Teachers, parents say loneliness, isolation eroding student mental health in pandemic year

'Very heightened level of need' in Ontario for mental-health supports, says Compass clinical manager

This story is part of a CBC News series examining the stresses the pandemic has placed on educators and the school system. For the series, CBC News sent a questionnaire to thousands of education professionals to find out how they and their students are doing in this extraordinary school year. Nearly 9,500 educators responded. Read more stories in this series here.

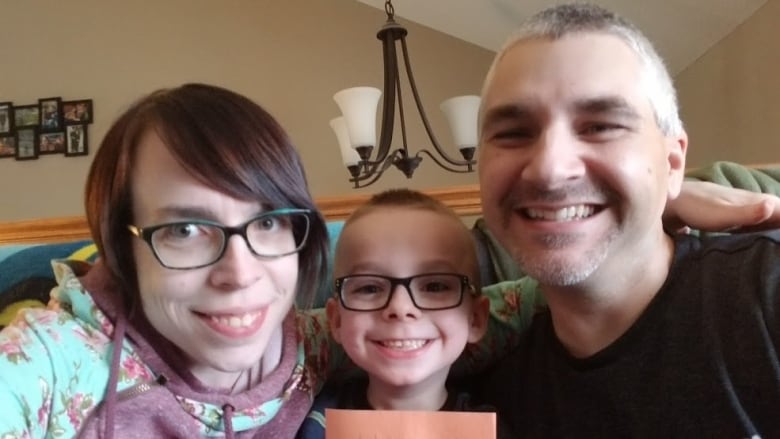

Laurie Lachapelle says her seven-year-old son Penn was loving school this year, but his mood and mindset have taken a "huge nosedive" since Sudbury-area schools closed in early March and he transitioned to learning from home.

"He still has good days, but you know he's a lot more prone to emotional outbursts, he's a lot clingier to my husband and I, and he's just not always the same happy and cheerful little boy that he was when he was able to be in school with his peers," said Lachapelle.

She's particularly worried about Penn, since he's an only child and lacks in-person social interaction.

"My heart breaks for him because you know, I can tell he's really lonely."

The pandemic's effect on youth mental health concerns parents like Lachapelle and educators, as indicated in a CBC questionnaire about the pandemic's effect on education. The survey received responses from more than 9,000 educators across eight provinces. Of those, 159 in northeastern Ontario gave their views, and more than 90 per cent of teachers said they believe the challenges of the school year will have a psychological impact on some students.

Educator responses

Dozens of northeastern Ontario educators also included anonymous comments in their questionnaire responses which that reveal deep concern for students' mental well-being during yet another disrupted school year.

"The social and psychological impacts the pandemic is having on students will far outweigh any academic issues they will have," wrote one teacher. "I spend more of my time being a counsellor than I do an actual teacher this year. And teachers have little support themselves. It's been a very tough year."

Another educator's "biggest concern is around students' physical, emotional, social and psychological health. They present far greater risk factors than [COVID-19] for the students. These are the things that keep me up at night."

'Heightened level of need'

Heather Haynes has seen the pandemic's toll on young people first hand. She's a clinical manager at Compass, an organization that provides mental-health services to children and youth up to age 18 in northeastern Ontario.

When the province went into lockdown and students were sent home from school in March 2020, Haynes expected an increase in young people seeking mental-health support. She was surprised at the dip in demand between March and September that year.

"But once school resumed in September, things started to pick up, and by Christmas time things had really escalated in terms of the demand for service," said Haynes.

Haynes said Compass has seen an increase in demand for services and in the acuteness of need.

"Those who are requesting services are at a very heightened level of need. A lot of the young people that we work with had been admitted to hospital or they'd been seen at HSN [Health Sciences North] through the crisis services, and then referred to us for followup."

Haynes said that throughout Ontario, the demand for services is far exceeding capacity, with those needing help most prioritized. But that means for young people with less urgent mental-health concerns, it's not always possible to intervene early.

Missing social interaction, structure

Haynes believes children's mental health has taken a hit for reasons including social isolation, academic pressures, and the effects of stress and pressures within the household.

Haynes said teenagers seeking help are dealing with challenges related to mood, anxiety and family conflict, while those in the eight- to 12-year-old age range or so are most commonly dealing with behavioural difficulties, like acting out and externalizing anger.

Sudbury parent Stephanie Donnelly said even when her children were at school in-person this year, there were challenges, particularly for her son.

"I don't know if I would say that they were absolutely thriving. Like my son has anxiety issues, so the switch from kindergarten to Grade 1, plus all the extra restrictions … sort of compounded some issues he was having. Even with in-person learning, it was rare he would make it through a week at school without needing to come home because he was so stressed out."

But Donnelly's concerns for her children have grown since schools were closed in early March. She said she worries about behavioural changes in her daughter, who is in Grade 3. While doing well academically, her daughter spends a lot of time in her room and isn't sleeping as well.

"Her little personality isn't quite as sparkly as it normally is," said Donnelly. "Normally there's a lot more giggling and smiling and … that hasn't been sort of the same. It's not like it never happens, but it's definitely less than it was before. So that has me a bit concerned."

Donnelly said she believes her children would benefit most from spending time with their friends, and their mood and behaviours would improve.

Haynes agrees a return to socialization would greatly benefit young people. Although she believes some students will deal with some longer-term mental health impacts, she expects most will rebound.

"I think that overall as we return to a new normal I suppose, when we're back in school for example and parents are perhaps back in the workplace, that typical routine, structure, predictability, patterns, will go a long way to supporting the mental health of young people."

Methodology: How did CBC gather educator responses?

CBC sent the questionnaire to 52,351 email addresses of school workers in eight different provinces, across nearly 200 school districts. Email addresses were scraped from school websites that publicly listed them. The questionnaire was sent using SurveyMonkey.

CBC chose provinces and school districts based on interest by regional CBC bureaus and availability of email addresses. As such, this questionnaire is not a representative survey of educators in Canada. None of the questions were mandatory, and not all respondents answered all of the questions.