How the Spanish flu compares to COVID-19: Lessons learned, answers still being pursued

'Each outbreak is its own thing, in its own context. People are really having to figure it out as they go'

The learned experiences from a devastating flu pandemic 100 years ago that staggered the world don't make it any easier this time around, says a historian and author who specializes in health and infectious disease.

While there are many similarities between how society is responding to COVID-19 and how it reacted to the Spanish flu of 1918-19, "there isn't a playbook," said Esyllt Jones, a professor of history at the University of Manitoba.

A century ago, health professionals faced an organism they didn't know a lot about. The same holds true now.

COVID-19 and the Spanish flu both presented novel, or new, viruses — which means there are no treatments, no vaccines, and no one has been exposed before so there is no immunity, said Jones, author of the book Influenza 1918: Disease, Death, and Struggle in Winnipeg.

"Each outbreak is its own thing, in its own context, and there's a lot about COVID-19 that's completely unique. So people are really having to figure it out as they go."

There is some greater scientific understanding now than in 1918, when viruses had not even been isolated yet, Jones said.

"But there is this underlying sense of not really knowing how the disease is behaving exactly."

That results in confusion for people about which messages they need to listen to. There have been, for example, mixed messages about the benefits of masks and whether someone without symptoms should wear one.

Still others have resorted to thinking it's just a bad cold and officials are overreacting, or that the pandemic is worse somewhere else and not a big concern locally.

That was the same thought in 1918.

In the late spring, as allied troops in Europe were battling the German army, word began to reach Canada that another invader was killing soldiers. A deadly flu was raging through the battlefields, causing fever and fatigue, pounding headaches and sore throats, before filling the lungs with fluid and choking the breath from its victims.

The flu started earlier in the year but the warring countries, not wanting to give information to the enemy, suppressed the news. Spain was a neutral country in the First World War, so the first uncensored news about the flu came from there, leading to the name.

Manitobans were initially shocked but not fearful — after all, Europe was an ocean away. If the flu did reach Canada's shores, Manitoba was thousands of kilometres from any major port. There was a sense of immunity.

That came to a sudden end in the fall.

The flu arrived in Canada on the same ships that brought troops home. It then made its way across the country by rail, reaching Winnipeg in late September.

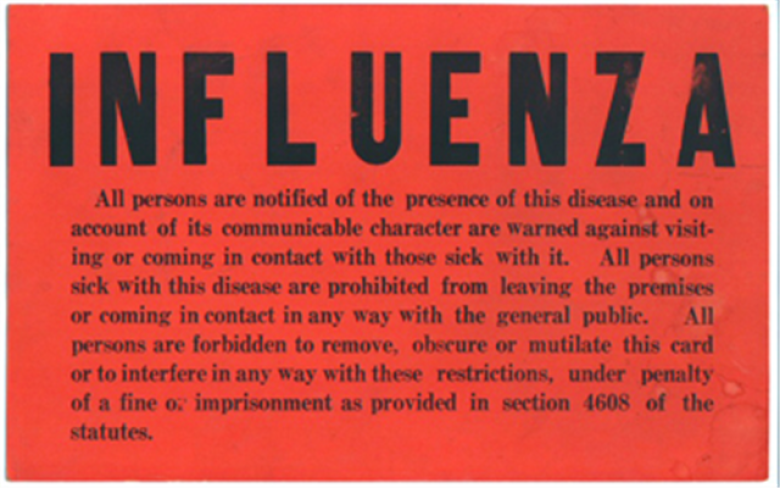

As the death toll mounted, Winnipeggers faced long bouts of isolation in an effort to rein in the spread.

Churches and schools, along with entertainment venues such as movie theatres, billiard halls, dance halls, and public bathhouses, were shuttered.

Gatherings were banned and limits put on how many people could be on streetcars or in grocery stores.

Hospital visiting hours were abolished and personal care homes were closed to all visitors.

People were urged to wash and a no-spitting bylaw was enforced for the first time in years.

Quarantine wards were set up in hospitals, and makeshift hospitals were created in available buildings as the regular facilities filled up.

A familiar story

Flash forward to 2019 and the story is much the same.

News surfaced in December about a flu outbreak in Wuhan, China. As cases mounted, it swept into Italy, Iran, and South Korea.

Still, many people in Canada continued, unfazed, with regular plans — including travel. There was a sense of being cautious but not overly worried, even as the first death from the illness in Canada was reported March 9 in British Columbia.

Two days later, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, pointing to 118,000 cases in 110 countries and territories, and thousands of deaths.

From that point, the dominoes fell. Professional sports leagues cancelled their seasons and major events began to follow suit. Bans on gatherings led to schools, churches, cafes, shops, parks, playgrounds, and non-essential businesses being closed.

Many of those broad measures echo 1918-19, but there are some significant differences as well, Jones said.

"The main one being the closure of workplaces. In 1918-19 people continued to go to work every day if they could and probably often even when they couldn't. They shouldn't have been there when they were ill," she said.

"Nobody seemed to take seriously the possibility that you would close down major sectors of the economy."

People forced themselves to go to work, for fear of losing their jobs and to make money so they could get treatment for family members who were ill. There was no universal health care and there were few unions.

"So that is very different now, as is the government's willingness in Canada to economically support people during these times," Jones said.

"So there have been some things that have fed into the response we're seeing now."

Another difference between 1918-19 and 2020 is that the global health system now crucial to the COVID-19 response did not exist a century ago, points out Michael Bresalier, a lecturer at Swansea University in the United Kingdom.

An expert in the history of disease — and a friend of Jones — Bresalier posted an article on the website History and Policy, noting the World Health Organization was not founded until 1948.

So nothing existed during the Spanish flu to advise governments, help them align their approaches, or facilitate the sharing of vital information and resources. Countries were left to piece together their own approaches.

An estimated one-third of the world's population was infected with the Spanish flu, resulting in at a death toll estimated to have been at least 50 million, but possibly twice that. Government reporting was poor and there were many people who refused to see a doctor for fear of the stigma attached to having the virus.

Some deaths were recorded only by church parishes, not public health officials. And in some countries, no reporting was done at all.

One in six Canadians contracted the infection and some 55,000 died. In Winnipeg, there were more than 1,200 deaths out of a population of 183,000.

The numbers for COVID-19 continue to climb across the world, but as of April 10, more than 1.6 million cases had been reported in 185 countries and territories, resulting in over 98,000 deaths, according to data from Johns Hopkins University.

More than 21,000 cases had been confirmed in Canada as of April 10, with more than 540 deaths.

A challenge that surfaced in 1918, and could again, is maintaining the strategies to slow the spread of the virus as the isolation drags on, said Jones.

During the Spanish flu, "the public health officer in Winnipeg faced a lot of pressure to end the closures because they were affecting the local economy in certain ways and they were certainly disrupting everyday life," she said.

That officer has to negotiate a deluge of messages from the federal government and provincial government, the best scientific practices, the state of the public mindset, and pressure from the business sector, Jones said.

That pressure mounts when the number of new cases starts falling.

Jones understands the impulse to get back to normal, to think things aren't so bad, when that happens.

But a drop in new cases doesn't necessarily mean the virus has weakened — it often means the measures put in place by government and health officials are working.

That makes it difficult for people understand the disease is still extremely dangerous.

"We just have to keep repeating the message," Jones said. "I'm always reminded that with the [Spanish] flu pandemic there were measures that could have been taken that weren't."

People also need to remember that beyond the battlefield, the Spanish flu hit the world in three waves.

The first, in spring of 1918, was generally mild and resulted in few deaths, The second, in the fall, was highly contagious and arrived with a vengeance. It led to death within just a few days, sometimes within hours, of someone showing symptoms.

The third wave occurred during the winter and into the spring of 1919, and was more lethal than the first, but less so than the second.

By summer of 1919, the pandemic nearly vanished — not because it was cured, but because those infected died or developed immunity.

Even then, some places in Canada experienced pockets of it into 1920, Jones said.

"So it really does become the question: Is that what this is going to look like and how can we plan for that? All of that is a big unknown for us now and unknowns are not comfortable for anyone," she said.

"On the bright side, everyone working in public health right now is learning every day about the disease and ideally, they're buying time, [so] should the disease return in a more serious way … they will have more tools in their tool box."