Tintin in America defended by freedom to read advocates

Hergé's Tintin in the Congo faced challenges over its racist stereotypes of Congolese people

Tintin in America is having a rough week in Canada.

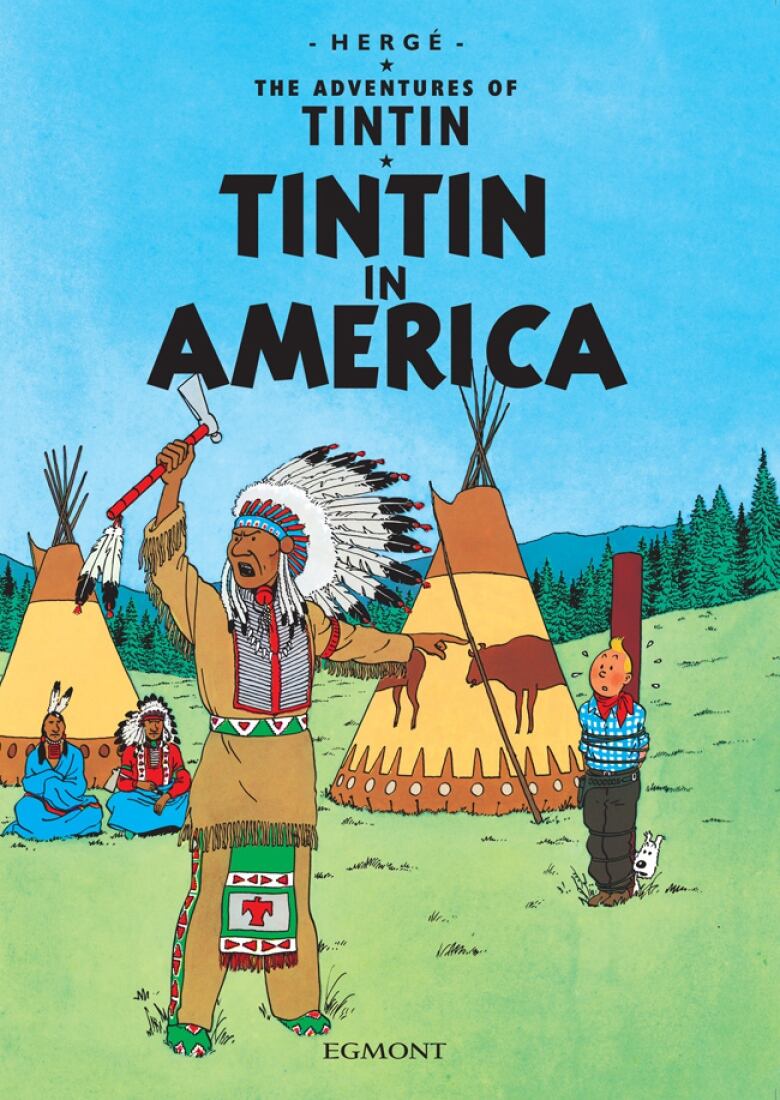

Not everyone's a fan of how the 1932 comic splashes aboriginal stereotypes across its pages. On the cover, for example, one chief wears buckskin and wields an axe while "paleface" Tintin is tied to a pole in the background.

- Winnipeg Public Library pulls Tintin in America off shelves pending review

- Winnipeg Chapters temporarily pulls Tintin comic over racism complaint

Last weekend, a Winnipeg bookstore pulled the comic after a complaint from a First Nations educator about some of the implicit racism in Tintin tales. Chapters reversed the decision shortly after.

Those collections were removed about two years ago, but Tintin in America reappeared as part of a re-order process in the last year, a city spokesperson told CBC News.

"In 2013, this research collection was disbanded in part due to a changing mandate of the library (not archival in nature) [and] lack of use," the spokesperson said. The idea that other libraries, like those in universities, might be more suitable environments for these research collections also played a role in their 2013 removal, the spokesperson said.

And this week, the city once again removed the book temporarily, perhaps permanently, pending a review.

The city has the highest urban population of aboriginal people in any Canadian city and has suffered strained relations between indigenous and non-indigenous people.

But out of sight, out of mind may not be the best policy for offensive literature, say those who defend the freedom to read.

"We want to fight this kind of censorship — the removal of books — because somebody disapproves of the content," says Deborah Caldwell-Stone, deputy director of the American Library Association's office for intellectual freedom.

That's the office that runs the association's annual banned books week.

"Everyone has the right to make up their own mind about what they're reading," she says, "and have access to those ideas."

Long list of challenged books

In Tintin's case, it is one of many books written decades ago that have come under fire for their depictions of minorities.

It's also not the first time modern-day readers have questioned the work of Tintin author and cartoonist Georges Remi, who went by the pen name Hergé.

In 2012, a Belgian court heard a case requesting publisher Moulinsart withdraw Tintin in the Congo from bookstores for its depiction of Africans. The court ruled against the proposed ban.

Everyone has the right to make up their own mind about what they're reading and have access to those ideas.- Deborah Caldwell-Stone, American Library Association

In a somewhat similar vein, there has often been criticism of Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House books, published in the 1930s and early '40s, for portraying Native Americans as dangerous savages.

Mark Twain's classic Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, published in the late 1800s, is also no stranger to controversy for its portrayal of a black slave, Jim, and use of derogatory language.

Even modern-day books have been targets. Other authors petitioned to have David Johnston revoke Canada Reads' semi-finalist When Everything Feels Like the Movies from the Governor General's Literary Award for best in children's literature because they felt it was too vulgar.

When children (and some adults) started obsessing over J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series, some parents sought the books' removal from schools, saying they promoted witchcraft.

The American Library Association tracks frequently challenged books in the states, while Canada's Book and Periodical Council does the same through its project, Freedom to Read week.

It takes extraordinary circumstances for those two organizations to be onside with a book ban. The text must be illegal, like one containing child pornography or one that attempts to incite hatred against a group of people.

From their perspective, Tintin in America doesn't quite meet that criteria. In fact, there may even be some benefit to it.

Hergé published the comic to entertain, says Franklin Carter, editor and researcher for the Book and Periodical Council's freedom of expression committee, in an email to CBC News. His stories have been so popular that they are available in more than 100 languages.

He gave readers "a rollicking good story," Carter says, and adults shouldn't be prevented from enjoying it.

Also, academics may want to examine Hergé's texts for research on graphic novels, children's literature or native studies. Teachers might need them to prepare lessons on the historical representations of minorities.

They also offer the opportunity for all readers to learn about historical stereotypes and changing perceptions.

Book banners usually have good intentions

The people who are concerned about these books being widely available are often well-intentioned folks, says Caldwell-Stone. They fear children who get their hands on controversial literature may not have the knowledge to understand it in context.

Education, not censorship, is the key to social progress.- Franklin Carter, Book and Periodical Council

But, there are ways to offer kids the right context without removing the books from circulation, she says.

She suggests libraries stock books that analyze a controversial text to help readers contextualize it, and talk to parents and kids about the meanings behind the content.

Librarians can also move certain books to adult sections to prevent unassuming children from picking them out, says Carter. An American bookstore chain moved Tintin in the Congo out of the children's section in 2007.

If there's interest, librarians can also hold seminars for adults about stereotyping in books.

"Education, not censorship, is the key to social progress." says Carter.

Teacher education is critical

It's up to parents and educators to have discussions with kids about what they're reading, the defenders of controversial books say.

Teachers must be trained to have these conversations, says Jo-ann Archibald, the director of the University of British Columbia's indigenous teacher education program.

All future teachers attending UBC take a semester-long aboriginal education course. They learn about how to critically discuss aboriginal issues with students, including analyzing stereotypical texts.

With guidance, kids can then examine the impact of racist imagery and understand why they're considered offensive in the modern world, she says.

But Archibald recognizes that not all teachers have received this type of training, and not all students have access to informed adults.

"It is problematic if the child is not able to understand why there are issues."