Survivor speaks out as B.C. pledges $100M to address historical wrongs of interning Japanese Canadians

90% of Japanese Canadians in B.C. were detained and stripped of their homes, possessions during WW II

B.C. Premier John Horgan committed a $100 million endowment Saturday to address the lasting effects of the internment of Japanese Canadians in the province during the Second World War.

Horgan made the announcement on Saturday from the Steveston Martial Arts Centre, the oldest Japanese-style dojo in North America, in Richmond B.C.

It comes on the 80th anniversary of the first arrivals of Japanese Canadians to the Greenwood, Kaslo, New Denver, Slocan City, and Sandon Internment Camps in 1942.

"This endowment will not change the past, but it will ensure that generations that are with us still, and those that come after, will have the opportunity to see something positive coming out of what was clearly a very, very dark period in our collective histories,'' Horgan said at the Saturday news conference.

The province said in a news release more than 90 per cent of Japanese Canadians in B.C. were detained and stripped of their homes, possessions, and businesses during the Second World War.

The endowment, which will be provided through the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC), will support health and wellness programs for internment-era survivors, restoration of heritage sites, the creation of a monument to honour survivors, and updating the province's school curriculum to reflect this history.

President of the NAJC Lorene Oikawa said at Saturday's announcement approximately 22,000 Japanese Canadians were forcibly uprooted in B.C.

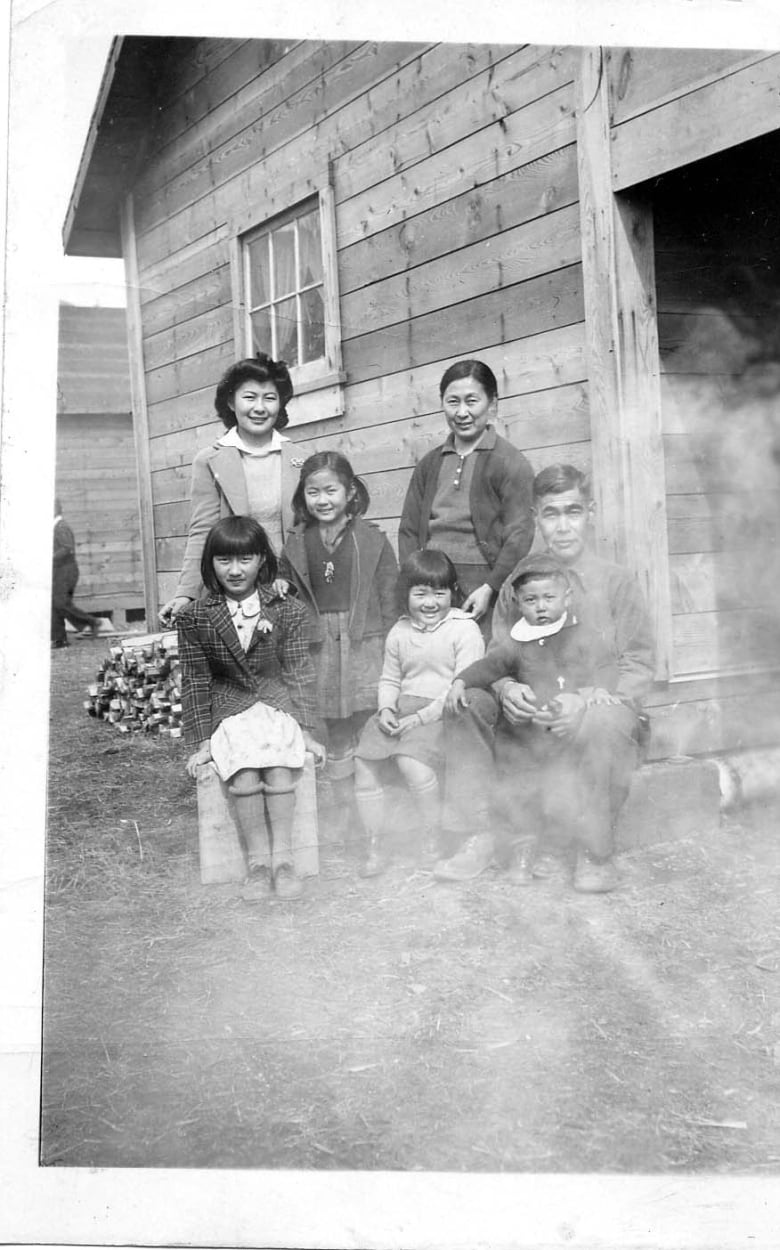

"They had nothing, and they had to start over. And they did. This is very personal, this is my family. It's your families," said Oikawa.

The province says the funding builds on a government apology for the wrongs made in the B.C. Legislature in 2012 and responds to a redress proposal advanced in 2021 by the NAJC.

'Legalized theft'

The province says around 6,000 people who were interned are alive today. One of them, 87-year-old internment camp survivor Keiko Mary Kitagawa, spoke at Saturday's announcement.

Kitagawa, who was born on Salt Spring Island, said her family and people in her community lost their fishing boats, farms, businesses, homes, personal items, and vehicles, among much else.

"It was legalized theft," said Kitagawa.

The memories of her father being taken away by the RCMP in 1942, when she was only seven years old, came flooding back.

"All the suffering kept coming back to me. . . that's a trauma that I cannot get rid of," said Kitagawa.

After six months of physical labour doing road work, Kitagawa's dad was given the option to reunite with his family – but on the condition that they move to Alberta to work on a sugar beet farm.

"Sugar beet farming is like slavery really. It was hard work and we lived in this tiny shack, not fit for humans really," said Kitagawa.

Their entire family, including the children and retired grandparents, were forced to work farming sugar beets.

The family was moved around to different internment camps in Alberta and B.C. until 1949 when the government granted Japanese Canadians their freedom.

"Many like my grandparents lost their enjoyment of a retirement, for which they worked a whole lifetime to achieve," said Kitagawa. "Many like my parents lost the most productive years of their lives."

With files from Janella Hamilton and The Canadian Press