Missing patients, illicit drugs in Vancouver hospital

Patients' families, staff and police say facility substandard

Patients' families, staff and police are sounding the alarm about a lack of security in a psychiatric facility at Vancouver General Hospital.

"My daughter escaped many, many times," said Susan Ackerman, whose mentally ill daughter has been committed to the hospital several times. "It’s a very unsafe facility for her."

Carmen Daly said her mentally ill son also walked out numerous times. She said he would show up at home in the middle of the night in a hospital gown with his bare feet bleeding.

"He is one of the ones that run away all the time," said Daly. "He is scared. My son is scared of everything. They just gave him pills and treated him like a dog."

The psychiatric units are in a building that is 70 years old and not designed for treating patients with mental illnesses. They have to share a room with three others and they have no privacy. The facility has poor ventilation and no secure outdoor space.

"This building is falling apart," said Lorna Howes, director of mental health services for the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority. "The building envelope has failed."

Many of the patients were brought there by police and were then committed — deemed a threat to themselves and others. Even so, the front and back doors are propped wide open. The only place patients can get fresh air is out on the public street.

"Patients can just walk away," said Howes. "Quite often people will take the approach of saying, ‘I am out of here. I’m gone.’ Then the police are called and the police are asked to go and find them and bring them back — because they are at risk."

Drug dealers walk in

None of the units are locked. Staff and families say drug dealers also walk right in to deliver cocaine and methamphetamines to patients who use the drugs on the open wards.

Ellen Wiebe, a medical doctor, was shocked when her cocaine-addicted mentally ill son was able to keep doing drugs while in VGH.

"He was supposed to be on the locked ward and he was supposed to be protected and he was proven to have gotten cocaine on the ward," said Wiebe.

Her husband, Allan Oas, said his son also walked out of the hospital and turned up at home, at a time when his parents were actually frightened of him.

He’d been sent to hospital because he’d seriously injured himself, trashed his parent’s home and didn’t know who they were.

"[VGH] is a scary place to be, and even if you are psychotic and delusional, you actually make an intelligent decision and you try to get out as fast as possible," said Oas.

One psychiatrist who has had many patients in that hospital said the access to street drugs makes it impossible for people to get better.

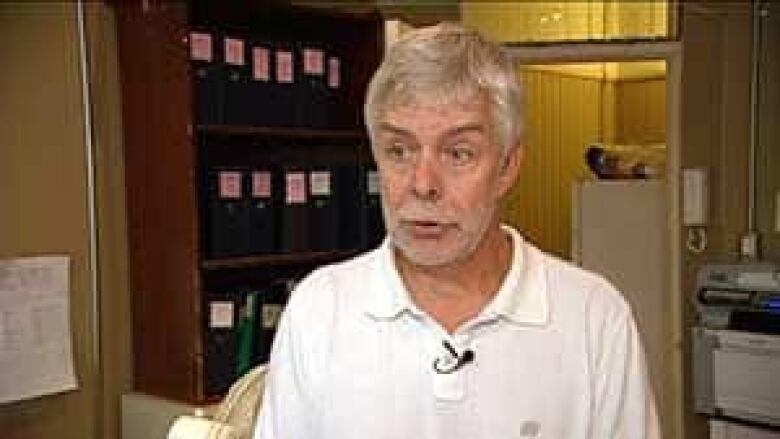

"You’ll have people coming in posing as a pizza delivery man. He just drops a piece of paper that has either heroin, crack cocaine, methamphetamine in it and now the perimeter of your unit is breached," said Dr. Bill MacEwan.

He said the problem is made worse in an unsuitable facility like VGH, where patient rooms are crowded and doors are wide open.

"These are the drugs that make somebody’s illness much worse. They will stimulate psychosis, agitation, aggression — and so if you have those drugs on an open psychiatric unit all bets are off," he said.

MacEwan believes at least part of the building should be locked.

"Part of the reason you have a locked door is to keep individuals in, who are needing care," he said. "Part of the other reason is to keep people out."

Howes admits drugs are brought in easily, but said that would all change, if and when a proposed new facility gets built. The health authority has been lobbying the province for months, to contribute $42 million to a new building, a plan that has been in the works since 2002.

"Right now there’s so many doors that come into that building that you couldn’t possibly imagine — you could have five security guards in that building and you could not control who was coming in," said Howe.

She admitted the access to street drugs is hurting patients.

"This is a vulnerable population and when they are psychotic they are even more vulnerable."

Suicides reported

A draft 2010 report by Vancouver police obtained by CBC News — which police are now releasing — shows staff at VGH called police more than 100 times last year to report patients missing.

It said, in the first half of the year, three patients committed suicide after walking away from treatment there.

The report, titled "The Disturbing Truth," said the security problem "consumes resources, frustrates police, and, in some cases endangers the lives and safety of patients, front-line police officers, other first-responders and the public."

"The attempts of police to solve these "problems" are still being hindered by the barriers of information sharing, lack of system capacity and a lack of apparent will on the part of health system in Vancouver to adapt and change in order to work effectively with the VPD to truly solve these issues in a constructive and sustainable way," read the draft report.