Transcript 2: Robert Fowler interview Sept. 9, 2009

Canadian diplomat speaks with Peter Mansbridge about his time in captivity with al-Qaeda, an emotional phone call home to his wife and his eventual release

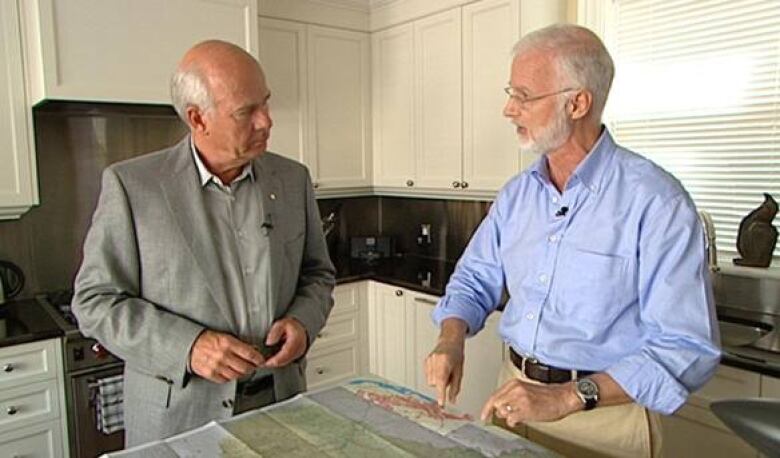

This is the second of a two-part interview by CBC's chief correspondent Peter Mansbridge with retired Canadian diplomat Robert Fowler. It aired on The National on Wednesday, Sept. 9, 2009. The first part, which aired the previous day, can be read here .

MANSBRIDGE VOICE-OVER: Tonight the conclusion of Robert Fowler's amazing story of survival inside the world of al-Qaeda.

Last night, one of Canada's most experienced diplomats told how he, along with his assistant Louis Guay, were both kidnapped while on a special mission for the United Nations in Niger. And how, within days he was being paraded before al-Qaeda cameras, convinced he would be executed at any moment.

Tonight, how freedom came after 130 days and raising the question of ransom. Did someone pay for Robert Fowler's freedom? But first, living with al-Qaeda: What was it like to sleep, eat and be on the run with the world's most feared terrorist organization?

Living with al-Qaeda

MANSBRIDGE: Food, water. What did you eat? What did you drink?

FOWLER: We drank all the water we wanted. The water was from desert wells. Only once did we ever camp at a well, and that was only on part of that crash north and for a couple of hours. But obviously wells are where other people come, and they didn't want that.

It's where their enemies might be looking for them, and they didn't want them. So they would send a water mission out and come back with usually 45-gallon drums and plastic things filled with water, often tasting of whatever had been in the drum, and many of the drums have that nice triangle with the skull and cross bones. And there were more than a few occasions in which I couldn't drink the water.

MANSBRIDGE: Because of the taste?

FOWLER: Yes. I would gag and it would come up. I mean, now and then you'd see little things swimming in the water. That didn't bother me. I thought, one can deal with that, and it wasn't the fact that it was poisonous. It was the fact that I couldn't get it down. And then you'd go Oliver-Twist-like and say, please sir can I have some other water?

Food — we didn't eat, see a fruit or a vegetable in one period of 85 days. We ate rice and pasta —short, dried pasta.

MANSBRIDGE: Not like the pasta you saw when you were ambassador to Rome?

FOWLER: Not quite, no. Not quite. We, there would be often a single can of tomato paste for 28 of us in the pasta.

MANSBRIDGE: So you were all eating and drinking the same?

FOWLER: Not in the same place, but the same. They would not eat with us as infidels, which of course suited us just fine. So, rice or pasta, sometimes a sheep or a goat. Once a camel that we ate for 17 days. They'd immediately dry it and hang strips on the trees and in that climate it would dry instantly.

MANSBRIDGE: How did that taste?

FOWLER: Camel, it was actually pretty good. Mind you, any meat was pretty good. We knew that we desperately needed protein and we just weren't getting it.

So the food — at one point they gave us a sort of a lentil soup, and I, hoping to encourage better behaviour, said, wow, that was good. That was really good lentil soup, and they snarled at me and said, "We eat to survive, not for pleasure." So they weren't a very joke-y crew.

MANSBRIDGE: At no point in the four-plus months did they torture you or try to torture you beyond the fact that they were holding you at gunpoint?

FOWLER: Correct.

MANSBRIDGE: There was nothing like that?

FOWLER: They did not. They, I, I had absolutely no doubt that there wasn't one of them who would have slit our throat at the order. But up until that point, we were not abused.

MANSBRIDGE: Did you ever feel any attachment to these guys, you know what I'm getting at?

FOWLER: Stockholm stuff and …

MANSBRIDGE: Yeah.

FOWLER: Uh, no, but there was, no. There was very little connection. I mean they lived in a world that I can't understand. I can understand it intellectually, as I've been trying to explain, but none of those values are values that I could, could get close to, could — I mean there was no fun, there was no love, there was no joy.

At one point, Louis and I, after we had talked about everything we could have conceivably talked about, um, we decided to sing and we are both not singers! But we sang songs, remembered songs and they came running over, "You stop that right now. We're not going to have any of that happy singing. It's unacceptable."

What I guess I'm saying to answer your question, there wasn't, there wasn't, there wasn't enough common ground to be friendly.

The phone call home

FOWLER: It was without a doubt the most dramatic moment, the most emotionally acute moment of the thing. But basically we were told on day 85 that we would be able to speak to our families.

MANSBRIDGE: Had you been asking for this, or this just came out of the blue?

FOWLER: Out of the blue. No, we had not been asking for it. They clearly had an agenda and their agenda was, uh, tell your families to mobilize interest in support for and get things moving, and they were very explicit about that's what they wanted out of this call. And I was perfectly happy to, I think I would have agreed to anything to speak to Mary.

And I, at this point we're at day 85, 87, I wasn't at all sure we would ever come out of this at all and I wanted to say goodbye, I wanted to say the things that were important. So they said you're going to speak to your wives. It's all been arranged.

We then drove 19 hours to the biggest damn sand dune you have ever seen, 40 kilometres on the Algerian border. And we made stops along the way, and this was late at night, which I hadn't planned on.

There are four cars down at the bottom on the dune, lights on, heavy machine guns mounted on the four points, and then along the razorback dune are standing six of us with Belmokhtar, the head of the group according to various websites, you know, the king of al-Qaeda in the southern Sahara, and Omar, the kind of hostage liaison was there and, and they have their cellphones.

So the trick is we're not using the [satellite] phone, which they know can be located, they're using a cellphone catch, from the height to catch the Algerian cell net. So, we we're up there and I'm first and I can phone Mary. My first thought is I couldn't remember the phone number. I couldn't remember any phone numbers. But I did, so I called here and there was no answer with my miserable voice saying, "Leave a message!" So then I called Mary.

MANSBRIDGE: Did you leave a message?

FOWLER: I did leave a message actually! I did. Then I called Mary's cellphone, and I saw, I saw in my mind her rummaging through her pit of despair trying to find the damn cellphone and I knew she wouldn't before I got her message saying leave a message.

Then some, one of them said, "Send her an SMS so she has it." She can show you. So I got out the thing and I did: "Darling, Mary, I love you." I hacked out the SMS and sent it, which she got. And she, her first thought was, he's free. I mean I didn't say I was free, darling Mary, oh please call this number, because I'd asked them, "Listen, instead of leaving these messages, tell me, let me leave a message saying call this number." They said we don't know what this number is! So I don't know if that's true or not, or whether it's security; we don't know. But it doesn't matter anyway, because your phone will show …

MANSBRIDGE: On the SMS.

FOWLER: … the number. I didn't, by the way. But please call this number. So Mary got that and terribly frustrated, etc., there. But I'd struck out for three.

Louis calls. Louis calls home, leave a message. Calls Maya's cell phone, leaves a message. They say, "Oh! oh! No more power. The phone's dead, no more power."

So the phone gets trotted down the hill, plugged into the battery and they're reviving up the phone, recharging the battery. They bring it back up saying, wonderful, we got the phone. I start dialing the number again and the thing comes up and says there's no more credits in the phone.

Phone goes back down the hill, the media guy gets onto his laptop and he calls his buddy, I mean he emails his buddy somewhere in Nigeria saying take up the phone. So this guy then buys the appropriate credits with whatever credit card so that this phone gets re-, and then up, up it comes again.

MANSBRIDGE: You must have thought you were in the middle of a comedy here?

FOWLER: It was so …

MANSBRIDGE: Were people laughing?

FOWLER: Uh, no.

MANSBRIDGE: I mean in spite of the situation.

FOWLER: No, they weren't. There was a lot of frustration going on, on all side, on all sides. So anyway the phone comes back up with a charge and with new credits. I phone again and I get Mary and I say what I have to say, and then I say then — and Mary was absolutely fantastic — and then I was getting into the goodbyes and she gave me hell. She said, "What do you mean goodbye? You're coming home. We've got lots of things to do. Don't give up, don't be silly." And I said, "Well, you know, I mean our grandson's birthday was day 100," which worked out was in two weeks. They said, we'll have you home by then, and I course knew that she is a remarkable woman but it is not necessarily within her power to bring me home from there in 13 days!

But nevertheless it was, it was great, her straightening me out.

The power of hope

MANSBRIDGE: If somebody had told you before this had started you were going to be there for that many days under those kinds of conditions …

FOWLER: Would I have thought?

MANSBRIDGE: That you could do it?

FOWLER: If they had told me you're going to be there for that long under those conditions and it will be all right in the end, the answer is yes. I think, yes.

MANSBRIDGE: But you had to believe — with very few exceptions from what you tell us — that it was going to be all right.

FOWLER: No. If I've said that, I've misled you. I was never convinced it would be all right. I wasn't convinced it wouldn't be all right, except for the couple of instances I mentioned. But I never felt confident that this will work out well.

MANSBRIDGE: But you were hopeful?

FOWLER: Of course I was hopeful, and there were days when the hope was strong, and there were days when the hope was weak.

MANSBRIDGE: But you never gave up hope?

FOWLER: No, I never gave up, but I was, but there were deeply depressing moments when, I don't know, is a depressing moment a place where hope fades rather sharply.

MANSBRIDGE: Did you pray?

FOWLER: I'm not a praying guy, Peter, personally. Louis is a religious guy, and every now and then I'd ask him if there were any messages for me, but, uh, you know you think about what's important. You think about family, you think about, you know, all of the things that you didn't do that you would have done and you should have done, and wished you had done. And you think you know what a crazy end. But no, I never gave up hope.

Freedom

MANSBRIDGE: Why did they let you go?

FOWLER: I'm in the very happy position of saying, I don't know. And also of course, being there, back to Louis, I wasn't involved in the negotiations. So, while at least in theory I could speculate on how I might have got out, I'm not going to do that. I did say earlier, I didn't get out because I was a nice guy. And they are not in the business of humanitarian gestures.

MANSBRIDGE: Exactly.

FOWLER: So, but, beyond that, who did what? How? Where and for whom? I don't know.

MANSBRIDGE: But we assume going into this that they were looking for recognition and that an organization like that needs money.

FOWLER: Yes. And the Internet is full of discussion about them wanting prisoners released. So, I think you've got the elements of the issue there and what, which, beyond recognition if any of those elements that were satisfied, I don't know.

MANSBRIDGE: But would it surprise you if any or all of those were met? In fact, at the end of the day, they gained?

FOWLER: I, would it surprise me if they gained? I mean, they got something. I don't know from whom or how. Prime Minister Harper has said very clearly that Canada paid no ransom. I have absolutely no reason to believe he was misstating the fact.

MANSBRIDGE: But you know how money can move around through any number of different drops to get up?

FOWLER: Yeah. But Peter, I will not speculate on that.

The war on terror

MANSBRIDGE: Did this experience, Bob Fowler, living with al-Qaeda, did it change the way you see our role, Canada's role?

FOWLER: I don't know if, you know, but I'm on record prior to this adventure on Afghanistan, and I don't, I cannot object to the objective in Afghanistan, but I just don't think in the west that we are prepared to invest the blood or the treasure to get this done.

MANSBRIDGE: Did this reinforce that view?

FOWLER: Yes, it did. And it's more than blood and treasure, because it's also, it's not just commitment and the wasting of our youth and the enormous, enormous cost in difficult financial times, it's to get it done we will have to do some unpleasant things. I mean some deeply hard, this isn't, this is not a nice war.

MANSBRIDGE: But is it worth doing?

FOWLER: That's the issue. I mean, I have, I think in other places and times, I have pointed out, I can show you a lot of places in this world where you can put girls in schools without killing people. It's a noble objective, Afghanistan, but a lot of people have tried it before.

I mean, if you in the abstract, Peter, asked me to define a more complex, challenging mission, I couldn't do it. Afghanistan is about as far as Canada's ken as anything I can think of. The culture is as foreign to us as anything you can imagine.

There isn't enough to go around and in our 6 billion there are a billion happy rich people and there are a billion desperately miserably poor people and 4 billion people in the middle who are a lot closer to the bottom billion than the top. We don't have nearly enough money and energy to deal with a tiny proportion of that misery. And therefore it strikes me as rather extreme that one goes out and looks for particularly complex misery to fix. There's lots of things to fix that can be done more efficiently and probably more effectively.

MANSBRIDGE: We're going to leave it on that. Thanks very much.

FOWLER: Not a bit, not a bit.

MANSBRIDGE: Robert Fowler is now at home with his family in Ottawa, writing a book and still wondering whether he'll ever travel to Africa again. Louis Guay is preparing to return to work at the Department of Foreign Affairs.

There is a lot more to this story, and we'll have some of it on the season debut of One on One this weekend.