The straight poop on disposable diapers, from cloth alternatives to a recyclable future

Billions of diapers are sent to landfill every year. Is there a greener way?

Waves of Change is a CBC series exploring the single-use plastic we're discarding, and why we need to clean up our act. You can be part of the community discussion by joining our Facebook group.

The memory of a maternity ward nurse showing me how to wrap a tiny diaper around my newborn daughter seems almost laughable to me now. It seemed such an intimidating task.

Fast forward two years, and I feel as though I have gone through those motions thousands of times.

In fact, I have. If one baby averages five diaper changes a day, that's 1,825 changes a year, and 4,563 changes by the time they reach 2½ years old and are (fingers crossed) in the throes of toilet training.

Multiply 1,825 changes each year by all the babies and toddlers out there, and the result is a soggy, stinky mountain of diapers.

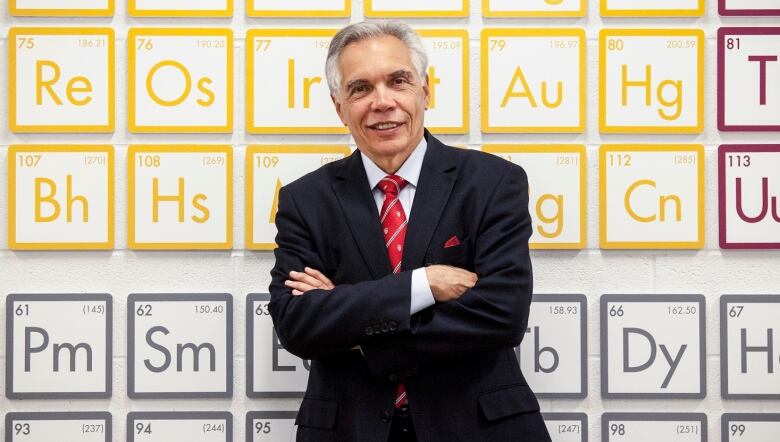

"The volume is fantastic," says Joe Schwarcz, a professor of chemistry and director of McGill University's Office for Science and Society.

"We're disposing something like 30 to 40 billion diapers every year into landfills in North America. That's a huge amount of diapers."

It's also a huge problem for a society coming to terms with its single-use plastic dependency.

The bad news? Babies haven't stopped pooping. The good news? Adults haven't stopped innovating.

The diaper breakdown

Disposable diapers have come a long way since they were first invented in the late 1940s, and the modern-day product is "actually quite an interesting and complex concoction," said Schwarcz.

Its outer layer is typically a plastic — polypropylene or polyethylene — while its inner layers often contain an absorbent fibre derived from wood pulp. But the real star of the show, according to Schwarcz, is what's mixed in with that fibre: a polymer called sodium polyacrylate, "which just has an amazing ability to absorb moisture."

Exact formulations of these plastics and polymers are tightly guarded trade secrets in a competitive and lucrative industry, but they share a common fate: once disposables are sent to the landfill, they stay there.

"In theory, there are biodegradable parts [of diapers]," said Schwarcz. "But the fact is that biodegradation takes place only under perfect conditions, not in a landfill."

Building a better diaper

To the diaper industry's credit, companies have worked to reduce the amount of non-perishable material they use.

One study — conducted by Procter & Gamble, the makers of Pampers, but verified by what they called "external experts" — stated that the company's average American diaper in 2010 weighed 45 per cent less than its 1992 version.

But that same study found innovation slowed from 2007 onward, saying "it is hard to make a small diaper smaller."

For all their efforts to reduce their products' environmental footprints, the Pampers study and others concluded the majority of a disposable's environmental footprint comes from its creation rather than its landfill afterlife, as is commonly believed.

"Used diaper waste causes caregivers concern because they see much of it," stated the Pampers study.

Disposables 'a kick in the teeth'

That's a concern Heather Osmond can relate to.

The cost savings initially attracted the Corner Brook, N.L., mom and her husband to try cloth diapering their son Nolan, after using disposables when he was born and realizing the legacy that would leave behind.

"My child's diapers would literally be here longer than my great-great-grandchildren," said Osmond. "It was almost a kick in the teeth to realize how long our garbage was going to be sitting around."

Osmond threw herself into reusables, using them exclusively until Nolan was fully toilet trained at around 3½ years old.

"His diapers that started at the very, very beginning with him being 10 weeks old lasted him right up until potty training. That was amazing," she said.

Cloth pros and cons

Osmond diverted thousands of diapers from landfill.

Elsewhere in Canada there are efforts to promote reusables: several Quebec municipalities now offer cloth diaper subsidies, aiming to win over more parents.

But that doesn't mean cloth is the clear environmental winner overall in the diaper debate.

Cotton, the most popular source material for cloth diapers, requires immense amounts of water and chemicals to produce. Schwarcz estimated cotton soaks up 25 per cent of the world's insecticide use despite being grown on just three per cent of its arable land.

Then there is the laundry issue. It can take a lot to get a cloth diaper clean — hot water cycles, sometimes in duplicate for the heaviest soiled loads — not to mention the amount of time the absorbent pads require in a dryer.

One exhaustive study by the British government considered all those concerns and concluded that disposables diapers (or nappies, in British parlance) beat out cloth by a hair.

But that conclusion comes with a big asterisk.

"It is consumers' behaviour after purchase that determines most of the impacts from reusable nappies," the study stated, adding cloth can trump disposables if they are washed in water temperature at 60 C or less, are air dried and are used on a second child.

Schwarcz said by laundering mindfully, cloth beats disposable, "but it's not a landslide victory."

"If I were to put all of this together, my answer would be to use the cloth at home and disposables when travelling."

Compost and recycling

But there is another way, one Schwarcz sees as better suited to the hygienic standards required in daycare centres and nursing homes: recycling disposables.

The industry is in its infancy in Canada, but the City of Toronto has been turning parts of disposable diapers into compost since 2002.

Dirty disposables are collected curbside with other organic waste and brought to a processing facility, where all the organics are put into "basically a giant washing machine," said Nadine Kerr, a manager with the city's solid waste management services.

That washing machine separates plastics from organics; the plastics float to the top and are raked off then sent to landfill, while the organic materials — including baby poop — are sent on to anaerobic digesters, which create compost.

Each year, the city's facilities — which Kerr confirmed "definitely" smell inside — process 12,000 tonnes of baby and adult diapers, along with used menstrual products.

"The idea was to get as much diverted from landfill as we could," said Kerr.

Toronto may be doing more with disposables than most other Canadian municipalities — although check out these Calgary dads offering a similar service — but some overseas innovators are taking it a notch further.

Private companies in the U.K., like Knowaste and NappiCycle, now recycle all parts of disposables, even the plastics.

"Certainly it's doable," said Schwarcz. "The question is whether or not it is economically feasible."

But as Canadian demographics continue to skew older, Schwarcz said that economic question may soon become moot.

"There is a driving force for this because, of course the, population is increasing, especially the older population — and they use a lot of these incontinence products," he said.

"The best thing would be if these recycling facilities become commonplace."

Join the discussion on the CBC Waves of Change Facebook group, or email us: wavesofchange@cbc.ca.