Fowler questions Canada's Afghan mission

West not investing the 'blood or treasure' to get work done

Retired Canadian diplomat Robert Fowler says the four months he spent in captivity with a band of al-Qaeda militants has fortified his critical view of Canada's role in Afghanistan — that the time and money would be better spent elsewhere.

"I cannot object to the objective in Afghanistan, but I just don't think in the West that we are prepared to invest the blood or treasure to get this done," says Fowler, a veteran diplomat who was in Niger as a UN Special Envoy when he was captured last December.

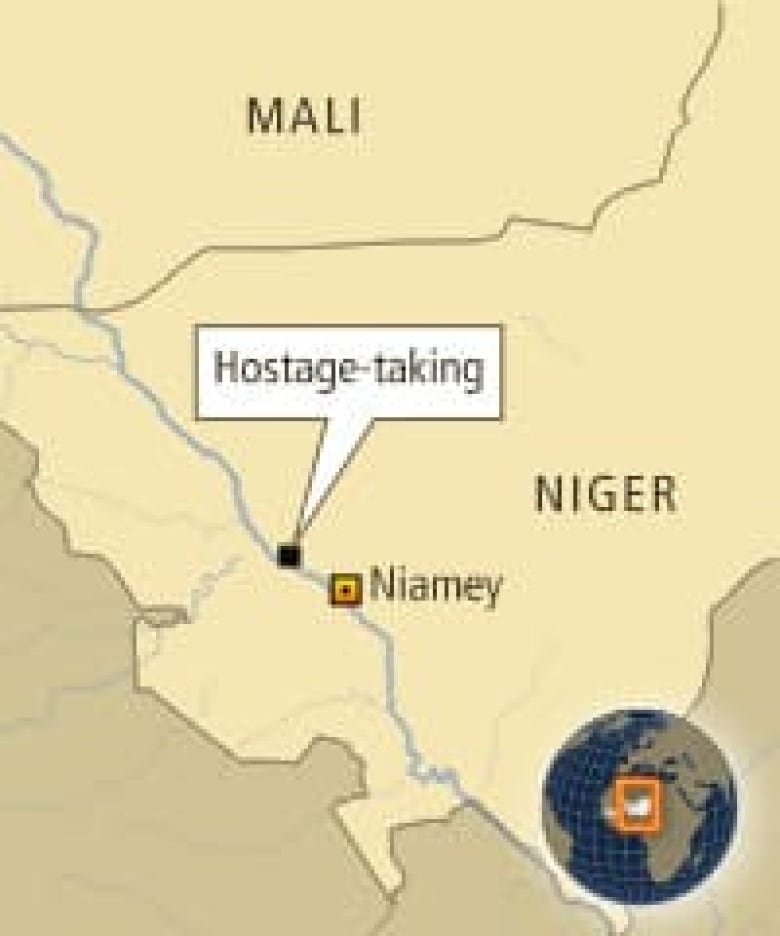

In an exclusive interview with CBC chief correspondent Peter Mansbridge on The National, Fowler revealed details of his harrowing 130 days in captivity after he and assistant, Louis Guay, were abducted northwest of Niger's capital, Niamey.

"It strikes me as rather extreme that one goes out and looks for particularly complex misery to fix," Fowler said about Canada's mission in Afghanistan. "There's lots of things to fix that can be done more efficiently and probably more effectively."

Fowler spent 38 years as a public servant and diplomat, serving as foreign policy adviser to former prime ministers Pierre Trudeau, John Turner and Brian Mulroney, before retiring in 2006. He was Canada's longest-serving ambassador to the United Nations, and worked on issues such as blood diamonds in Angola and the humanitarian crisis in Darfur.

Watch CBC's The National Wednesday night for more on Robert Fowler's story, including his emotional phone call home to his wife while he was being held captive.

Though a "noble objective," Fowler describes the Afghan mission as one of the most "complex, challenging" missions.

Canada's combat role in Afghanistan is scheduled to end in 2011, after nearly a decade of military involvement in the war-torn nation wracked by Taliban and al-Qaeda insurgencies. The Canadian military's death toll continues to rise, hitting 129 on Sunday with the deaths of two soldiers.

"It's not just the commitment and the wasting of our youth and the enormous, enormous cost in difficult financial times. It's to get it done, we will have to do some unpleasant things. I mean some deeply hard, this isn't — this is not a nice war."

No love, no joy in al-Qaeda camp

During their time in captivity, Fowler and Guay were given a remarkable glimpse into the lives of their captors, al-Qaeda's North African wing, the Algeria-based al-Qaeda Organization in the Islamic Maghreb, or AQIM.

The two were held at gunpoint by a group of about 20 men and children, ranging in age from seven years old to 60, as they moved from location to location to evade detection. Fowler says they were never tortured and their captors always maintained their distance.

"They live in a world that I can't understand," said Fowler. "There was no fun, there was no love, there was no joy."

"The only time I saw real excitement," says Fowler, was when a "new hot DVD" was delivered to the group from central al-Qaeda.

It was played during one of the regular "movie nights" — when the captors would prop a laptop on a pile of three spare tires so the group could view propaganda videos of blowing up American soldiers and convoys in Iraq and Afghanistan.

"Lots of suicide bombers crashing through gates blowing up some buildings … and every time this would happen the audience would scream.

"I eventually refused to go to TV night," said Fowler. "I said I had seen the twin towers come down 400 times. I don't need to see them again."

17 days of camel

Fowler and Guay spent most of their time in transit, sleeping or sitting in a catatonic state in the 50 C heat of the sub-Saharan environment.

The men survived largely on pasta and rice but ate meat, such as goat or sheep, on occasion. Once, their captors caught a camel, which provided meals for the group for 17 days.

"They'd immediately dry it and hang strips on the trees and in that climate, it would dry instantly," says Fowler. "It was actually pretty good. Mind you, any meat was pretty good. We knew that we desperately needed protein and we just weren't getting it."

Though water was plentiful, it was not always drinkable after being pulled from desert wells in filthy containers, some stamped with skull-and-crossbones danger symbols.

By the time Fowler and Guay were released on April 22, along with two European tourists, the retired diplomat had lost nearly 40 pounds, suffered a fractured vertebra from the 56-hour bumpy drive right after their capture and lost a tooth.

Ransom still unclear

Fowler wouldn't speak to ongoing speculation about whether a ransom was paid for his release.

He says he doesn't know what behind-the-scenes negotiations led to his safe trip home, but acknowledges, "I mean, they got something. I don't know from whom or how."

"Prime Minister Harper has said very clearly that Canada paid no ransom. I have absolutely no reason to believe he was misstating the fact."

His captors at one time demanded 20 of its members be freed in exchange for the hostages.

'Hope was weak'

The most heart-wrenching moment for the Canadians came on Day 85 when the captors granted them a phone call to their wives — a strategic move by the al-Qaeda wing to mobilize support back home.

After a 19-hour drive to a sand dune near the Algerian border, the two trekked to the top of the razorback dune to tap into the Algerian cell network for the phone call.

It was a frustrating experience as the men encountered answering machines, a dead battery and a quickly depleted credit line on the phones. But eventually, they got through.

"Then I was getting into the goodbyes and [my wife Mary] gave me hell. She said, 'What do you mean goodbye? You're coming home. We've got lots of things to do. Don't give up, don't be silly.'"

Throughout it all, Fowler struggled at times to keep spirits high.

"I never felt confident this will work out well," he says. "There were days when hope was weak …deeply depressing moments.

"But no, I never gave up hope."