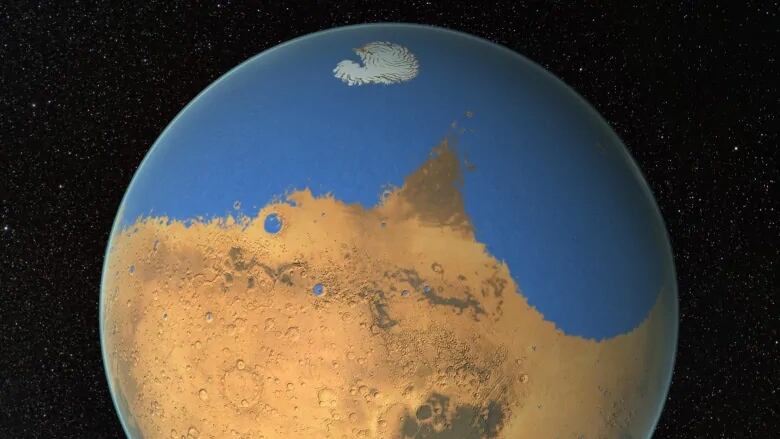

The panspermia hypothesis suggests that bacteria travelling through space, hitching a ride on a piece of rock or other means, eventually made its long-distance journey to Earth. Mars is a particularly appealing source, as studies suggest it was once potentially habitable, with a large hemispheric ocean.

However, the biggest challenge has been determining if bacteria could survive the journey. To answer that question, a group of Japanese scientists, in collaboration with the Japanese space agency, JAXA, conducted an experiment on the International Space Station.

In the new study, published late last month in the journal Frontiers of Microbiology, researchers found that with some shielding, some bacteria could survive harsh ultraviolet radiation in space for up to 10 years.

For their experiment, the team used Deinococcal bacteria, well-known for tolerating large amounts of radiation. They placed dried aggregates (think of them as a collection of bacteria) varying in thickness (in the sub-millimetre range) in exposure panels outside the space station for one, two and three years beginning in 2015.

Early results in 2017 suggested the top layer of aggregates died but ultimately provided a kind of protective shield for the underlying bacteria that continued to live. Still, it was unclear whether that sub-layer would survive beyond one year.

The new three-year experiment found they could. Aggregates larger than 0.5 mm all survived below the top layer.

Researchers hypothesized that a colony larger than one millimetre could survive up to eight years in space. If the colony was further shielded by a rock — perhaps ejected after something slammed into a planet such as Mars — its lifespan could extend up to 10 years.

Akihiko Yamagishi, a professor at Tokyo University in the department of pharmacy and life sciences who was principal investigator of the Tanpopo mission designed to test the durability of microorganisms on the ISS, said one of the important findings is that microbes could indeed survive the voyage from Mars to Earth.

"It increases the probability of the process," Yamagishi said in an interview. "Some think that life is very rare and happened only once in the universe, while others think that life can happen on every suitable planet. If panspermia is possible, life must exist much more often than we previously thought."

There are two important factors, he believes: Mars and Earth come relatively close together in their orbits every two years, which would allow time for transfer of bacteria; and the RNA world theory.

This theory hypothesizes that Earth was once composed of self-replicating ribonucleic acids (RNA) before deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and other proteins took hold. Yamagishi believes that RNA could have once existed on Mars before conditions for life arose on Earth and potentially travelled toward Earth, bringing along RNA that began to seed our planet.

This isn't the first experiment to see whether bacteria could survive in space. While some research suggests bacteria could survive a trip embedded in rock, this is the first of its kind to suggest they could survive without that kind of aid, what the researchers term "massapanspermia."

However, it's not an open and shut case.

"Actually proving that it could happen is another thing, so I wouldn't say that this is ironclad proof," said Mike Reid, a professor at the University of Toronto's Dunlap Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics who wasn't involved in the Japanese study.

Does Reid believe life could have made its way from Mars to Earth?

"If you'd asked me 20 years ago, I would have said no, of course not. But now, it's a little hard to say," he said. "I think we won't be able to answer that question until we've had a really thorough look at the surface of Mars ... did it ever have life ... and was it like us?"

— Nicole Mortillaro

Stay in touch!

Are there issues you'd like us to cover? Questions you want answered? Do you just want to share a kind word? We'd love to hear from you. Email us at whatonearth@cbc.ca.

Sign up here to get What on Earth? in your inbox every Thursday.

Editor: Andre Mayer | Logo design: Sködt McNalty