Seattle man's conviction for 1987 murders of B.C.'s Tanya van Cuylenborg and Jay Cook overturned

Washington state court reverses conviction due to juror bias; William Talbott had been given 2 life sentences

The double murder conviction of a Seattle-area man found guilty in the cold-case homicide of a young B.C. couple has been overturned due to juror bias.

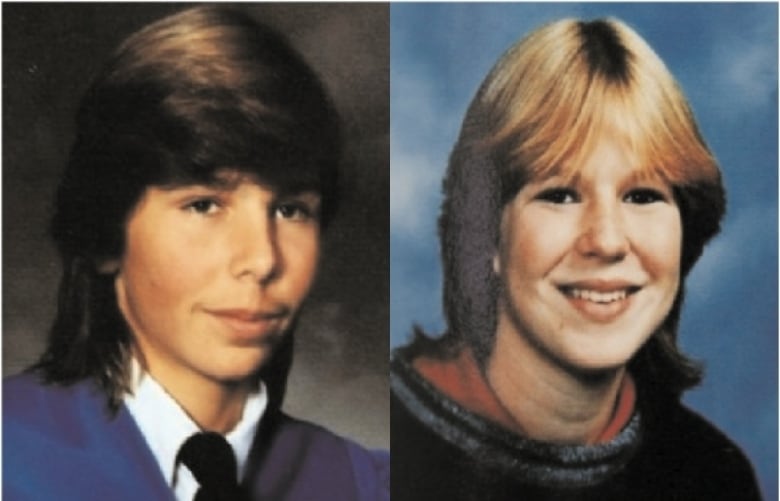

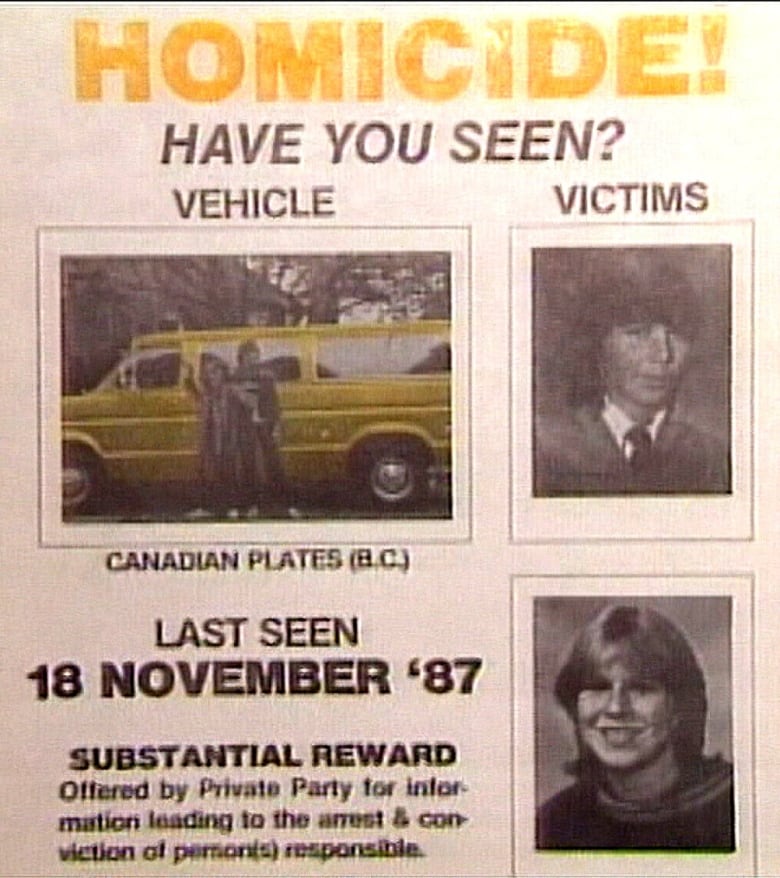

William Earl Talbott was arrested in 2018 on the strength of DNA genetic genealogy tracing, 31 years after the bodies of Tanya van Cuylenborg, 18, and Jay Cook, 20, both of Saanich, B.C., were found in northern Washington state.

Genetic genealogy involves identifying suspects by entering crime-scene DNA profiles into public databases that people have used for years to fill out their family trees.

In 2019, Talbott was found guilty by a jury of two counts of aggravated murder in the first degree and given two life sentences, which he appealed on the grounds that his right to an impartial jury was violated because a biased juror deliberated his case.

In a decision handed down Monday, the Division 1 Court of Appeals in Washington state said a woman identified as Juror 40 exhibited "actual bias" during her comments in voir dire. A voir dire is a legal procedure in which the admissibility of evidence and jurors is discussed.

According to the transcript, Juror 40 told both the state and defence her mother had experienced "a lot of domestic abuse." When asked if that would affect her ability to be fair and impartial she replied:

"To be honest, I — feel like I wouldn't know until the time came. But I also have a daughter, and I think that might also play a part in how I might feel. If there was some action taken toward a young woman, I might take that personally and not be able to be impartial."

The juror was then asked by the state if she would be able to set her personal experiences aside, including her mother's history of domestic abuse and her experience of being a mother, in favour of listening to the evidence in Talbott's trial.

"I could try ... I can't guarantee anything, right?," the juror said. "It's something I usually express with my husband, that there's always multiple sides to a story, and I'm a fact-based person, so I could tell you that I will give it my very best, should I end up being on the jury, to do that."

In the court's decision, the judges noted the case's similarity to other successful appeals where jurors provided "equivocal" or ambiguous responses when asked about whether they were biased before sitting as part of the jury.

They go on to say that they "cannot conclude that juror 40 was sufficiently [free of bias] such that Talbott was provided a fair and impartial jury."

This ended up being the reason the appellate court reversed Talbott's conviction. His attorneys raised many other issues related to the evidence in the case, as did Talbott in court papers he prepared himself. The appeals court only addressed juror bias, not concerns related to genetic genealogy.

Prosecutors have until Jan. 5 to ask the state Supreme Court to review the appeals court ruling.

First to be convicted due to DNA evidence

Talbott was the first ever person to be convicted as a result of genealogy research. Police in Washington state used information from public genealogy websites to pinpoint him as a suspect, then arrested him after getting a DNA sample from a cup that fell from his vehicle.

Cook and Van Cuylenborg were travelling from Saanich, B.C., to Seattle for an overnight trip in November 1987 when they disappeared.

Van Cuylenborg's body was found down an embankment in rural Skagit County, north of Seattle. She had been shot in the back of the head.

Cook's body was found two days later near a bridge over the Snoqualmie River in Monroe, Wash. He had been beaten with rocks and strangled.

No arrest was made in the case for more than 30 years. Talbott was eventually taken into custody after a DNA test came back as a positive match to DNA collected from the crime scene.

Experts from Parabon NanoLabs in Virginia were able to identify Talbott's great grandparents and family tree using public genealogy databases. They then worked forward to identify Talbott himself.

Police subsequently obtained a DNA sample from the cup Talbott had used to make the positive identification.

Juror 40 heard witness testimony for weeks and reached Talbott's initial guilty verdict with 11 others, following three days of deliberation.

With files from Karin Larsen, Akshay Kulkarni, The Associated Press, and Ronna Syed