We explain how Canada reports air pollution and what it means for your health

Experts agree AQHI is useful but has limitations

Health officials in British Columbia and beyond are demystifying what the air quality health index (AQHI) means as much of B.C. is still choked by wildfire smoke.

The AQHI is an online health information communication tool, developed by Health Canada, which reflects the severity of air pollution and how it can affect both the general population and at-risk populations, such as seniors, infants and people with heart or lung conditions in the short-term.

The AQHI takes the real-time levels of three pollutants commonly found in Canadian air — fine particulate matter, ground-level ozone and nitrogen dioxide — and runs them through a complex calculation.

The provinces publish the numbers online within their respective jurisdictions.

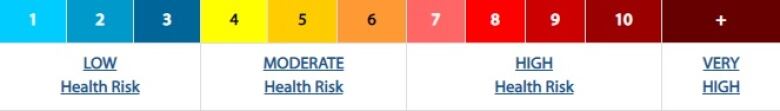

The result of the AQHI calculation is a number from one to 10 and "10+."

Confusion has arisen when, on occasion, AQHI numbers exceed 10. For example, during the 2017 B.C. wildfires, some extremely high numbers were published: Williams Lake hit 36. Kamloops hit a staggering 49.

FYI: While we breathe easier as the <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/AirQuality?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#AirQuality</a> advisory lifts for <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/MetroVancouver?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#MetroVancouver</a> and central <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/FraserValley?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#FraserValley</a>, this is what <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/Kamloops?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#Kamloops</a> looked like today. Video from <a href="https://twitter.com/DHerbertCBC?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@DHerbertCBC</a>. <a href="https://twitter.com/cbcnewsbc?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@cbcnewsbc</a> <a href="https://twitter.com/CBCVancouver?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">@CBCVancouver</a> <a href="https://twitter.com/hashtag/BCWildfire?src=hash&ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw">#BCWildfire</a> <a href="https://t.co/t6ZLgHa0KC">pic.twitter.com/t6ZLgHa0KC</a>

—@DanBurrittWhat do the numbers mean?

According to Dr. Dave Stieb, a Vancouver-based public health doctor with Health Canada, and one of the developers of the index, each number on the scale from one to 10 represents the percentage increase in mortality risk due to pollution.

"We're pretty confident that when you move from a five to a 10 on the scale, the risk to health doubles," Stieb said. "But moving from a 10 to a 20, we're not as confident.

"The slope of the line sort of levels off, for whatever reason."

For that reason, the scale is capped at 10. The scale also includes the figure of "10+" which represents an unquantifiable risk.

Last year, some readers may recall hearing numbers far above 10, published during the 2017 B.C. wildfires

In Smithers, B.C. Ministry of Environment meteorologist Ben Weinstein said that was simply a glitch in the AQHI reporting software that was fixed this year.

"Some of these concentrations we saw last year and again this year are new extremes," Weinstein explained. "I think the magnitude kind of took everybody by surprise."

He said because the health advice doesn't change beyond 10, there's little point to reporting higher numbers.

Limitations

Researchers generally agree the AQHI is a useful tool for reporting public health concerns to Canadians but it has limitations.

Weinstein said the index uses uses three common urban pollutants, which can make it challenging to accurately report concerns in rural communities.

"In a lot of rural communities where particulate matter [from smoke] is the main pollutant, the air quality health index sometimes ranks low even though particulate matter concentrations are quite high," he said.

In those areas, or where other pollutants are found (such as industrial Trail, where the B.C. Lung Association found the province's highest levels of sulfur dioxide) special plans are developed, he said.

McMaster University associate professor Dr. Sally Radisic says her 2012 research, in Hamilton, found only 21 per cent of people at risk were using AQHI info to plan their days — less than the general population.

"It's a great tool but it's really dependent on the user," Radisic said. "The individual has to sort of self-identify at what level the AQHI is having an adverse impact on his or her health."

Public Health Ontario's chief of environmental health, Dr. Ray Copes, said the AQHI can't tell people the long-term risks of air pollution where they are, since it only measures short-term mortality risks.

Long-term pollution exposure, he said, is a far greater health concern for most.

"What works in reducing risks for air pollution is to reduce the amount of pollution in the air we breathe," Copes said.