50 years later: From Uganda to Canada, the exile that changed the course of a country

As refugees come from Ukraine, those from the largest non-European mass settlement here share advice

There's the sound of gunshots firing outside, accompanied by the crunch of gravel under the heavy wheels of military trucks — then, stillness, as lights go out in the early evening for curfew.

Salim and Laila Ahmed's memories of 50 years ago are shared by 60,000 refugees who experienced the trauma of banishment after dictator Idi Amin declared he would create what he called a "pure Uganda," a country whose only citizens were Black like himself.

The Ahmeds were among the Asian Ugandans expelled from the East African country in 1972, and can recall the pain of having just 90 days to leave their home, business and country barely a year after they married.

At first, Salim said he could not truly believe such a senseless decree.

"When everybody was leaving, we thought that we did not have to leave. I thought we'd be fine; we wouldn't have to go," Salim said.

Salim knew Amin as a customer at his grocery store — and he recalls attending the dictator's liberation dinner, never thinking he would one day kick him and his community members from their homes.

"My blood boils," Salim said in a recent interview. "I personally thought probably it was temporary, it would change, there was hope. But, it never did," he said.

He bought a return ticket, but never used it.

Largest non-European mass settlement

Many of the Ahmeds' memories, once tucked deep, are floating to the surface as they commemorate 50 years since their arrival in Vancouver — two of the roughly 7,000 Asian Ugandans who settled in Canada during this country's first non-European mass settlement.

Sikhs, Goans, Ismailis, Pakistanis, and more came to Canada from Uganda as refugees in the months following the expulsion order, fleeing violence at the hands of Amin's military.

For Ismaili Muslims like the Ahmeds, they reached Canada in part due to their spiritual leader, His Highness the Aga Khan, and his relationship with then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau.

They arrived on Oct. 24, 1972, with just 30 pounds each in their pockets. After a stranger took them in the moment they landed, they knew they'd found a safe place to call home.

Though overjoyed with the life they have built, the couple will never forget the hardship of their earliest days here. Successful shop owners in Uganda, in Canada they had to first accept odd jobs including shovelling snow and watering people's plants, all for as little as 10 cents an hour.

"I would do three jobs together … just to make ends meet," Laila said.

And the pain of their expulsion is never really really gone.

"My heart is still beating very hard because … Laila and I used to find people you're talking to one day [and] the next day they disappeared," Salim said.

'I was stateless'

Nazlin Rahemtulla was even younger than the Ahmeds when she left Uganda — she was 17.

She remembers exactly where she was when the announcement of the expulsion came: at her sister's wedding. None of the guests or family believed it.

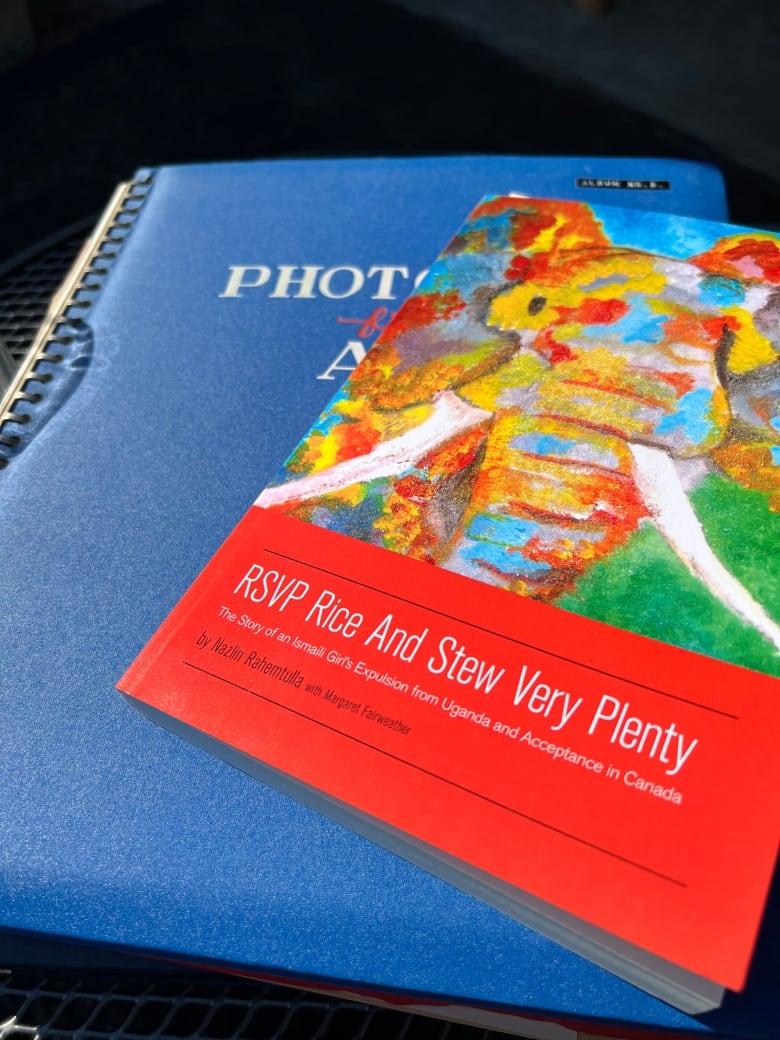

"I was a Ugandan citizen by virtue of my birth but, according to Amin's rules, I was stateless," she wrote in a book she's published about her experience.

When the expulsion became real, she left Uganda to go back to school in England, saying she was unsure she'd ever see her home again.

"I had convinced myself [my parents] would never make it out of Uganda alive, and my father had to wrench me away and force me in to the car," she said.

But they made it.

A country sunk in the past

She decided to return to Uganda in the '90s to reclaim her family's soft drink business and other property. But the family decided to leave the country behind them, selling everything.

"The country had sunk, I think they say, 60 years behind time. Why would anybody want to go back?" she said. "There's no reason to want to go back."

Instead, Rahemtulla and her family spent the last five decades moving on from their past and building a new life in Canada.

Rahemtulla lives with her siblings and nieces in a blended house in Vancouver just like she did in Uganda; she paints, she writes and she says this is the only home she needs. But, while reflecting on the past, the feelings are still complicated, she says.

"I don't think you ever heal … you learn to cope with it. Some memories fade, some will stay," Nazlin said.

"I just hope in some way I can pay this forward in some manner to other people, other immigrants who are coming to this country."

Flight to freedom

In 1972, some countries initially tried to refuse entrance to the Ugandan refugees.

But Canada not only welcomed thousands, it was one of the few places that sent pilots to get people out.

Tom Moul's father, Capt. Gordon Moul, was one of the Canadian pilots who volunteered to fly planes full of refugees out of Entebbe, a city roughly 35 kilometres southwest of Uganda's capital, Kampala.

On one of Moul's last flights out, things got scary and passengers were shot before even getting on board, his son said in an interview.

"People's lives were on the line," Moul said of the flight. "He got to the runway and put all his years of experience to play … the airplane didn't take off so much as the runway finished — and they kept going."

Capt. Gordon Moul received a citation of bravery from former prime minister Stephen Harper in 2013 for his role in the evacuation. The pilot died three years ago.

Making Canada a better place

The refugees Moul brought to Canada may have faced hardship in starting over, but they have shared countless stories of how they have thrived. They have worked to settle newcomers here, started charities and tried to make their new home a better place than it was when they arrived.

"We were very, very fortunate that we got a new life in Canada, and the Canadian government gave us the opportunity to come back and restart again," Salim said. "For that, we are ever so thankful and grateful for this country."

Of course, with thanks, comes a sense of sadness as they have seen new waves of refugees arrive — from Syria, Afghanistan and, recently, Ukraine, and more.

But Salim and others in his community say that Canada gave them a chance 50 years ago, changing the course of this country, and he believes the subsequent rounds of newcomers will do the same.

"Everyday in our morning and evening prayers, we say a special prayer for all the refugees and migrant workers. Because, you know, when you see that, it's very, very painful — we are very fortunate we got this opportunity."

He just wants those refugees and migrants to hold on to one piece of advice he cherishes himself: "What Canada has done for you, neither you, your children, or grandchildren will ever be able to repay it. Make sure you can be the best you can be."